Germany instituted a democratic form of government from its defeat in World War I in 1918 until the Nazi seizure of power in 1933. Germany’s first experiment in democracy – known as the Weimar Republic – failed. History has proven that a democracy can die. Do we in the United States today have anything to learn from democracy’s demise in Germany? At first glance, the answer would appear to be no because Germany’s history and the circumstances under which its democracy came to grief are so different from America’s reality today.

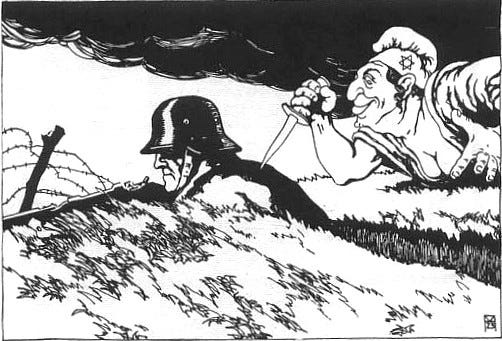

The roots of democracy in Germany were shallow, and the Weimar experiment was launched upon a very stormy sea. By late 1918, Germany was thoroughly beaten militarily and economically in World War I. However, the country was not actually invaded. For that reason and a number of others, Germans were allowed to believe that their country had been “stabbed in the back” by its political left-wing—meaning socialists and communists – and also by Jews.1 The peace treaty which Germany was forced to sign at Versailles was blamed not on the people who made the war, traditional monarchists of the Bismarckian Second Reich, but rather on the Republicans who succeeded them. Hitler was to call them “the November criminals of 1918.”2 The treaty cost Germany 13% of its territory and a tenth of its population.3 It saddled the nation with enormous monetary reparations. And it included the “war guilt” “clause – Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles – which stipulated that “Germany accepts the responsibility” for starting World War I.4 The war guilt clause was an insult which intensified the injury caused by the defeat and the reparations Germany was forced to pay.

The stab in the back idea was untrue. And it was an an idea that did a lot of damage. One cannot find a more dramatic example of the importance of the historian’s task to communicate the truth than the comfortable fable of the stab in the back.

The new German Republic had to put down a revolt immediately. Political violence haunted the nation during the Weimar years. Adolf Hitler attempted a violent overthrow of the government in the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. This failed, and Hitler wound up in prison for eight months. He concluded that if the Nazis were to seize power, it would have to be done by legal means. He succeeded in doing so a decade later.

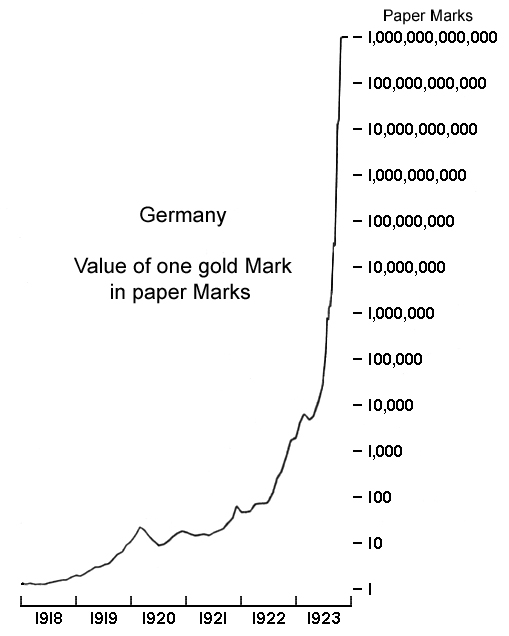

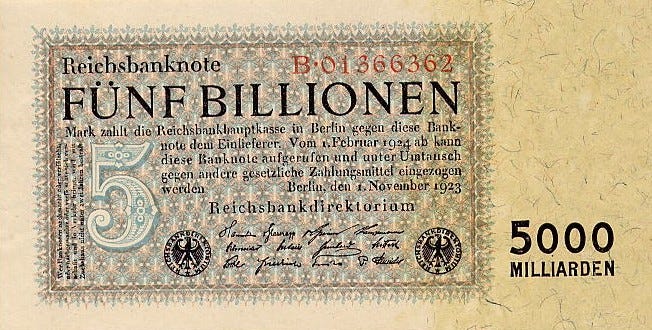

In addition to armed revolts, economic catastrophe of unimaginable seriousness also beset Weimar. In the early 1920s, hyperinflation stalked the land.

