Chapter 45: The Stillness Before the Storm

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis and the Fragility of Civilization

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis is a novel published in Italian by Giorgio Bassani in 1962.1 The first English translation was published in 1965. It is one of the greatest Italian novels of the 20th century.

The novel formed the basis of an outstanding motion picture of the same name, released in 1970. Directed by Vittorio De Sica, it won the Academy Award for best foreign language film, among its numerous other accolades.

The novel and the film differ in important respects. Indeed, Bassani and De Sica had a falling out over the adaptation, and Bassani demanded that his name be removed from script-writing credits.2 Both the novel and the film represent the summit of artistic achievement in their respective genres. For the sake of brevity, this chapter will deal only with the film.

The focus of the film is on two Jewish families, and by extension on the Jewish community as a whole, in the Italian city of Ferrara, which is about 70 miles south-southwest of Venice. The years covered are from 1938 to 1943.

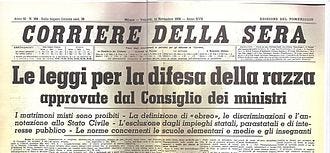

The film begins in an atmosphere of gaiety. A group of young adults are gathering at a tennis court on the grounds of an immense and magnificent estate owned by the wealthy, aristocratic Jewish Finzi-Contini family. The viewer quickly learns that the reason for the gathering at the tennis court on this estate is not a happy one. The fascists have expelled the Jews from the Ferrara Tennis Club. The year is 1938, when “The Laws for the Defence of Race” were promulgated by the fascist government of Italy.3

The response of the Finzi-Continis and some other Jews is to do without such things as the town tennis courts. The Finzi-Continis decide to host a party on the tennis court located on their estate.

The first two players we see on the tennis court are Micòl and Alberto, the daughter and the son of Professor Ermanno Finzi-Contini and his wife Olga. Alberto is handsome and, if not quite frail, not quite rugged either. Shortly before we meet her, Micòl is described as beautiful, tall, and blonde but unpredictable. We see her both drawn to and slightly repelled by one of the guests, a communist and a gentile from Milan.

As the story develops, we encounter various sets of relationships between the characters. We see the world through the eyes of Giorgio who is in his early 20s and completing his university degree in Italian literature. (We are never given his last name, but we will refer to him as Bassani, since he is clearly standing in for the author.) He finds Micòl irresistible and has ever since his youth.

An important moment in the film is a flashback: a service in the synagogue about a decade prior to 1938. The Finzi-Continis and the Bassanis are both members of the congregation. Toward the end of the service, both fathers respectively gather their children by their sides and spread their prayer shawls protectively over them. The scene is brief, but it is the perfect evocation of the world of Ferrara’s Jews at the time.

This is a snapshot of a world which made sense. It was a world of affection and of faith. It was peaceful. Perhaps most of all, it was a world of human dignity. The young Giorgio steals a glance at the young Micòl. He was infatuated with her even then.

Giorgio’s relationship with Micòl shows him as impetuous. She leads him on, only to reject his advances. She is rather cruel to him without appreciating what she is doing.

Eventually, he declares his love for her. She tells him that she could never love him in return. They are too much alike, she feels, two drops of water. She needs to know that Giorgio finds her alluring. With that established, she will go no further. Making love with Giorgio, she observes, would be like making love with her brother Alberto, with whom she has an intensely affectionate relationship.

Believe it or not, there has been a good deal of controversy over Micòl’s character in the novel, the film, and the opera based on this story. One article is entitled “Bashing Micòl.”4 The novel’s author Giorgio Bassani came to her defence. “I am Micòl,” he declared in 1972.5

This is not a particularly long film, just over an hour and a half. But in that brief time, the development of the characters and their relationships is remarkably vivid and cannot be summarized in brief compass.

What can be said is that the interior experiences of the characters and their relationships with one another are played out against real world events which will destroy them and the world that they knew.

