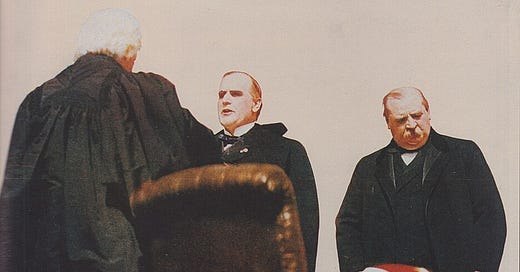

Last week, in Chapter 24, we dealt with Presidential inaugural addresses. Some of these have been memorable. One which decidedly was not was the first inaugural address of our 25th President, William McKinley (1843 – 1901), delivered on March 4, 1897. One passage, however, is worth remembering. McKinley declared, “We want no wars of conquest; we must avoid the temptation of territorial aggression. War should never be entered upon until every agency of peace has failed. . . .” 1 Thirteen months later, McKinley asked for and received from Congress a declaration of war against Spain.

In February of the following year (i.e., 1899), the United States went to war against the Philippines. This war was not declared. It was far bloodier than the war against Spain. When McKinley delivered his inaugural address, few Americans had ever heard of the Philippines. According to one source, only 35 articles had appeared about them in American magazines in the eight decades prior to 1898.2 Few Americans knew what they were, and fewer knew where they were. The American annexation of the Philippines “marked a major historical departure for the American republic, a breach in their traditions and a shock to their established values.”3 McKinley’s inaugural address did not offer the slightest hint that this was in the offering.

Why bring this up now?

Because President-elect Donald Trump has elevated McKinley to prominence after a well-deserved slumber of a century and a quarter. Trump wants to change the name of the tallest mountain in America. This mountain was originally named Mount McKinley. However, in 2015, the Obama administration renamed it Mount Denali.4 (Has any other President’s name ever been removed from a mountain?). Trump wants the name McKinley restored.

The name McKinley was given to the mountain in 1896, a couple of months before McKinley was elected president. The man who named it was a gold prospector, William Andrews Dickey (1862 – 1939). “We named our great peak Mount McKinley, after William McKinley of Ohio, who has been nominated for the Presidency, . . .” Dickey proudly explained.5 Like McKinley, Dickey favored the gold standard rather than bimetallism (a system which makes silver as well as gold legal tender). Silver was the major issue in the election of 1896.6

In 1975, the state of Alaska requested that the name of the mountain be changed from McKinley to Denali. The name “Denali” is from the language of Alaskan natives and means “high” or “tall.”7 For decades, the Ohio congressional delegation was united in its opposition to this change. McKinley was a representative from Ohio and also the governor of the state. He is buried in his hometown of Canton. Despite this opposition, the Obama administration managed to push the name change through.8 In 2015 when the change was announced, Trump, then a candidate for the Presidency for the first time, tweeted that the name change was a “great insult to Ohio.”9 He promised that he would return the mountain’s name to McKinley. He spent four years in the White House, and the mountain is still Denali.

Why, you may ask, does Trump want to change the name back to McKinley? With the world in flames, why devote a nanosecond to this project? His interest has been ignited by his desire to gain control of the Panama Canal. This is a bit circuitous, but here it goes.

Trump has asserted, “We’re being ripped off at the Panama Canal. . . . A secure Panama Canal is crucial. . . . We built it. We’re the ones who use it. They gave it away. . . .” (The antecedent of “they” is not provided.) “Our Navy and commerce have been treated in an unfair and injudicious way. . . . They haven’t treated us fairly. . . .” Unless there is a change, “we will demand that the Panama Canal be returned to the United States in full, quickly and without question.”10

McKinley comes into Trump’s narrative because Trump believes that McKinley made America so wealthy through high tariffs that the country was able to afford building the Panama Canal. The canal was actually built by Theodore Roosevelt, McKinley’s successor; but according to Trump, McKinley deserves much, if not most, of the credit because of how wealthy he made America. That wealth was generated by McKinley’s devotion to tariffs.

McKinley, Trump believes, “was a very good, maybe a great president. They took his name off Mount McKinley. That’s what they do to people.” (Once again, who “they” might be is not mentioned.) Trump described McKinley as a “very great businessman. . . A very successful businessman.” In short, McKinley was a great man. “That’s one of the reasons we are going to bring back the name of Mount McKinley because I think he deserves it.”11

It is the combination of these two factors – the enriching of America through tariffs and the construction of the Panama Canal – that has caused the hummingbird of Trump’s mind to alight on William McKinley.

In addition to a belief in tariffs, Trump and McKinley have something else in common. They (were) are both imperialists. Trump is talking about acquiring Greenland, making Canada the 51st state, and of course acquiring the Panama Canal.12 For McKinley’s part, during his administration the United States acquired its first overseas territories including Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Samoa, Guam, and the Philippines. Unlike Trump, McKinley did not campaign on an imperialistic platform; but that was the result.