By way of illustration:

November, 1921 – 263RM (i.e., Reichsmarks) bought $1.

July, 1922 – 463RM bought $1

August, 1922 – over 1,000RM bought $1

October, 1922 – 3,000RM bought $1

December, 1922 – 7,000RM bought $1

January, 1923 – over 17,000RM bought $1

April, 1923 – 24,000RM bought $1

July, 1923 – 353,000RM bought $1

August, 1923 – 4,621,000RM bought $1

September, 1923 – 98,860,000RM bought $1

October, 1923 – 25,260,000,000RM bought $1

November, 1923 – 2,193,600,000,000RM bought $1

December, 1923 – 4,200,000,000,000RM bought $15

Hyperinflation was “terrifying. Money lost its meaning almost completely. . . . A kilo of rye bread . . . cost 163 marks on 3 January 1923, more than 10 times that amount in July . . . , and 233 billion marks” on November 19. “Unable to afford the most basic necessities, crowds began to riot and loot food shops. Gunfights broke out between gangs of miners. . . . Malnutrition caused an immediate rise in deaths from tuberculosis. . . . Germany was grinding to a halt.”6

A “combination of astute political moves and clever financial reforms” saved the day.7 However, the impact of such a catastrophe on the citizenry can scarcely be overstated. “It added to the feeling in the more conservative sections of the population of a world turned upside down, first by defeat, then by revolution, and now by economics.”8

The Nazi Party had in Hitler a man of cunning, utter ruthlessness, and remarkable charisma, especially in front of crowds. He understood that the way to destroy the Weimar Republic and thus undermine German democracy was from inside the government rather than outside it. And this is precisely what he proceeded to do, maneuvering himself into the office of Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

Prior to this, in the late 1920s, the Weimar Republic was relatively peaceful. The achievements of Weimar culture have been justly celebrated.9 It would take another event with the impact of the hyperinflation for a fanatic like Hitler and his radical, violent followers to come to power. That event was the Great Depression.

The Great Depression was a blow from which an already weakened political system could not recover. The Nazis did not offer a specific roadmap to rescue Germany from its economic collapse. But the very vagueness of the Nazi project was transformed into an asset. People “could read into it what they wanted and edit out” what they wanted to ignore.10 Although the name of the Nazis is short for National Socialist German Workers Party, it was not a political party in the usual sense of that word. It was a movement, and one that substituted “race” for “class” in its discussion of Germany’s past and its future.11 It was the obsession with race which led to the emphasis on the blood of the people, the purity of which had to be guarded.

When at last Hitler gained power, it became clear that this was not an ordinary change in government. As one German observed, “[E]veryone could have fallen into everyone else’s arms in the name of Hitler. Intoxication without wine.”12 That last observation was an apt metaphor. Another person observed that she favored Hitler not because of any specifics but because his only program was Germany.13

Alongside nurturing such sentiments, the Nazis “unleashed a campaign of political violence and terror that dwarfed anything so far.”14 Dachau, the first German concentration camp, was opened in 1933 for left-wing opponents of the new regime. Fighting Nazism in Germany meant risking your life and very often losing it.

