What made Huey Long so dangerous? As noted in the previous post, no less a politician than Franklin D. Roosevelt said that Huey was one of the two most dangerous men in America (the other being Douglas MacArthur). Why?

First, Huey Long had a message: Redistribution of wealth. That is what his Share Our Wealth society advocated. Long launched Share Our Wealth in February, 1934. Within a year, there were 27,000 Share Our Wealth clubs across the country with, 7,682,728 members.1

Second, Huey mastered the media to spread the word. He was a superb speaker on the radio, still a new technology in the 1930s. He was convinced that newspapers were not treating him fairly. Indeed, he labelled them “lying newspapers.” Most offending among these was the New Orleans Times-Picayune, a top executive of which, Alvin Howard, Huey nicknamed “Kinky.” Howard had short curly black hair, and Long’s nickname was meant to suggest that he was part African-American. As Huey said when he was a Senator, The Times-Picayune “claims to be a paper for white supremacy, but one of the leading executives . . . is part [N]egro.” So he founded his own newspaper, the Louisiana Progress in 1930. This was renamed the American Progress in 1935 and achieved a circulation as high as 1.5 million. He also made extensive use of circulars and of sound trucks when campaigning.2

Third, by 1935 Huey Long had a cadre of supporters personally loyal to him throughout the nation.

Let’s compare these assets to the strengths of Donald Trump as the 2016 election approached, through his term in office, and down to the present day.

First, message. Trump has one. It is MAGA, Make America Great Again. Trump said that he came up with the phrase himself. In fact it was used in Ronald Reagan’s Presidential campaign in 1980 and also by Bill Clinton in 1991, when he announced his campaign for the Presidency the following year. Though not original, Trump has made his own.

Second, media. Trump is a superb communicator. For over a decade beginning in 2004, he was the host and star of “The Apprentice,” a reality television program that attracted high ratings. Trump’s use of Twitter from May 4, 2009, to January 7, 2021 (when he was kicked off the platform), was unexcelled. He tweeted about 57,000 times. His handle, @real Donald Trump, boasted 88.7 million followers at the time of his suspension. Between Twitter (now X, on which he has been reinstated) and Fox News, which has been a veritable house organ for him, Trump has remade the map of political communication in the United States. And, of course, as did Long, Trump has relentlessly attacked what he has called the “fake news” media.

Third, the individual. “Jesus is my savior . . . Trump is my President.” The attachment of devoutly religious people to Trump is intense. It is hard for those outside the cult, and probably for Trump himself, to understand it.

The importance of this personal allegiance in politics cannot be overstated. A vivid illustration is the fate of Joe Biden. He was the Democratic nominee for the Presidency until his catastrophic debate performance on June 27 created a rebellion in the party. He desperately clung to his nomination until July 21, when he was booted off the ticket. No one complained. No one agitated to “bring Biden back.”

Imagine if the Republican party attempted to rid itself of Trump in the same way. There would be an uproar. The Republicans know it. That is why they do not try.

Huey Long knew how to keep his name before the public during the 1920s. On the Public Service Commission of Louisiana, he launched a battle against Standard Oil and its founder John D. Rockefeller that he lived off politically for his whole life.

