Chapter 34: A Nation in Peril: Lincoln’s Warning

What Lincoln Knew About Lawlessness, Tyranny, and the Fate of Democracy

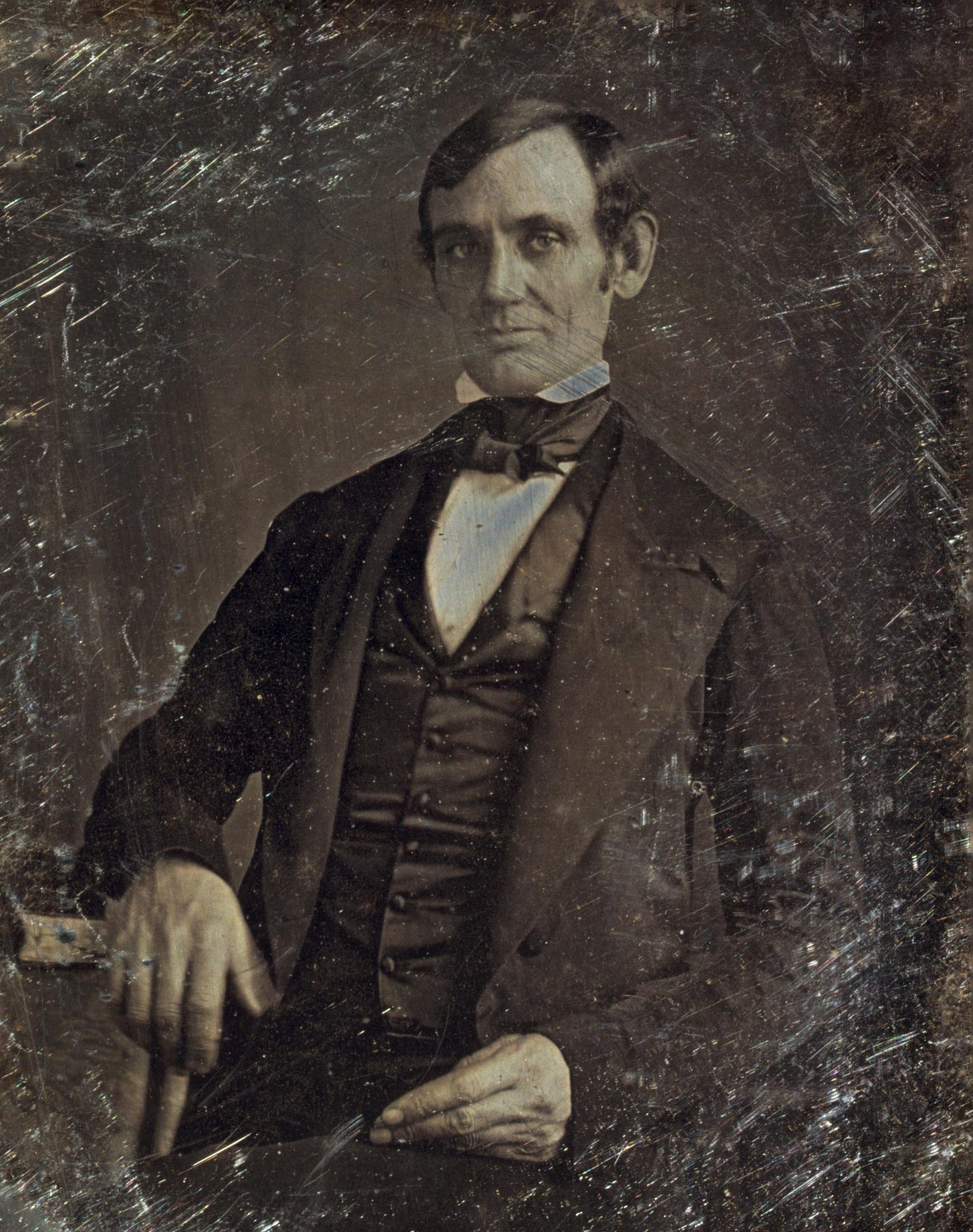

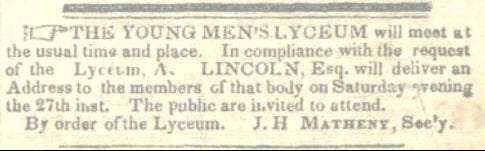

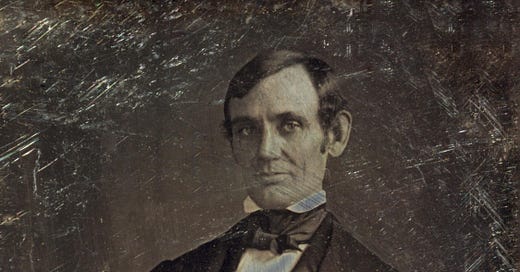

On the evening of Saturday, January 27, 1838, Abraham Lincoln, 28 years of age, walked “through the muddy streets of Springfield [Illinois] to the Baptist Church,”1 the site of a meeting of the Young Men’s Lyceum. His presentation that evening, entitled “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions,”2 resonates with Americans down to the present day. As recently as a week ago, New York Times journalist Thomas L. Friedman concluded a blistering column on the lies and the chaos of Trump’s administration with an important passage from this speech. It “haunts me most,” he wrote.3 The Lyceum has been described as “a good place to deliver a formal speech before Springfield’s professional class, the lawyers and merchants, the doctors and skilled laborers, the up-and-coming young men of ambition constituting the next generation of community leaders, and perhaps even some female spectators.”4 What did Lincoln say on that chilly evening that makes it worth our while to revisit it?

Lincoln begins his presentation by observing that Americans are lucky. “We find ourselves in possession of the fairest portion of the Earth. . . .” The soil, the climate, and the vast expanse of territory are to be cherished. These “fundamental blessings” accrue to us by birthright. “They are a legacy bequeathed us by a once hardy, brave, and patriotic, but now lamented and departed race of ancestors.”5 Perhaps, although he does not mention his name, Lincoln had in mind James Madison (1751 – 1836), often referred to as the “father of the Constitution.” Madison was the last of the founding fathers to pass away. He died on June 28, 1836, at the age of 85.

So Americans have it good. However, Lincoln asks, “At what point shall we expect the approach of danger?” Not from a foreign foe. No enemy army would ever “take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge.” He answers his question by asserting that “if destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author. . . .”6 Thus we must look to ourselves, which was in 1838 and is in 2025 more difficult than looking abroad.

Lincoln professes to find “even now something of ill-omen amongst us.” By that he means “outrages committed by mobs.” The rampages of mobs, he observes, are encountered daily in newspapers. This was true. There were hundreds of riots in the nation during the 1830s.7 They substitute “the wild and furious passions” for “the sober judgement of courts.”8

