The dictionary defines stereotype as a “mental picture . . . that represents an oversimplified opinion, prejudicial attitude, or uncritical judgement.”1 The word was endowed with this meaning by a journalist named Walter Lippmann (1889–1974) in his book Public Opinion, published in 1922.2 Stereotypes play an important role in how we perceive the world, so a discussion of what Lippmann meant by this word might shed light on how our nation has arrived in the situation in which we find ourselves today.

Here are some of Lippmann’s observations in Public Opinion about stereotypes:

Especially in wartime, people take “as fact, not what is, but what [they suppose] to be the fact.” 3

“ . . . [U]nder certain conditions, men respond as powerfully to fictions as they do to realities, and . . . in many cases they help to create the very fictions to which they respond.”4

A pseudo-environment is inserted between man and his actual environment. “To the pseudo-environment his behavior is a response. But because it is behavior, the consequences. . . operate not in the pseudo-environment where the behavior is stimulated but in the real environment where action eventuates.”5

“[W]hat each man does is based not on direct and certain knowledge, but on pictures made by himself or given to him.”6

Democracy “never seriously faced the problem which arises because the pictures inside people’s heads do not automatically correspond with the world outside.”7

“The world is vast, the situations that concern us are intricate, the messages are few, the biggest part of opinion must be constructed in the imagination.”8

“For the most part we do not first see, and then define, we define first and then see. In the great blooming, buzzing confusion of the outer world we pick out what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture.”9

“The systems of stereotypes may be the core of our personal tradition, the defenses of our position in society. They are an ordered, more or less consistent picture of the world, to which our habits, our tastes, our capacities, our comforts and our hopes have adjusted themselves.”10

“No wonder. . . that any disturbance of the stereotypes seems like an attack upon the foundations of the universe.”11

The hallmark of the perfect stereotype “is that it precedes the use of reason; is a form of perception, imposes a certain character on the data of our senses before the data reaches the intelligence. . . . There is nothing so obdurate to education or to criticism as the stereotype. It stamps itself upon the evidence in the very act of securing the evidence."12

What does all this mean? We distort reality because of our preconceived notions. Thus, we create a pseudo-environment. However, although our perceptions are formed in that pseudo-environment, we take actions in the real world. Our efforts are based upon incorrect perceptions. Moreover, interested parties generate propaganda which is designed further to distort our perceptions.

If these propositions are true, they constitute a devastating set of observations about the functioning of democracy. How can an educated electorate be supposed when the world perceived by the electorate is so far removed from reality? Lippmann’s statement of this problem is much more convincing than the solutions he offers.

To understand why Public Opinion was such a breakthrough book, we must place it in historical contact. Lippmann never would have written this book in 1917. What happened between 1917 and 1922 which generated such a pessimistic portrait of the world? In order to find out the answer to this question, we must supply historical context.