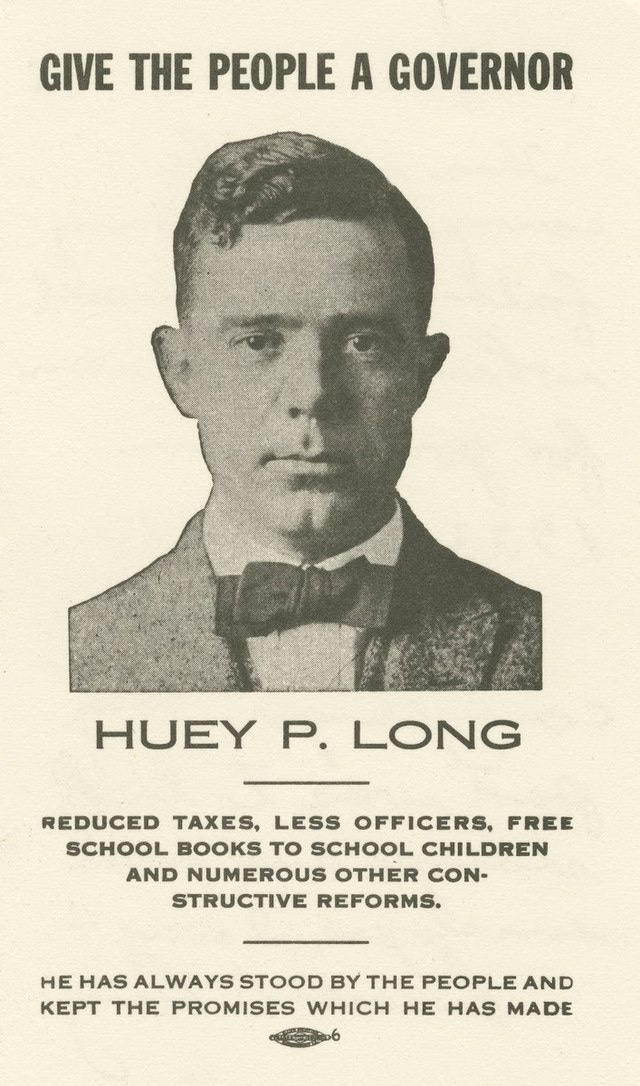

In 1924, Long ran for governor. In a close contest, he lost. This was the only election he ever lost.

In 1927, Long launched his second campaign for the governorship. “Every man a king,” he declared, borrowing a phrase from the populist politician William Jennings Bryan, “but no one wears a crown.” Whatever that might mean, the slogan worked. When it was combined with Long’s unquestioned charisma as a campaigner, he won the election.

In 1928, Huey Long became the 40th governor of Louisiana. He was 35 years old, the youngest governor in the history of the state. In the seven years that followed (Long was governor from May 21, 1928 to January 25, 1932 and U.S. Senator from January 25, 1932 to September 10, 1935), Long ran Louisiana like no one had ever run a state previously or has since.