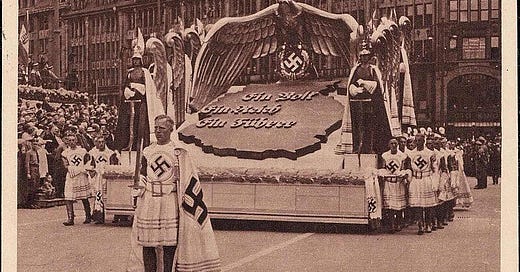

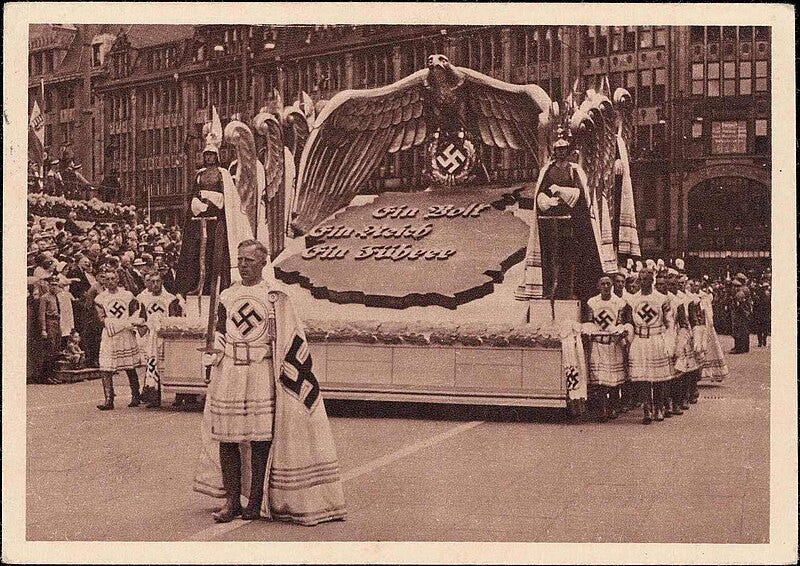

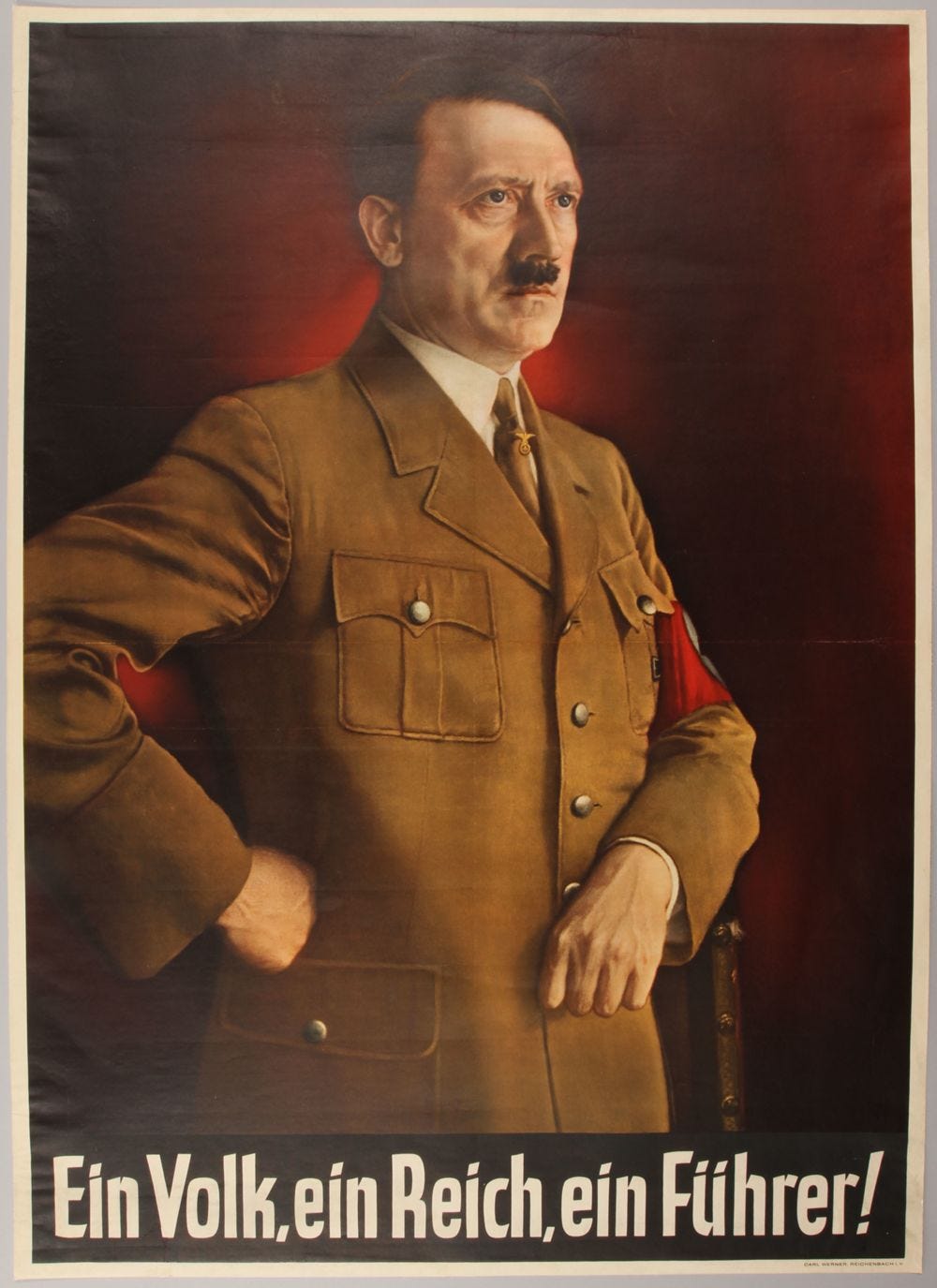

Ein Volk. Ein Reich, Ein Fūrhrer. One people. One nation (or realm). One leader. That was what was on offer, and that is what replaced the multi-party democracy of the Weimar years from 1918 to 1933. And that was the path that led Germany and the world to carnage and moral squalor.

It goes without saying that Hitler is one of the monsters of human history. Nevertheless, our incoming president Donald Trump has had some nice things to say about him. According to Marine Corps General John Kelley, Trump’s chief of staff, Trump asked, “Why can’t you be like the German generals?” When informed that Hitler’s generals tried to assassinate him, Trump responded “No, no, no. They were totally loyal to him.” Hitler “did some good things,” Trump insisted.15

Trump has appropriated some of the language of the Nazis. He talks of immigrants “poisoning the blood of our country,”16 the kind of phrase that did not exist in the American political vocabulary prior to him.

Trump has also suggested that American democracy might be drawing to a close. Speaking to a Christian group on July 27, he said that if they voted for him, “[I]n four years, you won’t have to vote again. We’ll have fixed it so good you’re not gonna have to vote.”17