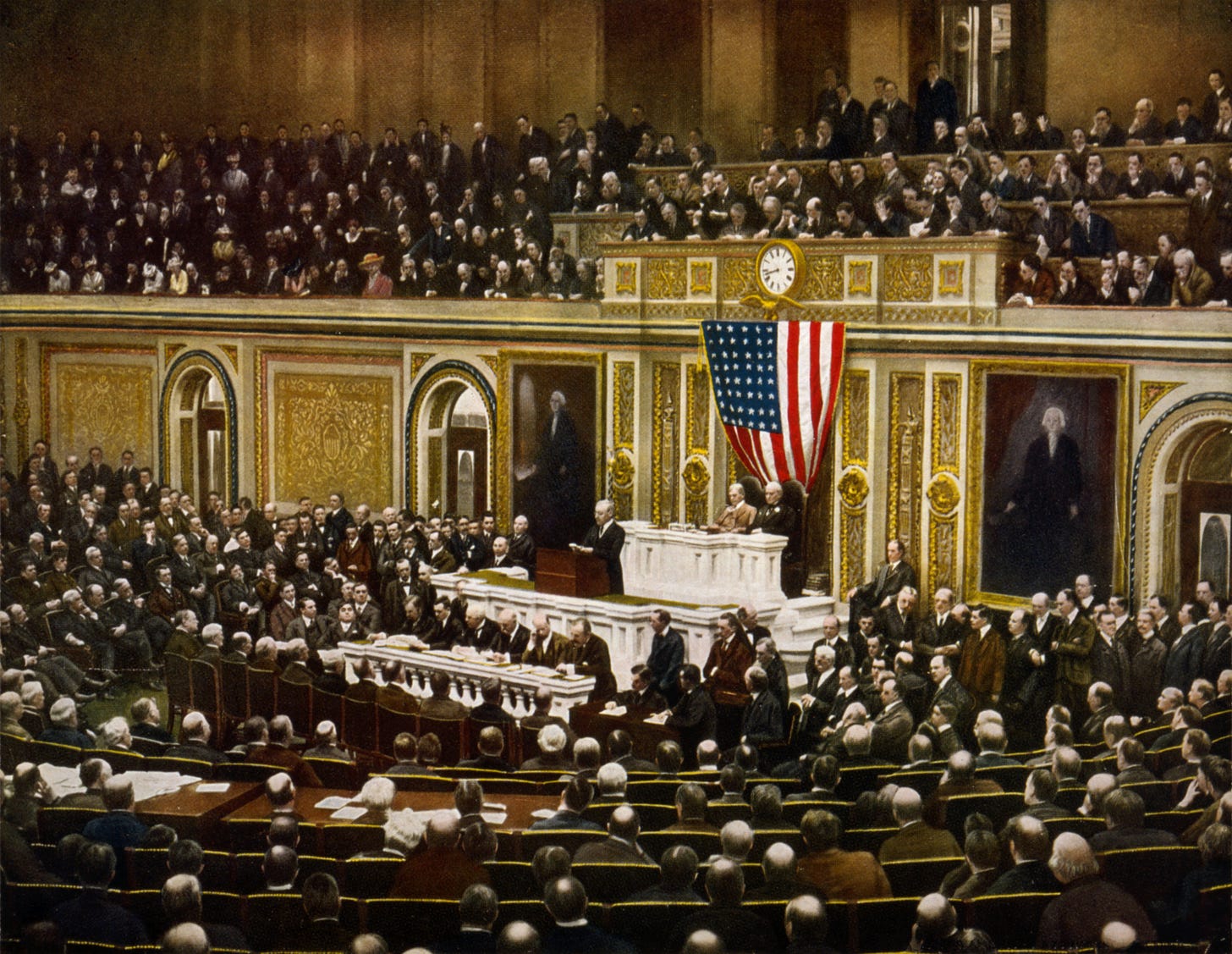

World War I, fought between the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire) and the Allies (Britain, France, and Russia until the revolution of 1917- 1918) began on July 28, 1914. The United States entered the war on April 6, 1917. The war came to an end with the armistice of November 11, 1918. World War I was one of the great catastrophes of human history. Many millions of lives were lost, and untold casualties resulted.

The President of the United States when the United States entered the war was Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924).

Wilson’s speech to Congress asking for a declaration of war was replete with high mindedness and idealism. Here is some of what he said:

We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them. . .

It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance.

But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts - for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own Governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free.13

When the phrase “Wilsonian idealism” is used, passages like this are what is being referred to.

Walter Lippmann was 27 years old when this speech was delivered. He was transfixed by Wilson’s rhetoric. He had glimpsed “a transcendent value in the war which would be redeemed by the better world that would follow.”14 “Our debt and the world’s debt to Woodrow Wilson is immeasurable.”15

Lippmann always found ways to ingratiate himself with the powerful, and 1917 was no exception. He became a trusted member of Wilson’s entourage and was intimately involved in drafting the Fourteen Points, which was Wilson’s peace program.16 He came to believe, in the words of a biographer, “that an imperialist war could be transformed into a democratic crusade.”17 That was the picture in his head – his stereotype of how a just peace making the world safe for democracy could be achieved.

The Treaty of Versailles concluded in 1919 was the reality that exploded Lippmann’s own stereotype of what could be achieved by the war. Public Opinion was written in the shadow of the “ordeal”18 of the negotiation of a peace treaty which thinking people knew very well failed to bring anything approaching a lasting peace. Idealism was crushed by reality. America’s participation in the war and its impotence in crafting a just piece was a great betrayal of the idealism of 1917.

The result was disillusion. The product for Lippmann of that disillusion was the portrait of human affairs distorted by stereotypes which themselves were manipulated by propagandists. “Mr. Wilson’s phrases were understood and endlessly different ways in every corner of the Earth. . . . And so, when the day of settlement came, everybody expected everything.”19 And everybody was disappointed to some degree, some bitterly so.

Where do these observations leave the American citizen in the year of our Lord 2025? Permit me to request that you think for a moment of the phrase “President of the United States.” Can you remember how you felt about this phrase 10 years ago, before Donald Trump burst upon the political scene? What was your stereotype of the American President?

