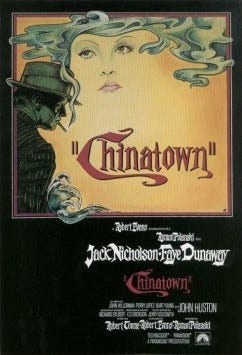

Chapter 27: Chinatown

Viewing the Motion Picture Today

“Chinatown” is a motion picture released on June 20, 1974. Like “The Godfather,” which was released two years earlier, “Chinatown” was perfect for the moment it hit the theatres. A month and a half later, Nixon was forced to resign because of the Watergate scandal. His White House was mired in corruption. In the film, it is the city of Los Angeles, and specifically water rights, that are corrupt. Indeed, one reviewer noted that Chinatown was Watergate with real water.1

In “Chinatown”, the action moves from misplaced self- assurance, to puzzlement, to catastrophe. The self assured male lead is a private detective named J. J. Gittes (played by Jack Nicholson). The female lead is Evelyn Mulwray (played by Faye Dunaway), a victim with something to hide. The monster hovering over the action is Noah Cross (played by John Huston).

“Chinatown” is a detective story which transcends its genre. It is about a man who keeps asking questions which were better left unanswered and who is possessed of a degree of self-confidence which is unwarranted. He is also a man who does not learn from his mistakes.

The viewer sees the action through Gittes’s eyes. He is hired by a woman claiming to be Evelyn Mulwray, the wife of Hollis Mulwray, the chief engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water. Gittes trails Hollis and discovers that he is spending time with an attractive young woman. Gittes assumes Holllis is having an affair, and the incriminating photographs that Gittes takes find their way into the Los Angeles newspapers.

The real Evelyn Mulwray then confronts Gittes, who is determined to get to the bottom of why he was hired by an impostor in the first place. What he eventually discovers is that Evelyn Mulwray’s father, Noah Cross, is planning on using control over the water of Los Angeles County to acquire land at depressed prices and vastly enrich himself.

The viewer comes to realize that Los Angeles as portrayed in this film is profoundly corrupt. A drought is purposely intensified by a scheme to divert water from reservoirs and dump it into the ocean, thus starving farmers off their land and facilitating the purchase of that land at a fraction of its real value. On a personal level, we learn that the wealthy, powerful Cross is not only greedy, he is deeply evil.

In the movie’s climactic scene, Gittes demands that Evelyn Mulwray tell him who the woman is whom he had supposed was her husband’s mistress. The following exchange ensues2:

GITTES

Who is she? And don't give me that crap about it being your sister.

You don't have a sister.

EVELYN

I'll tell you the truth...

GITTES

That's good. Now what's her name?

EVELYN

— Katherine.

GITTES

Katherine?... Katherine who?

EVELYN

— she's my daughter.

Gittes stares at her. He's been charged with anger and when

Evelyn says this it explodes. He hits her full in the face.

Evelyn stares back at him. The blow has forced tears from

her eyes, but she makes no move, not even to defend herself.

GITTES

I said the truth!

EVELYN

— she's my sister —

Gittes slaps her again.

EVELYN

(continuing)

— she's my daughter.

Gittes slaps her again.

EVELYN

(continuing)

— my sister.

He hits her again.

EVELYN

(continuing)

My daughter, my sister --

He belts her finally, knocking her into a cheap Chinese vase which shatters and she collapses on the sofa, sobbing.

GITTES

I said I want the truth.

EVELYN

(almost screaming it)

She's my sister and my daughter!

The truth finally comes out. It isn’t pretty. Evelyn concludes by saying: “—my father and I, understand, or is it too tough for you?”

At last, Gittes has the complete picture. Evelyn Mulwray was raped by her father, Noah Cross, when she was 15 years old. Not only did Cross want to control all the water in the Los Angeles basin, he wanted to control the girl, Katherine, who was both his daughter and his granddaughter.

“Chinatown” concludes with Evelyn trying to escape with Katherine, her sister and her daughter, from Los Angeles. Evelyn is shot dead in the attempt. Cross gets hold of the screaming Katherine. All this takes place outside the home of Evelyn’s butler. That home is in Chinatown. Jake tries to intervene to save Evelyn’s life but fails. The picture ends with one of Jake’s partners saying to him, "Forget It, Jake – it’s Chinatown.”

What does that mean?

Chinatown is “a metaphor for a moral climate of such Byzantine corruption that no man can fathom it.”3 The corruption is so complex that it is beyond comprehension. In the face of this complexity, the wise course of action is inaction because effort will only make matters worse.