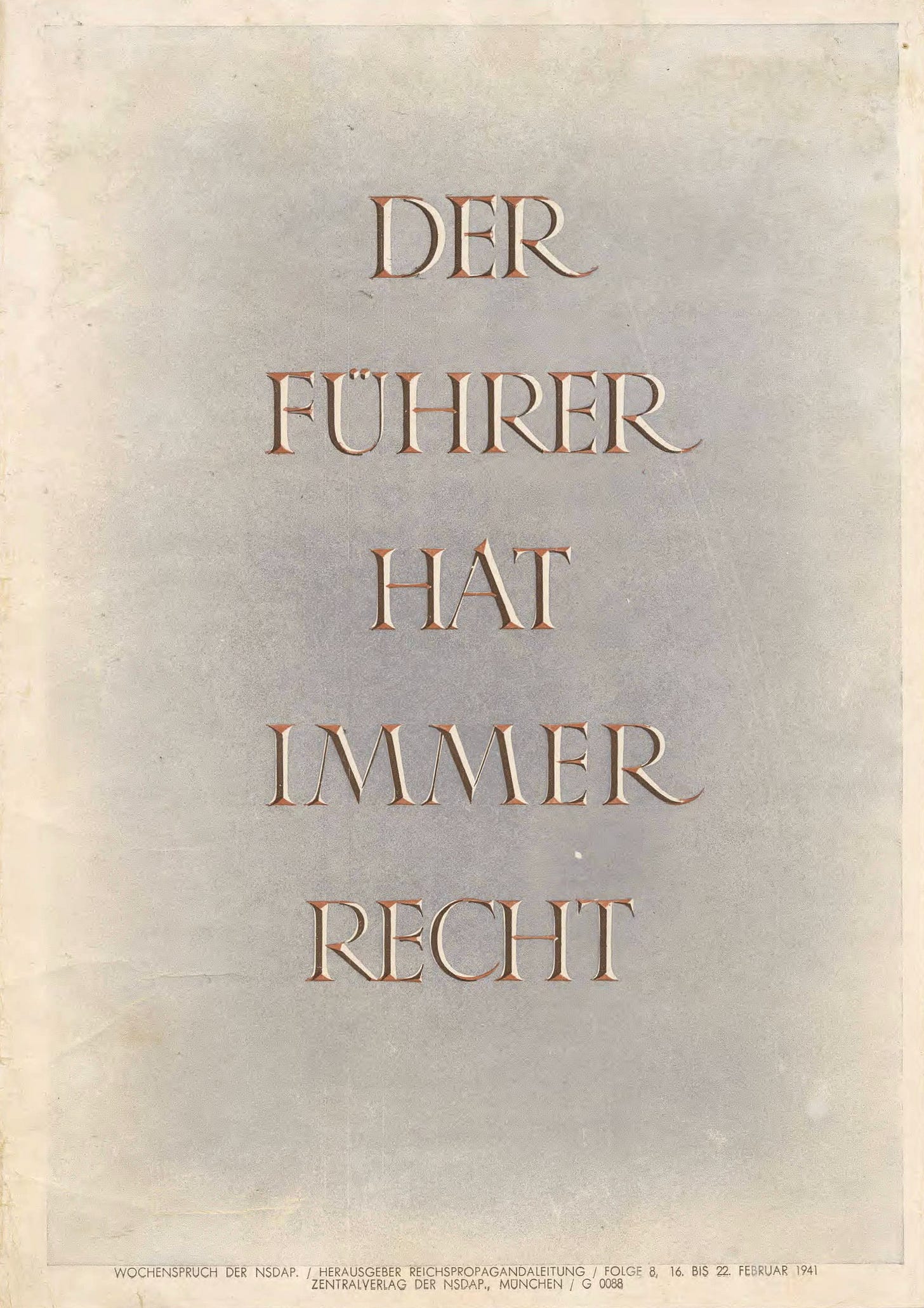

An election in Germany was scheduled for five weeks after Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933. According to historian Richard J. Evans, “Hitler and the leading Nazis were making it clear in their more unguarded moments that the coming election would be the last.”18

The first lesson the history of Germany’s attempt at democracy teaches is that loose talk about the sunset of democracy must be taken seriously and literally. Trump is guilty of this kind of talk. Hitler made similar comments in Germany, and the results are there for all to see.

The second lesson is the toxicity of what the Nazis called the “Führerprinzip,”or in English the “leadership principle.” This is the assertion that the leader is always right. Indeed, this is one of the hallmarks of fascism between the two world wars. In Italy, it was Mussolini, il duce. In Spain, it was Franco, el caudillo. Blind obedience to a leader who is supposedly always right has consistently resulted in disaster.

Do we have an American version of the leadership principle in Donald Trump? This is not a ridiculous question.

The third lesson is the danger of charisma. Hitler exercised it as few other people in world history have. Trump also is a charismatic man. Charisma is seductive. And it is very difficult for standard politics to deal with the charismatic figure. One Trump supporter said that she backed him because he “loves America.” Recall the German who experienced Hitler as intoxication without wine. It is extraordinarily difficult for normal politicians to cope with this appeal. However, it is also true that without at least a touch of charisma, politicians cannot transform themselves into effective agents of change. A politician with no touch of charisma, like Joe Biden, bores people to death and invites the creation of his opposite.