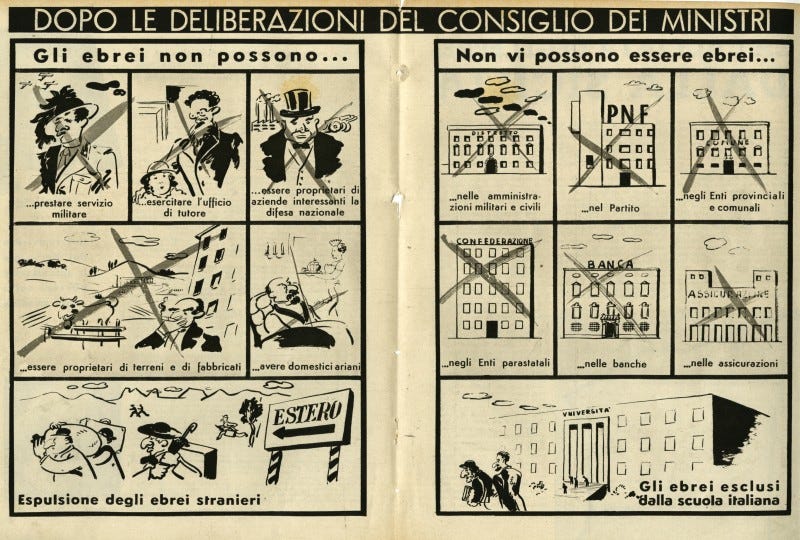

With the Italian Racial Law of 1938, Jews became pariahs. Their oppression in some cases was similar to what the German Jewish diarist Victor Klemperer described as “a thousand mosquito bites.” For example, Jews could no longer be listed in telephone directories. The obituaries of Jews could not be published in the newspapers. As noted, they could not play on public tennis courts. Nor could they employ gentile domestics.

Other provisions of the racial laws were a good deal more distressing. Jews were not permitted to marry gentiles. They could not serve in the armed forces. They were still citizens; but, as Giorgio comments, third class citizens.

Among the most striking of the many remarkable scenes in this film is of Giorgio studying in the library of Ferrara. He is approached by an employee and asked to leave. Does the employee mean that he should move to another table in the reading room? Giorgio asks. No. Leave the library altogether.

Giorgio is angry and demands to see the director of the library. As he raises his voice, others in the library look at him. He goes to the director and confronts him. The director expresses his regret at having to kick Giorgio out but explains that there is nothing he can do. The racial laws and indeed the Holocaust that follows them are portrayed as nobody’s fault.6 But of course, what is nobody's fault is in fact everybody’s fault.

We next see Giorgio with Professor Ermanno Finzi-Contini. The Professor welcomes him into the magnificent library within the Finzi-Contini mansion. There, Giorgio will be able to complete his thesis, with a library better endowed than the one in town.

In this episode, we see the intellectual equivalent of the use of the Finzi-Contini tennis court on the estate. Barred from communal life, the Jews look to use their own resources.

In the words of a reviewer, “Italy in those final post war years is painted by De Sica as a perpetual wait for something no one admitted would come: war and the persecution of the Jews. The walled garden of the Finzy-Continis is his [De Sica’s] symbol for this waiting period. It seems to promise that nothing will change. . . .”7

As one incident leads to another, it becomes clear that everything will change. There is no avoiding the fascist reality. Giorgio and a friend go to a movie. We often go to movies as an escape. Not this time.8 Hitler is shown on the screen as well as scenes of war and goose-stepping soldiers. Giorgio says to his friend that Hitler is scum. The result is a scuffle with the two burly men sitting in the row in front of him, and fortunately Giorgio and his friend leave the theater unharmed.

The most memorable scene in the film is of a Seder at Giorgio’s home. The table is beautiful. The people at the Seder are happy. They are singing together. It is a convivial evening full of warmth.