According to Professor Ellen P. Goodman of the Rutgers University Law School, Lincoln makes three important points about the mob. First, it must be checked. If not, it will grow. Or in Professor Goodman’s typology, “It metastasizes.” Second, “It comes for you.” You may think that the mobs only assail those whom society would be better off without. Don’t kid yourself. Once established, mob rule will encompass the innocent as well as the guilty. Third, the mob “abets tyranny.”9

How does this work? When mobs go unpunished, “The lawless in spirit are encouraged to become lawless in practice; and having been used to no restraint but dread of punishment, they thus become absolutely unrestrained. Having ever regarded government as their deadliest bane, they make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations; and pray for nothing so much as its total annihilation.”10

We are witnessing this phenomenon before our own eyes today. Have we seen a mob go unpunished? Trump issued about 1600 pardons to the mob that traduced the Capitol on January 6. Does anyone think that this mob, having gotten out of jail free, will abide by the laws in the future? And what message do these pardons convey to the Trump-happy mobs of the future?

Consider also the demolition of the government which Trump and Musk are engaged in. Theirs is not an honest effort at reform. Such an effort would take the development of a strategy and care in its implementation, not a chainsaw. Trump and Musk are not about the improvement of government. They are about its elimination.

Professor Goodman’s second point, “It comes for you,” holds that the spirit of the mob “is uncontainable. Once it is loose, arbitrary power reaches for everyone.”11

The Trump administration – the mob incarnate – furnishes an important example of this point. Trump is using antisemitism as a weapon to attack higher education. If he really cared about antisemitism, he would clean it up in his own administration.12

The third point is that the way of the mob leads to tyranny. The way of the mob is the way of chaos. The mob can work to sunder the “strongest bulwark of any government and particularly of those constituted like ours.” That bulwark is “the attachment of the people.”13 Tyrants may arise promising, for example, to make America great again, thus claiming to solve the problem of chaos while actually creating more of it.