Democracy can die even if it is rooted firmly in a nation’s history. It can die even without such shocks as hyperinflation and depression. We may be about to witness this phenomenon in our own country beginning on January 20.

The United States is in a very odd place right now. It is similar to the time between the conquest of Poland in 1939 and the invasion of the west in 1940. The Phony War. We all know “something wicked this way comes,”19 but we don’t know precisely what it is going to be. And nothing terrible is happening in the United States this moment. Suspended animation.

Most of the information in this post dealing with Germany from 1871 to 1933 is taken from the outstanding book by Sir Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin, 2005). For this observation, see, for example, p. 272.

Evans, Reich, p. 353.

Evans, Reich, p. 62.

https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1919Parisv13/ch17subch1#:~:text=The%20Allied%20and%20Associated%20Governments,aggression%20of%20Germany%20and%20her

Evans, Reich, pp. 104-105.

Evans, Reich, pp. 106-107.

Evans, Reich, p. 108.

Evans, Reich, p. 112.

See especially, Peter Gay, Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider (New York: Norton, 1968). “It is the tragedy of the Weimar Republic that . . . the trauma of its birth was so severe that it could never enlist the wholehearted loyalty of all, or even many, of it beneficiaries.” p. 23.

Evans, Reich, p. 265.

Evans, Reich, p. 173.

Evans, Reich, p. 311.

Evans, Reich, p. 324.

Evans, Reich, p. 317.

Jeffrey Goldberg, “Trump: ‘I Need the Kind of Generals Hitler Had,’” The Atlantic, October 22, 2024.

https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/trump-says-immigrants-are-poisoning-blood-country-biden-campaign-liken-rcna130141

https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-tells-christians-they-wont-have-vote-after-this-election-2024-07-27/

Evans, Reich, p. 323.

William Shakespeare, “Macbeth,” Act 4, Scene 1.