The telephone rings. Giorgio gets up from the table to answer it. There is silence on the other end. The caller does not hang up but also does not speak. Giorgio hangs up and returns to the Seder.

The phone rings again. Again, Giorgio rises to answer it. More agitated than before, he shouts into the phone. Again no answer. Again Giorgio returns to the Seder table and seats himself. The celebrant next to him says that such phantom phone calls happen to him also. At night.

The phone rings a third time. This time the singing around the table stops. The hosts and the guests are in suspended animation. All watch Giorgio as he gets up, more agitated than before. He angrily answers the phone again.

As all at the Seder table look at him, he says, joyfully, “Alberto.” It is Alberto Finzi-Contini inviting Giorgio to his home. The participants in the Seder breathe a sigh of relief. Things are okay for now.

The reprieve is merely temporary. Soon thereafter, Alberto dies. The Jews of Ferrara are rounded up in 1943 and assembled in rooms in the school Giorgio attended in his youth.

It is in this final scene that De Sica establishes the essential goodness of Micòl. She cares gently for her aged grandmother. She encounters Giorgio’s father and immediately asks after his son. It appears that Giorgio has escaped. She expresses heartfelt, touching relief.

As the film concludes, the El Malei Rachaman, a prayer for the souls of the departed, is heard.9 It is a wrenching ending.

I first saw this film about four decades ago. It was unforgettable. Especially memorable was the scene of the phone calls during the Seder. De Sica is saying that these phone calls are no childish prank. They are designed to terrorize. The far greater terror of the future is left to the imagination. Indeed, that terror is beyond imagining.

What did not cross my mind then but does now is not so much what happened to those fictionalized characters10 then but rather what is happening to us in the United States now. How many people are getting pizzas delivered to their home, communicating the not-so-subtle message that “we know where you live”? How many Americans are being “swatted”? Where is Kilmer Abrego Garcia, and why has he not been returned to the United States as the courts have ordered? How many children – how many thousands of children – abroad have lost their lives because Musk, thanks to Trump, fed USAID “into the wood chipper”?11

The question this outstanding, profoundly troubling, film prompts is: What is next for us? A very difficult question indeed.

A Special Announcement

June 16 marks the 10th anniversary of Trump’s ride down the escalator at his building in New York City to announce his candidacy for the Presidency. In the succeeding decade, he has become the most important American political figure since Franklin D. Roosevelt.

June 16 is an appropriate occasion to take stock of the Trump phenomenon. Two issues strike me as particularly salient.

What accounts for Trump’s rise to power?; and,

What do you think the course of American politics will be in the years to come?

I would like to hear from you on these issues, if you are interested in sharing your views. Please note, there is no need to write anything if you would rather not.

I can be reached at richardtedlow@me.com. Your name will not be mentioned in what I write, but the perspective you communicate will inform the content of the June 16 chapter on the Trump story.

Let me express my gratitude to the readers of Dystopias and Demagogues for your engagement with this project.

My version is: Giorgio Bassani, The Garden of the Finzi- Continis (New York: Harper Collins, 1977).

Norman I. Silber, Outside In: The Oral History of Guido Calabresi (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023) pp. 1388 – 1390; https://blogs.bl.uk/european/2016/09/index.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_racial_laws

https://primolevicenter.org/printed-matter/bashing-micol/

https://primolevicenter.org/printed-matter/bashing-micol/

https://writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/holocaust_new/finzi-contini.php

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-garden-of-the-finzi-continis-1971

https://brightlightsfilm.com/vittorio-de-sicas-garden-finzi-continis-1971/

https://forward.com/culture/438621/50-years-later-the-garden-of-the-finzi-continis-is-a-holocaust-film-like/

See the terrific discussion in Norman I. Silber, Outside In: The Oral History of Guido Calabresi (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023) pp. 1388 – 1390.

https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1886307316804263979?lang=en

Great storytelling and you always tie it with a bow at the end not that it’s a pretty one!!!!