In a word, Lincoln asserts that “there is no grievance that is a fit object of redress by mob law.”14

The cases of mobocracy that Lincoln discusses are worth our attention. In Mississippi, the mob’s non-legal process of hanging people ran the gamut “from gamblers [even though gambling was legal] to Negroes, from Negroes to white citizens, and from these to strangers; Till dead men were seen literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every roadside; and in numbers almost sufficient to rival the native Spanish moss of the country. . . .”15 This remarkable turn of phrase anticipates a song written in 1937 about lynching and made famous by Billie Holiday: “Black Bodies swinging in the southern breeze/Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”16

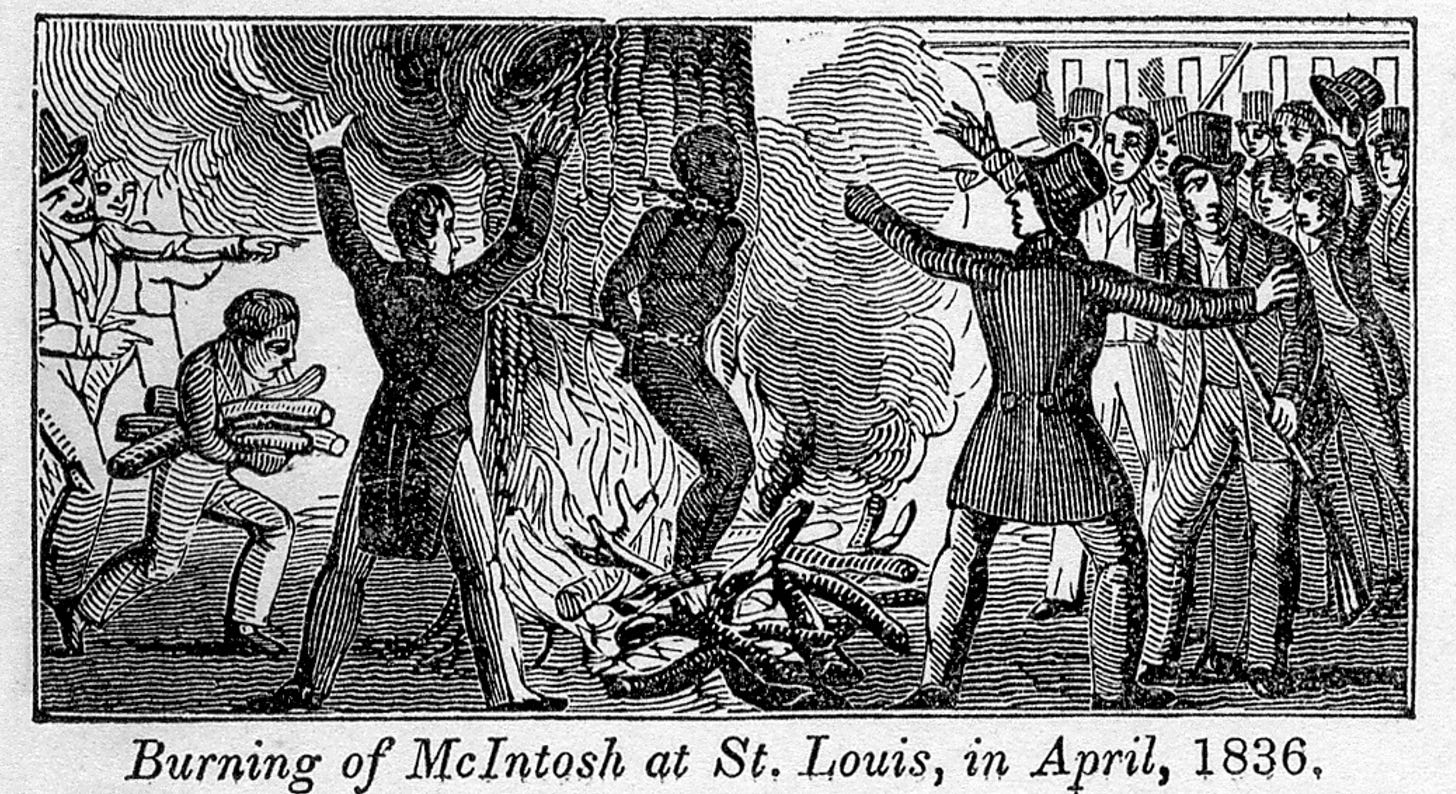

The second case Lincoln describes as "perhaps the most highly tragic . . . that has ever been witnessed in real life. A mulatto man, by the name of McIntosh, was seized in the street, dragged to the suburbs of the city, chained to a tree, and actually burned to death; and all within a single hour from the time he had been a free man, attending to his own business, and at peace with the world.”17

