Chapter 22: Richard Nixon and Donald Trump

A Tale of Two Presidencies

Fifty years ago, President Richard Nixon was forced to resign in disgrace because of the Watergate scandal. No other President has ever suffered this fate. Key players in the Nixon drama were two reporters for the Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. This year, they published a Fiftieth Anniversary Edition of their classic book, All The President’s Men, which recounted the Watergate drama (or melodrama). Their introduction to this edition compares 1974 to 2024.1

They begin by citing George Washington’s Farewell address delivered in 1796, in which he warned, “Cunning, ambitious, and un-principled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people to usurp for themselves the reins of government.”2 Nixon and Trump, Woodward and Bernstein explain, “demonstrate the shocking genius of our first President’s foresight.”3

For 50 years, these two reporters studied Nixon; and they came to believe that the threat he posed to the United States was overcome once and for all. “[W]e believed with great conviction that never again would America have a President who would trample the national interest” and undermine democracy through “the audacious pursuit of personal and political self–interest.”4 Trump, they write, proved them wrong.

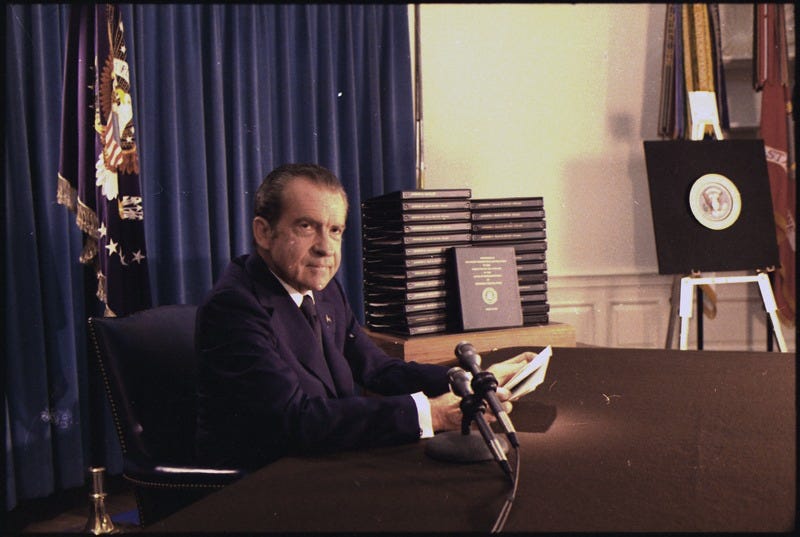

“Watergate” specifically refers to the break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in the Watergate office complex by people attached to Nixon’s re-election committee on June 17, 1972, and also to Nixon’s failed attempt to cover up his own involvement. On August 9, 1974, facing certain impeachment in the House of Representatives and conviction in the Senate, Nixon resigned; and the stain of his transgressions will never be washed away.

Considered alone, Watergate does look like a “third rate burglary,” as Nixon’s press secretary described it.5 However, the break-in was not an exception to Nixon’s Presidency, it was the essence of it. “[T]he Watergate break in was just another in a series of projects to help Nixon ‘get the goods’ on his opponents and try to destroy them. . . .”6 This was a routine Nixon operation.

In 1971, Nixon’s people targeted the man presumed to be the strongest candidate the Democrats could nominate for the Presidency in the election of 1972, Senator Edmund Muskie. Through a concerted campaign of dirty tricks, Muskie’s campaign was destroyed. The Democrats nominated George McGovern, a very fine man; but he never had a chance against the incumbent.

In the 1972 presidential election, Nixon won in a landslide of historic proportions, taking every state but Massachusetts and the District of Columbia (which obviously is not a state but does have three electoral votes). Needing 270 electoral votes to win, Nixon received 520 to McGovern’s 17. He took 60.7% of the popular vote, up from 43.2% in 1968.

No one knew it at the time, but Nixon’s second term was doomed before that election even took place. On February 16, 1971, a taping system was installed in the White House. Nixon figured the system would protect himself from others, but the tapes eventually destroyed him.

The so-called “smoking gun” tape proved that on June 23, 1972, less than a week after the Watergate break-in, Nixon knew all about it and devised to plan to cover it up.

For more than two years, Nixon insisted that he knew nothing of such things. Nixon and his team of toadies, many of whom wound up in jail, struggled to keep the contents of that tape secret. On May 17, 1973, a committee of the Senate empowered to investigate, Watergate began its nationally televised hearings. On July 13, it was learned that a taping system existed in the White House. On July 23, Nixon refused to turn over the tapes to the Senate Watergate Committee or to the special prosecutor on the grounds of national security and executive privilege. On May 9 of the following year, the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives began impeachment hearings. And on July 24, the Supreme Court unanimously demanded that Nixon hand over all his tapes to investigators.

The tapes were utterly devastating and not just because they proved Nixon had been lying to everyone for many months. They stripped him naked and revealed “the real man – mean, vindictive, panicky.”7 “Out came the profanity and the anti—Semitism, the rambling conversations and the clear impression that the White House was a den of suspicion, the court of the Borgias. . . .”8 In a word, the tapes revealed Nixon to be “an evil man.”9

The courts and Congress succeeded in separating Nixon from the White House because “a group of mostly ordinary men acted extraordinarily.”10 We were still “a government of laws and not of men.”11 But the system might have failed. This we know because up to now, in the era of Trump, the system has failed.