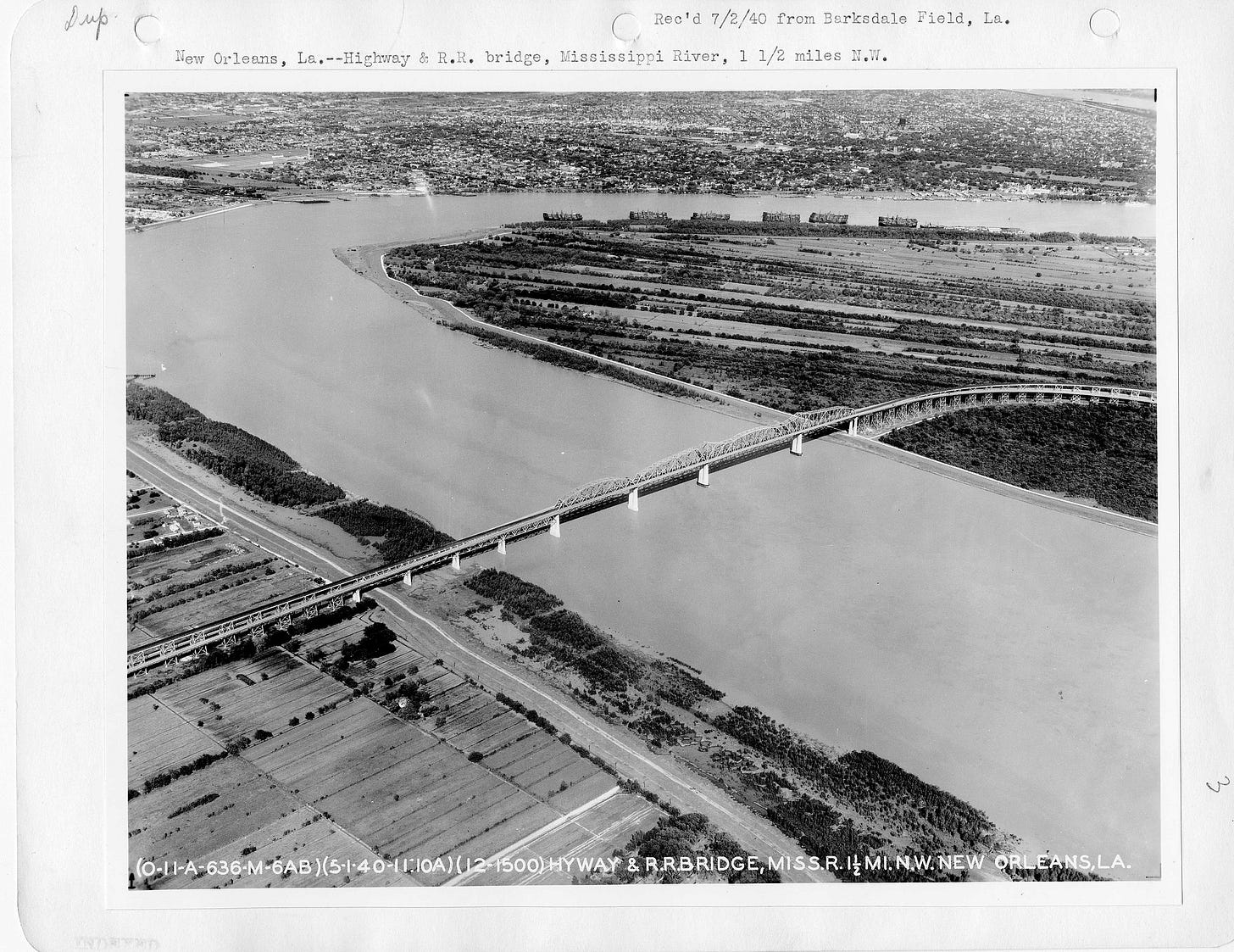

Unlike most of the other demagogues with whom American history is so richly endowed, Long delivered on many campaign promises. These included, according to a biographer: “[T]he construction of roads and bridges, an increase in the facilities of the charity hospitals in New Orleans and Shreveport, the improvement and humanizing of services in state hospitals for victims of metal disorders and epilepsy, the expansion of Louisiana State University and the creation of its medical school, the founding of night schools for Illiterates, the furnishing of free books to school children, the enlargement of the port of New Orleans, the bringing of natural gas to New Orleans, the construction of one of the largest airports in the country at New Orleans, and the erection of a new capitol [building in Baton Rouge].”3

Let’s look at roads and bridges specifically. When Long became governor, there were 331 miles of paved highway in Louisiana. During his administration, the state built 1,583 miles of concrete roads, 718 miles of asphalt roads, and 2,816 miles of gravel roads. All this plus 111 bridges. In 1931, Louisiana employed more men building roads than any other state in the nation – 22,200 compared to 20,597 in New York.4 According to the census of 1930, the population of Louisiana was 2,101,593 and of New York 12,588,066.

Louisiana State University held a special place in Huey’s heart. He was much taken with the model of Frederick the Great -- as he explained in 1935, “the greatest sonofabitch who ever lived.” “’You can’t take Vienna, Your Majesty. The world won’t stand for it,’ his nitwit ambassadors said. ‘The hell I can’t,’ said old Fred. ‘My soldiers will take Vienna and my professors at Heidelberg will explain the reasons why.’”5 “Hell, I’ve got a university down in Louisiana that cost me $15,000,000 that can tell you why I do like I do.”6 (For the record, Frederick the Great never did take Vienna.)

All this looks pretty good, especially in the context of the somnolent, self-interested government that preceded Long in Louisiana. When you look under the hood, however, the story is not quite as rosy. Take the roads, for example. They were of poor quality. And the corruption involved in their building was little short of melodramatic. Roads that came in at $45,000 to $50,000 per mile should have cost about a sixth that much.7

It is true that the public works were real, tangible accomplishments. And government jobs during the Great Depression were a precious commodity. But did the roads and the other accomplishments have to be achieved at the price of decency in government? “How was it,” as one journalist wrote not long ago, that other states were “able to provide free textbooks and build roads and bridges without routinely declaring martial law, putting machine gun implacements in government offices, and eliminating local government?”8

From the beginning, Huey had his eye on national power. He intended to be President, and he intended to treat Washington politicians the same way he treated those in his home state. Soon after becoming governor, he built a new executive mansion in Baton Rouge modeled on the White House so that he could “be used to it when he got there.”9 He said “We’ll use Louisiana as a pattern” after becoming President.10 As far as any opposition he might encounter, every man, he believed, had something to hide. “I can frighten or buy ninety-nine out of every hundred men,” he believed. Said a Louisiana politician, “He liked to break people. . . .”11

Long was elected to the United States Senate on September 7, 1930. His term was to begin on March 4, 1931. However, he was still the governor of the state; and the lieutenant governor was one of his enemies. So Huey remained governor and did not take his seat in the Senate until January 25, 1932.