Accounts differ concerning the fate of Francis L. McIntosh (1810-1836). This much appears to be true. He was arrested and jailed in St. Louis on April 28, 1836. A mob broke into the jail, seized him, and tied him to a tree. He was burned to death slowly. According to one narrative, McIntosh begged to be shot and sang hymns while he was dying. A crowd numbering more than two thousand watched him die in agony.18

A grand jury investigated the lynching of McIntosh. Judge Luke E. Lawless informed the grand jurors that if the lynching was the result of the “mysterious, metaphysical, and almost electric phrenzy” of a large number of people rather than the act of “numerable and ascertainable” individuals, then “the safest and wisest course” was not to indict anyone. The grand jury took the Lawless advice – no pun intended.19

Lincoln does not mention the Lawless grand jury instructions. But surely, the “mysterious, metaphysical, and almost electric phrenzy” of the mob was precisely what he was decrying. Indeed, one source asserts that “Delivered in the wake of McIntosh’s lynching, Lincoln’s Lyceum Address was the period’s most influential statement of the dangers that unchecked mob action posed to orderly democratic life.”20 We do not know whether Lincoln’s listeners knew of the fate of McIntosh. It is quite likely that they did. St. Louis is less than 100 miles from Springfield. Moreover, an important incident linked the story of McIntosh to the fate of Elijah P. Lovejoy (1802 – 1837). Without doubt, everyone at the Lyceum knew the story of Lovejoy.