Nixon and Trump are different in many ways. At least until now, it is fair to say that Nixon is the worse of the two in that his immoral and failed Vietnam policy resulted in the deaths of untold numbers of people. But these two men are alike in that they both attempted to overthrow the government. As Woodward and Bernstein wrote referring to one of Trump’s enablers, Trump was presented with “a blueprint for a coup.”12

Trump had been preparing the nation for his coup for months before the election in November. He began attacking the legitimacy of the election as early as June and has never stopped down to the present day.

Nixon and Trump are similar also in that hatred is at the center of their universe. Nixon concluded his farewell to office on August 9, 1974 with the following bizarre observation. “Always remember, others may hate you – but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself.”13 Nixon indeed did hate the people who hated him, and he did destroy himself. Nevertheless, this is a passing strange statement to leave with the nation. It does not bear comparison to Washington’s Farewell.

But Nixon’s babbling was no more strange than Woodward interview with Trump on December 30, 2019. One of Trump’s assistants prepared a video of Democrats listening to Trump’s state of the union address. “The first shot was of Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who looked bored. Trump was watching over Woodward’s shoulder and was agitated. ‘They hate me,’ the President said. ‘You’re seeing hate!’ The camera stopped on Senator Elizabeth Warren. . . She was listening and had a bland, unemotional look on her face. ‘Hate!’ Trump said. A shot of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez . . . was next. She had no expression on her face. ‘Hate! See the hate!’ Trump said. The camera lingered a long time on Senator Kamala Harris.. . . . She had a bland, polite look on her face. ‘Hate!’ Trump said loudly within inches of Woodward’s neck. ‘See the hate! See the hate!’

“It was a remarkable moment,” recalled Woodward, who was deeply impressed by the intensity of Trump’s reaction to the images. “Many Democrats, of course, did hate him. . . . But this Trump spectacle was unforgettable and bizarre.”14

Both Trump and Nixon are (were) damaged men. No one is perfect, but their shortcomings are so acute that neither should have ever been in the White House. Trump returns to the Presidency next month. Why did he succeed while Nixon was crushed?

One can see the explanation in microcosm by looking at the Washington Post.

In 1974, the paper was owned by Katherine Graham. When Woodward and Bernstein’s stories were reported, she “was feeling beleaguered. The constant attacks on us by . . . people throughout the administration were effective and taking their toll. . . . [T]he pressures on the Post to cease and desist . . . were intense.”15 But she stayed the course and in the end was vindicated.

The current owner of the post, multi-billionaire Jeff Bezos, cancelled the paper’s forthcoming endorsement of Kamala Harris shortly before the 2024 election. The same day that this decision was handed down, candidate Trump met with executives of Bezos’s space company, Blue Origin. Bezos unconvincingly claimed that this was merely a coincidence.16 At any rate, the stark contrast between the courageous Katherine Graham and the cowardly Jeff Bezos is a sign of the times.

Look at Congress. In 1973, the Senate launched its Watergate investigation committee by a vote of 77 to 0. In 2021, the Senate failed to convict Donald Trump of the crimes for which the House had impeached him. That failure may prove to be the turning point in American history. If Trump had been convicted, he could not have run for office again; and the nation would be free of him at last.

Look at the Supreme Court. The Court voted unanimously in 1974 that Nixon had to turn over his tapes to investigators.17 It is difficult to conceive of the corrupt hacks on the Court of today doing anything to make Trump’s life difficult in the slightest.

Perhaps the biggest difference between 1974 and 2024 is the disposition of the American public. Nixon left office with no public support. Trump in striking contrast is a popular man. Trump succeeded in summoning a mob to ransack the capitol on January 6, 2021. If Nixon were to have summoned a mob, no one would have shown up.

It is possible that Trump’s popularity will decline as it becomes apparent that he does not have the ability – assuming he has the desire – to deliver for his loyal multitudes on the implicit and explicit promises he has made. If Trump should begin to lose the support of his followers, that is the time that our democracy will be in greatest peril. It is quite unclear what could prevent Trump from declaring martial law and cancelling the elections of 2026 or 2028.

It was claimed during the 2024 Presidential campaign that democracy was on the ballot. Democracy lost. Whether that loss will prove permanent, time will tell.

New York: Simon & Schuster, 2024.

For context, Washington wrote “[C]ombinations or associations. . . may now and then answer popular ends, [and] they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.” https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/Washingtons_Farewell_Address.pdf

Woodward and Bernstein, Men, p. 12.

Woodward and Bernstein, Men, p. 12.

Woodward and Bernstein, Men, p. 44.

Elizabeth Drew, Richard M. Nixon (New York: Henry Holt, 2007) p. 105.

Garry Wills, Nixon Agonistes (New York: Open Road, 2017) p. 16.

Drew, Nixon, p. 125.

Hunter S. Thompson, “He Was a Crook,” Atlantic, July, 1994, p. 6. This is essential.

Drew, Nixon, p. 123.

Drew, Nixon, p. 118.

Woodward and Bernstein, Men, p. 19.

Woodward and Bernstein, Men, p. 28.

Woodward and Bernstein, Men, p. 27.

Katherine Graham, Personal History (New York: Knopf, 2002) p. 665.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2024/10/28/jeff-bezos-washington-post-trust/

The vote was actually 8 to zero, rather than 9 to zero, because Associate Justice William Rehnquist recused himself. He had been an Assistant Attorney General in the Nixon Administration