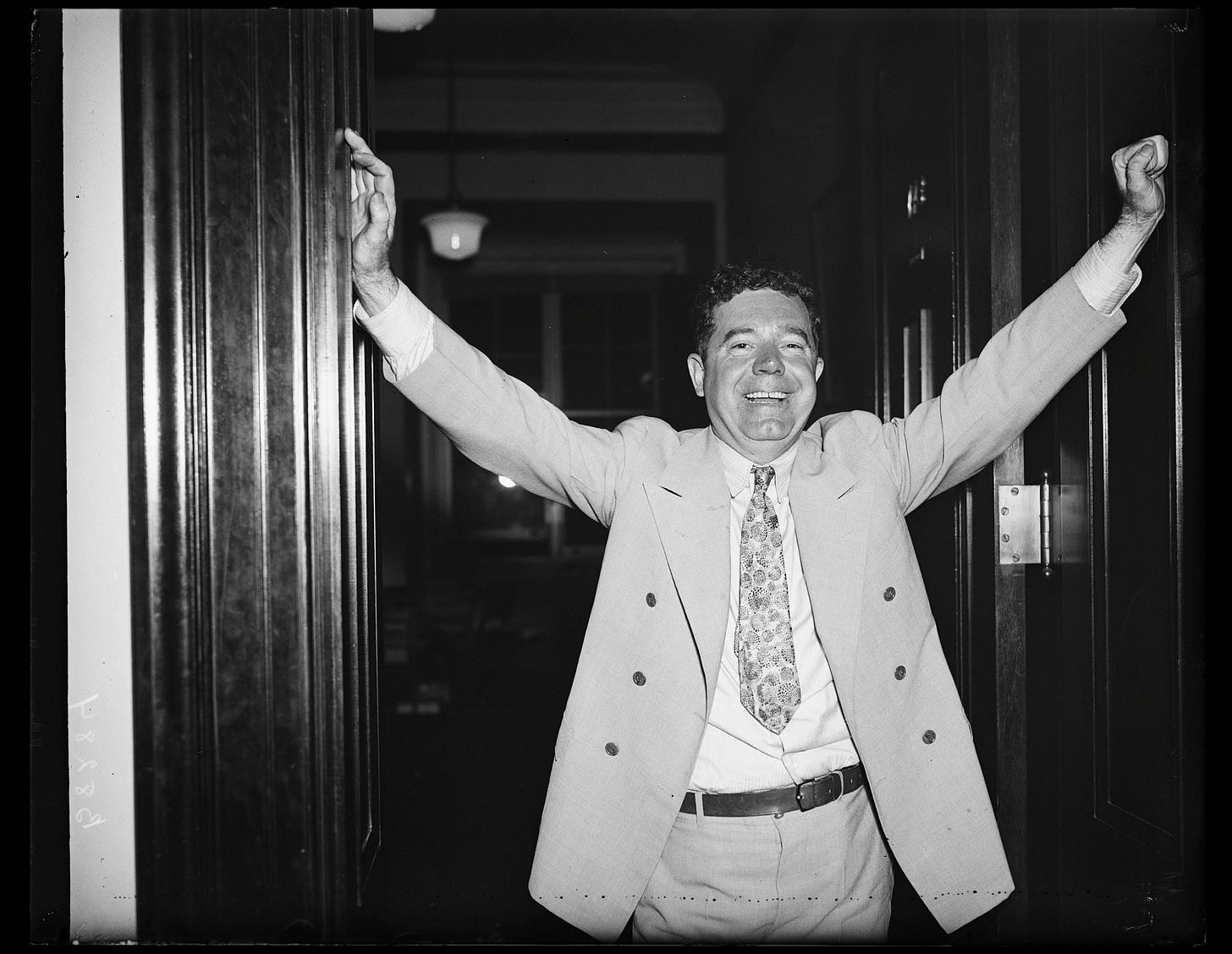

Huey broke every norm of Senate behavior. He was brash. He filibustered. He delighted in being the center of attention. He played a noteworthy role in securing the Democratic nomination for the Presidency for FDR at the Democratic National Convention in 1932. It soon became clear, though, that Long had no intention of playing second fiddle to anybody.

Roosevelt invited Long to the White House in June of 1933. Dressed in a brilliant white suit and wearing a straw hat, Huey glided into the President’s office. In what has been called “a studied gesture of brazen disrespect,” he did not take off his straw hat except to tap the President’s knee when making a point. Apparently he addressed Roosevelt as “Frank,” rather than as “Mr. President.”12

In the face of such provocation, “Roosevelt remained calm and superficially amicable.”13 But he knew he had to cast Long adrift.

That would not be easy. Long had a self-financing political machine back home. And although almost all his fellow senators could not stand him, he was developing a national and even a trans-Atlantic reputation.