Gittes understands this at some level. When Evelyn asks him about his life prior to becoming a private detective, he replies that he was “working for the district attorney.” In fact, he was on the police force. “Doing what?” Evelyn asks. “As little as possible,” Gittes replies. “The DA gives his man advice like that?” Evelyn asks. Gittes: “They do in Chinatown.”

Evelyn saw that Gittes did not want to talk about Chinatown. Gittes: “You can’t always tell what’s going on there. . . . I thought I was helping someone from getting hurt and actually I ended up making sure they were hurt.”

“The police,” as one reviewer noted, “cannot grapple with the enormity of public and private evil [the director Roman] Polanski tells us through the film’s terrifying climax set quite literally in Chinatown, because like Gittes and ourselves they are unable to grasp the profound perversities of the human heart. The failure of the forces of order is not one of will. . . but of imagination.”4

At the center of “the profound perversity of the human heart” is the figure of Noah Cross. There is a revealing exchange between Gittes and Cross as the madness at the center of this story is revealed to us:

GITTES

How much are you worth?

CROSS

I have no idea. How much do you want?

GITTES

I want to know what you're worth — over ten million?

CROSS

Oh, my, yes.

GITTES

Then why are you doing it? How much better can you eat? What can you buy that you can't already afford?

CROSS

The future, Mr. Gittes — the future.

Now where's the girl?...

I want the only daughter I have left... as you found out, Evelyn was lost to me a long time ago.

GITTES

Who do you blame for that? Her?

CROSS

I don't blame myself. You see, Mr. Gittes, most people never have to face the fact that at the right time and right place, they're capable of anything.

Gittes could not stop asking questions. But in Chinatown, it is important to do as little as possible and to ask as little as one can. The result of his inquisitiveness is precisely what had transpired previously. The person he was trying to help was hurt more severely than she would have been otherwise.

One article has compared “Chinatown” to “Oedipus Rex.” This is a bit of a stretch, but there are some remarkable similarities. Oedipus constantly asks questions, the answers to which it would have been better not to know. For his part, Jake describes himself as “just a snoop.” The Thebes of Oedipus is in the grip of a plague. The Los Angeles of Chinatown is in the grip of a drought. Perhaps most striking, incest plays a central role in both “Oedipus” and “Chinatown.”

But one need not go this far afield to appreciate the importance of “Chinatown” to our own world today. This motion picture asks us to think about what motivates people. The question is posed directly when Gittes asks Cross what motivates him. What can he buy that he cannot already afford? Cross answers: “The future.” Sitting at Donald Trump’s inaugural address on January 20 were three of the richest people in history: Musk, Bezos, and Zuckerberg. Is the future what they have in mind? It must be more than one more yacht, or rocket, or island.

What, at his advanced age, motivates Trump? He has always lusted after money. He now has more than he could ever have dreamt of. Is he competing for the future also? Yet he seems mired in the past. He is remarkably petty. He has cancelled the security arrangements for public servants who annoyed him. He still watches late night comedians and takes offense when they criticize him.

And what of the rest of us? Trump is the central political figure of our age. Wherever he goes, corruption follows. What nation are we living in? Is this the United States that we knew before Trump’s ride down that escalator in 2015? Or do we now live in our own version of Chinatown?

Or is that one more question than we should be asking?

Wayne D. McGinnis, “Chinatown: Roman Polanski’s Contemporary Oedipus Story,” Film Quarterly, 3 (3): (1975) 249–251.

This and all other quotations from the film are from: Robert Towne, “’Chinatown’ Screenplay” https://www.public.asu.edu/~srbeatty/394/Chinatown.pdf

Quoted in McGinnis, “Chinatown,” p. 249.

Quoted in McGinnis, “Chinatown,” p. 250.

I loved this post! I forgot what a great film Chinatown is. You've motivated me to watch it again. As for the theme of corruption, it's a sad commentary on the human condition that corruption seems unavoidable in human dealings with one another.

- was an interesting read indeed. During my college years in Dramaturgy at Istanbul University, we critically analyzed this film, deconstructing the scenario, acting, and the scenes. I never imagined then I would connect it to these days' context, but the entire class was in an awe with the readings. Critically, it was brutally true nonetheless normal, as we had become so accustomed to corruption. We were eager to deconstruct and not to rush into seemingly fitting solutions. I took a moment to pause and reread the post nostalgically. It is Chinatown. Thanks.

P.S. Of course, Oedipus was our holy bible back then and it still is.