Trump talks endlessly about tariffs. “I consider that tariff to be the most beautiful word in the dictionary.”13 An allegiance to high tariffs is the most consistent strain in the in the career of McKinley. He was “the Napoleon of protection [i.e., of tariff protection].”14 “It was said he could make a tariff schedule read like poetry, and he developed an effectively simple manner of presentation that impressed even hostile audiences.”15 The McKinley tariff of 1890 (McKinley was a congressman at the time) raised rates. Indeed, they raised rates even higher than McKinley himself wanted. But tariffs are often the result of compromises. Asked why he accepted such high rates, McKinley said “for the best reason in the world, to get my bill passed. My idea was to get the act through Congress, and to make the necessary reductions later. I realized that some things were too high, but I couldn’t get my bill through without it.”16

Not long after his inauguration as President, McKinley signed the Dingley tariff into law on July 24, 1897. This provided the protection on which McKinley had campaigned. The Dingley tariff was the highest tariff in American history, and it was the law of the land for a dozen years. It was the longest lived tariff in the nation’s history.17

Trump sees himself as similar to McKinley in these two areas. High tariffs and imperialism.

That said, Trump obviously does not know very much about McKinley. After serving courageously in the Civil War, McKinley became a lawyer and was a lifelong politician. He was never a businessman. In the words of a biographer, “He knew little of business. It did not interest him. . . .”18 As far as McKinley’s rank among Presidents is concerned, there are endless surveys of this issue. For what it may be worth, McKinley is never ranked among the great or near-great Presidents. Neither is he a cellar dweller with the worst. He often finds himself in the second quartile.19 Interestingly, he does not rank highly among the Presidents whom the public remembers. He is something of a forgotten man. One survey places him at number 28, bracketed by Warren Harding and John Tyler. Another places him at 36, behind Tyler but above Millard Fillmore.20 Trump’s references to him recently may result in his ranking more highly in the future.

In personal relationships, McKinley and Trump are polar opposites. McKinley was honest and decent. He cared deeply for his wife, who suffered from epilepsy and severe depression. The depression was brought on by the deaths of her two daughters, one aged four years and one only four months. Through all her trials, McKinley remained utterly devoted to his wife. He spent hours by her side almost every day. “He was a private man of relatively modest personal means. . . . He was the last American president whose demeanor and values would now be called Victorian. He was soberly dressed, very concerned for the proprieties of public appearance and behavior, religious, dignified, and virtuous,”21 The opposite of Trump on every dimension.

Weighed against McKinley’s admirable personal qualities is the fact that his conduct of foreign affairs was costly indeed. As one scholar has asked, “Why, in a war to end years of bloody fighting and devastation in nearby Cuba, did the United States end up becoming the ruler of the faraway Philippine Islands? True, the Filipinos, like the nearby Cubans, had also rebelled against Spanish rule. But hardly anyone in the United States had noticed or cared.”22

John Hay (1838 – 1905), the American Secretary of State from 1898 to 1905, famously described the Spanish-American War as the “splendid little war.”23 The United States declared war on Spain on April 21, 1898. The war officially ended with the Peace of Paris signed on December 10, 1898. The American death toll was 2,446. Of this number a staggering 2,061 men died from disease rather than from fighting.24