Long was aiming for the White House and not just to visit. He began mocking Roosevelt. He had his own devoted following, to which he distributed his autobiography, Every Man A King, in 1933. The following year he organized the Share Our Wealth movement, which had the potential to be the core of a political organization to rival the two major parties. By the middle of 1934, he was receiving more mail than all the other 95 senators (there were 48 states until Alaska and Hawaii were admitted to the union in 1959) combined. Senate mail was delivered in two trucks, one for Huey and one for everybody else. He was receiving more mail than the President.14

Some observers believed that a Long candidacy in 1936 might siphon off enough votes from FDR to cost him the election. By 1940, Huey figured that the nation would be desperate; and then it would be his turn. He would be only 46 years old.15

How much of this speculation was real? How much fantasy? Roosevelt’s political advisors thought it was very real indeed. A man named W. E. Warren, the president of a struggling Montana bank, wrote Roosevelt in 1935 that “Huey Long is the man we thought you were when we voted for you.”16

Of course, we will never know how things might have turned out. Huey Long did not live to be 46. He did not live to be 43.

With the perspective of almost 100 years and with the lens of the unexpected political career of Donald Trump, how are we to evaluate Huey? What should we think about him? What does his career teach us about us?

It is generally recognized that Long transformed Louisiana into “the closest thing to a dictatorship that America has ever seen.”17 While serving in the Senate, he continued to run the state through a sycophantic successor governor and a supine state legislature. At one point, the state House passed 44 bills in 22 minutes.18 The state Senate clocked in at in an average of under three minutes per bill.19 Long’s legislation eviscerated local government in the state. A member of the opposition who changed sides to back him observed, “Others had power in their organization, but he had power in himself. And he brought them all to their knees.”20 “I used to try to get things done by saying ‘please,’” Huey said. “That didn’t work and now I’m a dynamiter. I dynamite ‘em out of my path.”21

“They say they don’t like my methods,” he said. “Well, I don’t like them either. I really don’t like to do things the way I do. I’d much rather get up before the legislature and say, ‘Now this is a good law; it’s for the benefit of the people and I’d like for you to vote for it in the interest of the public welfare.’ Only I know that laws ain’t made that way. You’ve got to fight fire with fire.”22

And in a phrase that ought to be engraved on his tombstone, Huey said that “The end justifies the means.”23

Of course that is not the issue. The question is: What ends justify what means? One sympathetic biographer wrote: “He wanted to do good, but to accomplish that he had to have power. So he took power and then to do more good seized still more power, and finally the means and the end became so entwined in his mind that he could not distinguish between them, could not tell whether he wanted power as a method or for its own sake. He gave increasing attention to building his power structure, and as he built it, he did strange, ruthless, and cynical things.”24

A southern demagogue well-known in the 1960s was the Governor of Alabama, George C. Wallace, Jr. (1919 – 1998). He won 46 electoral votes in his Presidential bid in 1968, which was powered by his declaration that: "There's not a dime's worth of difference between the Democrat and Republican parties." This was his version of Huey’s “High Popalorum and Low Popahirum.” (See the video above.)

Stephen Hess, “The Long, Long Trail,” American Heritage, Volume 17, Issue 5 (August, 1966)

The sources for this and the preceding paragraph are: T. Harry Williams, Huey Long (New York: Knopf, 1969) pp. 660-661; William Ivy Hair, The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long (Louisiana State University Press, 1991) Online edition, Locations 3341 and 5159; Glen Jeansonne, Messiah of the Masses: Huey P. Long and the Great Depression (New York: Longman, 1993) p. 127

Willliams, Long, p. 546

Williams, Long, p. 546

William E. Leuchtenburg, “FDR and The Kingfish,” American Heritage, Volume 36, Issue 6 (October/November, 1985)

Williams, Long, p. 492

Jeansonne, Messiah, pp. 68-69

Nicholas Lehmann, “The Not So Great Dictator,” The New York Review, May 28, 1992

Leuchtenburg, “FDR.”

Williams, Long, p. 741.

Williams, Long, p. 751

David M. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999) p. 236

Alan Brinkley, Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression, (New York: Vintage, 1983) p. 75

Jeansonne, Messiah, p. 115

Brinkley, Voices, p. 210

Brinkley, Voices, p. 234

Kennedy, Freedom, p. 236

Jeansonne, Messiah, p. 142

Brinkley, Voices, p. 39

Williams, Long, p. 737

Jeansonne, Messiah, p. 82

Williams, Long, p. 748

Williams, Long, p. 749

Williams, Long, p. 751