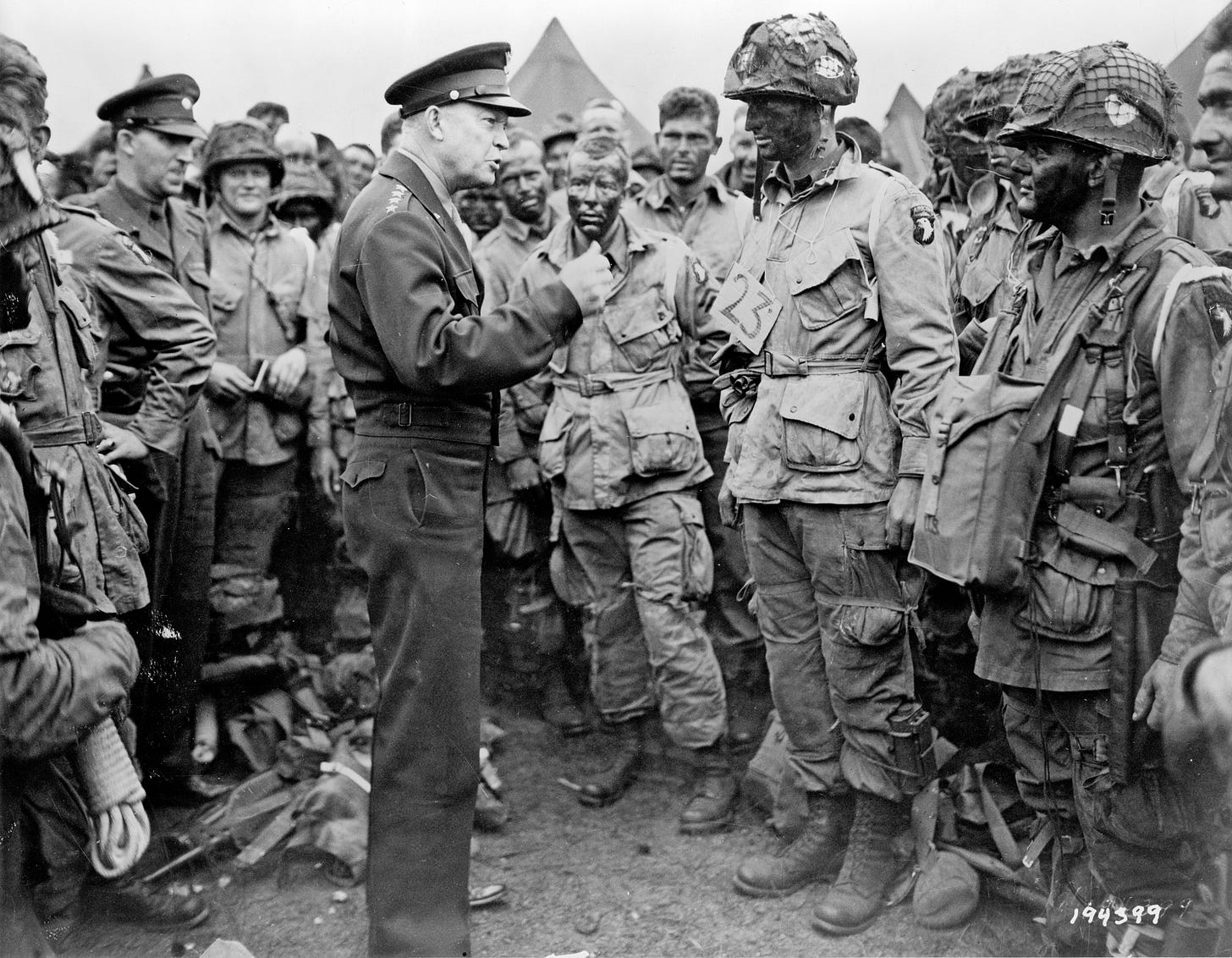

The first President that I can remember seeing on television was Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890 – 1969). My stereotype of the American President begins with him. He was not the perfect person, but he was a dignified man of remarkable accomplishments who put the welfare of the nation ahead of personal considerations. And he took responsibility for what happened on his watch.