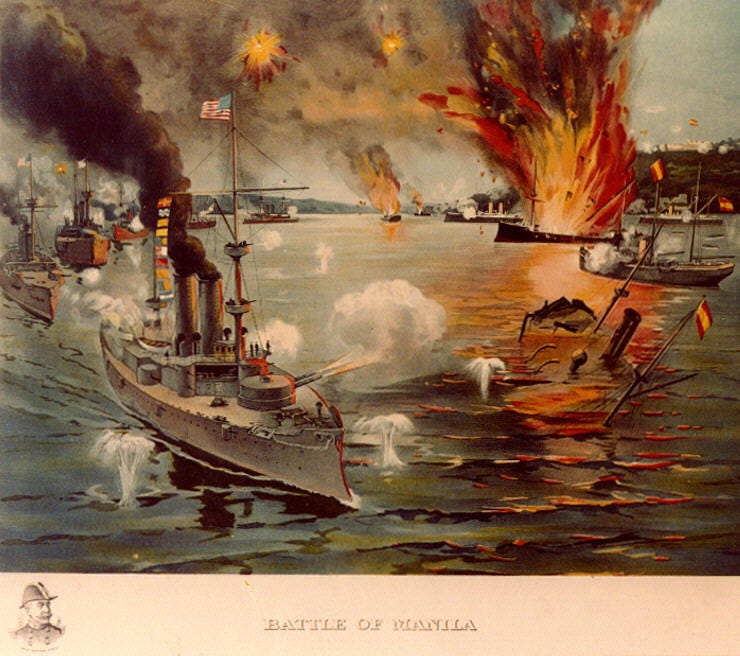

As soon as war was declared, Commodore George Dewey (1837 – 1917) was ordered to sail the American naval squadron based in Hong Kong to Manila, capital of the Philippines, and engage the Spanish fleet there. He won a startlingly easy victory on May 1, sinking the antiquated Spanish fleet with no loss of American life. Following that event, the United States step-by-step found itself deciding to take control of the whole Philippine archipelago with its 7.7 million inhabitants, equal to a tenth of the population of the United States. No one called the violence which followed this decision a “splendid little war.” It was a bloody campaign with its share of atrocities, lasting officially from 1899 to 1902 but actually dragging on until 1913.25

How did this come to pass? McKinley, was ultimately responsible for this ill advised decision. Neither by experience nor by intellect was he equipped to deal with this issue. As he said, “If old Dewey had just sailed away when he smashed the Spanish fleet, what a lot of trouble he would have saved us.”26

As a result of Dewey’s victory, McKinley fell into what one scholar has called “the meddler’s trap.”27 After Dewey’s victory, McKinley came to conceptualize the Philippine issue in terms of whether the United States should abandon a territory once it had acquired it. That is, he felt the issue was whether or not the American flag, once raised, should be taken down. Had “old Dewey” not sailed into Manila, the issue would have been whether the flag should be raised there. The answer to that would have been no.

McKinley’s style of leadership “was not charismatic . . . His was another kind of leadership – that of a judge.”28 Unfortunately, the situation he faced called for more than merely selecting among alternatives presented to him by advisors. The decision called for a man who could reconceptualize the whole situation. McKinley was not that man. He drifted into this decision when what was needed was a policy characterized by mastery.

Is there a lesson for today in this story? The lesson is that it is vital, especially in foreign affairs when by the nature of things decision makers are operating with limited knowledge, to think long and hard before taking the first step. Time and again, in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and also in the Philippines, it has proven easier to start something than to stop it.

Before Dewey sailed to Manila, a vital question was not answered. What is the endgame? Indeed, the question was not asked. The decision made itself. In his first inaugural address, McKinley said he did not want a war of conquest. Yet that is what he wound up getting the United States into. As a result, many Americans and thousands more Filipinos lost their lives.

As Donald Trump meanderers around the world, he appears not to be asking the endgame question. That should give us all pause.

Should Mount Denali revert to Mount McKinley? Your opinion is as good as mine.

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/mckin1.asp

Richard Hofstadter, “Cuba, The Philippines, and Manifest Destiny” in The Paranoid Style in American Politics (New York: Vintage, 2008) p. 199.

Hofstadter, “Philippines,” p. 177.

https://web.archive.org/web/20181008012637/https:/www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/elips/documents/3337%20-%20Changing%20the%20Name%20of%20Mount%20McKinley%20to%20Denali.pdf

Bill Sherwood, ed., Dinali: A Literary Anthology (Seattle: Mountaineers Books, 2000) p. 59.

The best book on this remarkable election is: R. Hal Williams, Realigning America (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2010).

“Trump wants to change the name of Denali back to Mount McKinley,” Anchorage Daily News, December 23, 2024.

See Note # 4.

https://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/252380-trump-pledges-to-reverse-obamas-mountain-renaming/

www.youtube.com/watch?v=XuIeXJw6BA8&t=1664s

See Note # 10.

For a good discussion on France 24, see www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDuIpXRycJ4&t=1328s

1. See Note # 10. Trump has said this often.

1. John Authers, “What Trump doesn't get about McKinley and tariffs,” Bloomberg, July 19, 2024.

H. Wayne Morgan, William McKinley and His America (Kent, O: Kent State University Press, 2003) p. 83.

Morgan, McKinley, p. 184.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dingley_Act

Morgan, McKinley, p. 572.

See, for example, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_rankings_of_presidents_of_the_United_States

See Note # 19.

Philip Zelikow, “Why Did America Cross the Pacific? Reconstructing the U.S. Decision to Take the Philippines, 1898-99,” Texas National Security Review, Vol. 1, Iss 1 (November, 2017) p. 6.

Zelikow, “Why,” p. 5.

https://dp.la/exhibitions/american-empire/age-imperialism/splendid-little-war

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish–American_War

David J. Silbey, A War of Empire and Frontier (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007) p. 225.

Zelikow, “Why,” p. 13.

Aroop Mukharji, “The Meddler’s Trap,” International Security, Vol. 48, No. 2 (Fall, 2023) pp. 49 – 90.

Zelikow, “Why,” pp. 16-17.