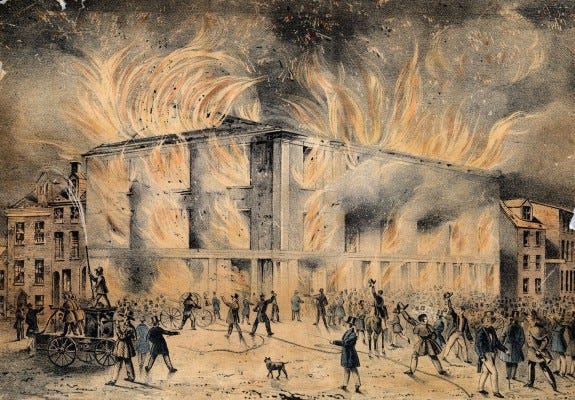

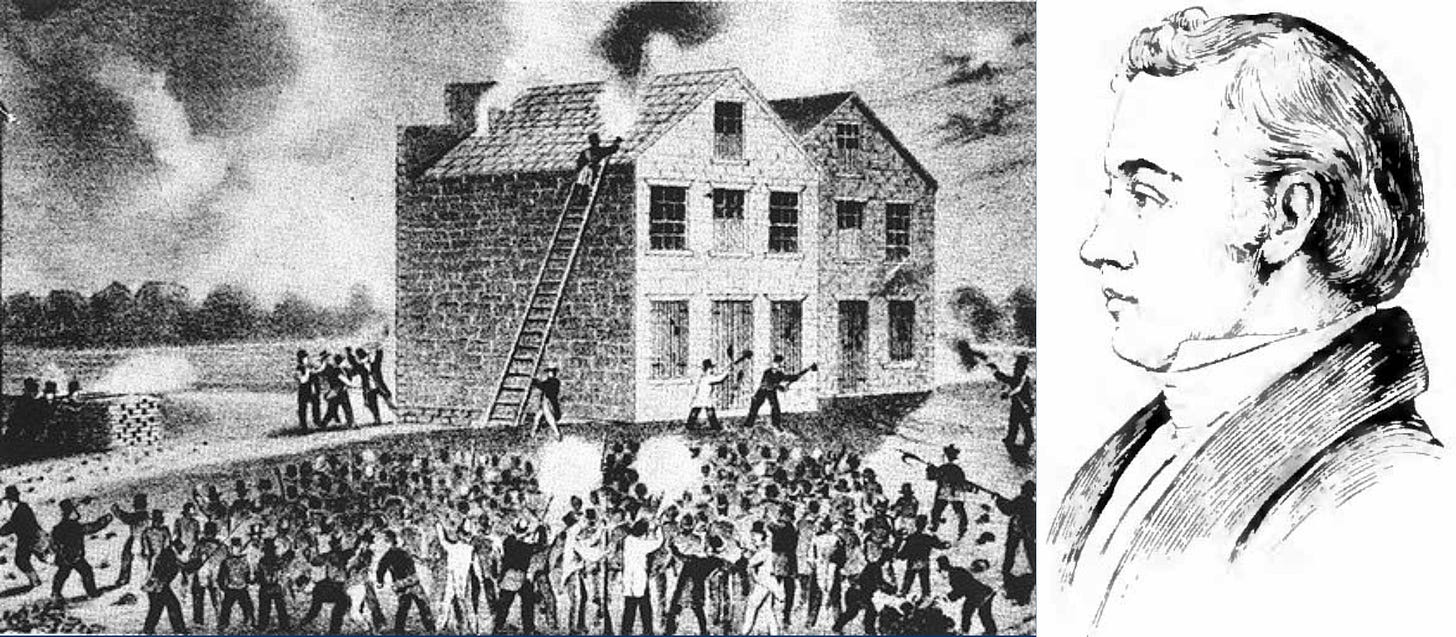

Lincoln does not mention Lovejoy by name. He does not have to. His auditors knew whom and what he was referring to when he observes that that “whenever the vicious portion of population shall be permitted in bands of hundreds and thousands [to] . . . throw printing presses into rivers [and] shoot editors . . .with impunity, depend on it, this government cannot last.”21

Lovejoy was a crusading abolitionist newspaper editor. When Francis McIntosh was murdered, Lovejoy’s newspaper was being published in St. Louis. He asserted on May 5, 1836, that the mob’s action spelled the end of the rule of law and the constitution in the city. His remarks were controversial in St. Louis, to say the least. Facing death threats, he and his family moved across the Mississippi river to Alton, Illinois. On November 7, 1837, a mob attacked his printing press. Seeking to defend it, he was shot five times and killed. He became one of the most important martyrs to the cause of abolition.

What does Lincoln propose to counteract the mobocracy? He called for a comprehensive education campaign the purpose of which was to make clear the vital importance of the rule of law. “Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother to the lisping babe that prattles on her lap-let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in primers, spelling books, and in almanacs; let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay, of all sexes and tongues, and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.”22

As Professor Goodman observes, for Lincoln, “reverence for the law is a demand side proposition. The people have to want it.”23

Do the American people today really want it enough to save it from the machinations of Trump? Lincoln believed that if the people were properly informed of the vital necessity of the rule of law, then they would want it very much indeed. Surely, one reason for the ascendence of Trump has been the failure of America's educators during the past decade.

In advocating the rule of law against the mobocracy, Lincoln sees himself fighting for the victory of reason over passion. Indeed, in the words of one commentator, Lincoln offers a passionate defense of, in his phrase, “cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason.”24

Why is journalist Thomas Friedman haunted by the Lyceum speech? Here is how he ends his remarkable philippic: “’At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected?’ Lincoln asked . ‘I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time or die by suicide.’”25

Friedman concludes that “If those words don’t haunt you too, you’re not paying attention.”

Jason H. Silverman, “The Hedgehog and the Fox: Lincoln’s Lyceum Speech for the Ages,” https://www.friendsofthelincolncollection.org/lincoln-lore/6804/

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

Thomas L. Friedman, “A Great Unravelling Is Underway,” New York Times, March 11, 2025.

Silverman, “Hedgehog.”

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

The quotations in this paragraph are from https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial (New York: Norton, 2010) p. 54.

The quotations in this paragraph are from https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

Ellen P. Goodman, “Tyranny.gov: Technologies of Unreason,” Inaugural Avi Soifer Lecture, University of Hawaii Richardson School of Law, March 7, 2025. Manuscript in author’s possession.

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

Goodman, “Tyranny.”

Jonathan Chait, “Anti-Semitism is Just A Pretext, The Atlantic, March 11, 2025.

Goodman, “Tyranny.”

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

Diana Schaub, His Greatest Speeches (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2021) p. 16.

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynching_of_Francis_McIntosh; See also https://www.jstor.org/stable/45290703; An excellent source concerning the murder of Francis McIntosh is: Paul Simon, Freedom’s Champion (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1994) pp. 47 and 43-60 passim.

Robert M. Pallitto, ed., Torture and State Violence in the United States (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University press, 2011) pp. 62-63.

https://www.umsldigitalhumanities.org/francismcintosh/s/francismcintosh/page/grand-jury

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm

Goodman, “Tyranny.”

Silverman, “Hedgehog.”

Friedman, “Unravelling.

Afraid to read… Looks like a good one though Richard!!!!