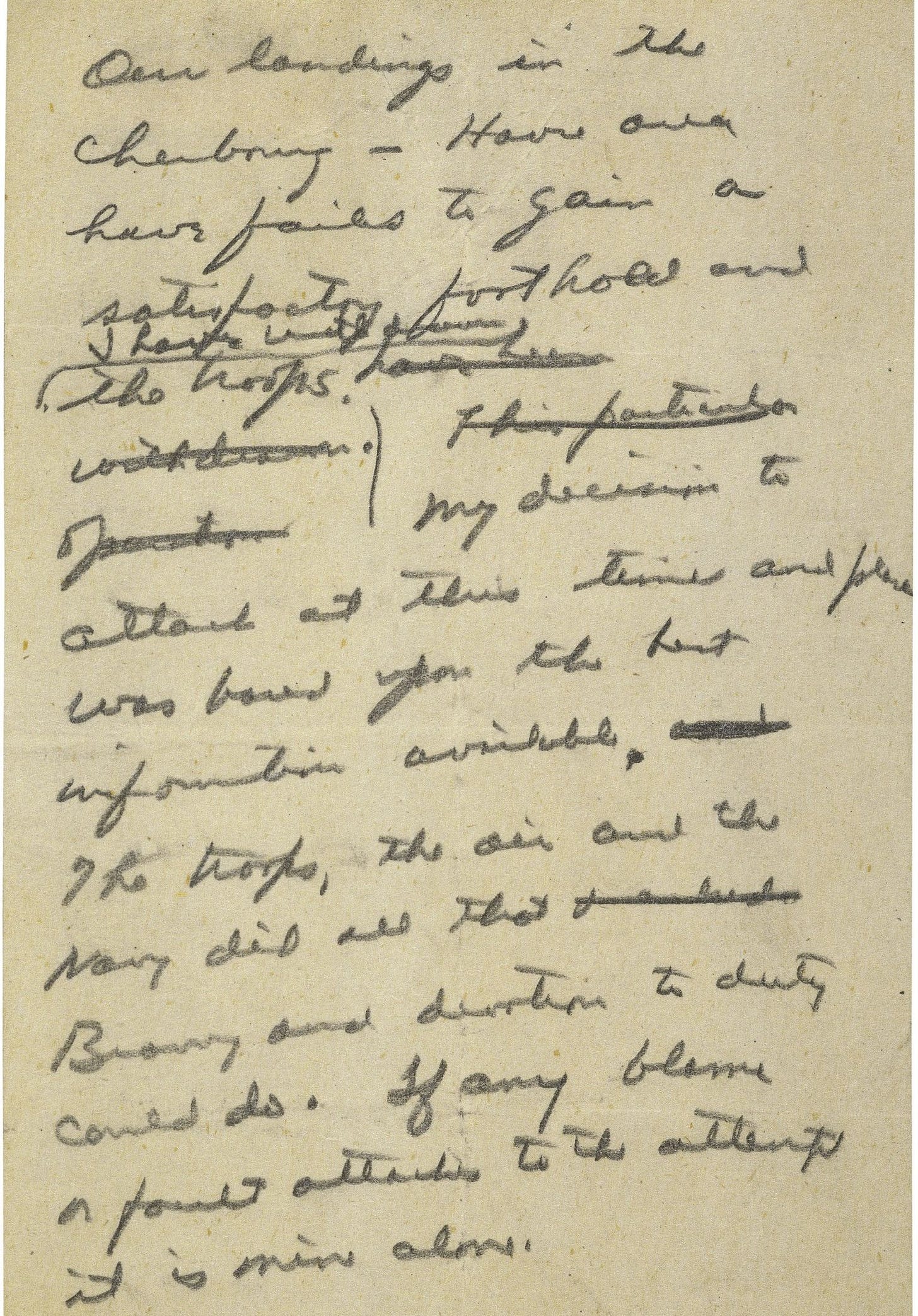

There is no better example of his sense of responsibility than an event which took place before he became President. He was the military commander in overall charge of the greatest amphibious assault in history – the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944. The uncertainties and the tension surrounding this effort were immense. This is the note he wrote and saved the evening before the invasion in case the effort failed:

“Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”20

That was my stereotype of how a leader and especially a President should comport himself. But now we have in Donald Trump a President who, devoid of any real knowledge of a situation, hurries to blame others for anything that goes wrong. His reaction to the tragedy in the air over Washington, DC, on January 29th is the perfect example.21

Please recall now what Walter Lippmann said about the fate of a stereotype challenged by new facts. “[A]ny disturbance of the stereotypes seems like an attack upon the foundations of the universe.”22

That is where I am with regard to the Presidency of the United States. My stereotype of what an American President should be and also of whom Americans would elect to the Presidency has collided with reality. Donald Trump is “an attack on the foundations of the universe.”

In this, I believe I am not alone.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stereotype#:~:text=noun-,ste·%E2%80%8Breo·%E2%80%8Btype%20ˈster%2Dē%2D%C9%99,stereotyped%3B%20stereotyping

Floyd, VA: Wilder Publications, 2014.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 8.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 12.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 13.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 19.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 22.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 42.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 48. Emphasis added.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 55.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 55. Emphasis added.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 57.

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/address-to-congress-declaration-of-war-against-germany

Ronald Steel, Walter Lippmann and the American Century (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2017) Loc. 2523.

Steel, Lippmann, Loc. 2503.

Steel, Lippmann, Loc. 103.

Steel, Lippmann, Loc. 3592.

The word is used by John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1920) p. 253.

Lippmann, Opinion, p. 120.

https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/in-case-of-failure

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/31/us/politics/trump-washington-plane-crash.html

See Footnote 11.

Terrifically insightful and full of home truths. And ultimately, quite sad.