The Vietnam War ended on April 30, 1975; so this year is the 50th anniversary of its conclusion. A company called Vermont Bicycle Tours runs tours in Vietnam. “Quiet villages set among rice paddies, pagodas, and sugarcane fields contrast starkly with bustling cities that move at lightning speed.”1 Reading this description will cause cognitive dissonance for anyone old enough to remember America’s war in Vietnam.

This is a war that a lot of people would like to forget. If you want proof of this assertion, consider the inimitable Trump administration. The administration instructed its top diplomats in Vietnam to avoid events that were held in Vietnam marking the half century since the war’s conclusion. John Terzano, a veteran of the Vietnam War, said "I really don’t understand it. As a person who has dedicated his life to reconciliation and marveled how it’s grown. . . , this is really a missed opportunity.”2

Try though Trump and others might to cast a spell of forgetfulness over the war, that cannot be done. If you speak to American men in their 70s and 80s, you will find, perhaps to your surprise, that they are reevaluating how they handled themselves during the tumultuous, passionate, years from 1961 to 1973.

Dating the onset of the Vietnam War is not easy. The year 1955 is a good choice, meaning that the war lasted for two decades. The active involvement of the United States did not begin until the Kennedy administration succeeded the Eisenhower administration on January 20, 1961. There was already “active guerilla warfare” in South Vietnam at that time.3 Neither North Vietnam nor the United States wanted this warfare to escalate, but escalate it did.

“Step-by-step, both sides expanded their commitments to South Vietnam between 1961 and 1965, the critical years of decision-making that culminated in the dispatch of American combat forces” in large numbers.4 On May 20, 1961, President John F. Kennedy (1917 – 1963) sent 400 United States Army Special Forces to South Vietnam to train South Vietnamese soldiers. On November 22, 1963, Kennedy was assassinated; and his Vice President, Lyndon B. Johnson (1908 – 1973) became President.

Johnson was the Democratic Party nominee for President in 1964. Johnson and the Democrats won an overwhelming victory, in part because they portrayed Barry Goldwater, his Republican opponent, as a dangerous war monger. But with the election over, Johnson himself greatly increased American commitment to the war in Vietnam.

On March 2, 1965, Operation Rolling Thunder began. This was the name given to the bombing of North Vietnam by the U.S. Air Force. Eventually, a staggering 7.5 million tons of bombs were dropped on areas of South Vietnam controlled by the Viet Cong, on North Vietnam, and on neighboring Laos and Cambodia. This is more than the total tonnage of bombs dropped during all of World War II.5 The United States also dropped millions of gallons of herbicides on Vietnam in an effort to defoliate the jungle.6

Johnson sent about 185,000 troops to Vietnam in 1965. 1969 saw the peak number of Americans there, 549,500.

Why? What made such a gigantic commitment to this little sliver of land which was poor in natural resources and no threat to American security worth making? This question is especially urgent given that, as one historian observed, Kennedy and Johnson escalated “not because they were confident of victory but because they feared the consequences of defeat.”7 They were not playing to win. They were playing not to lose. Neither man lived to see the final American defeat.

Why did Kennedy and Johnson fight this war, and why did Richard Nixon (1913 – 1994), who became President on January 20, 1969, continue it? The causes and the duration of America’s war in Vietnam are complicated, but three key issues can be isolated:

The Cold War, the domino theory, and the long shadow of 1938;

The arrogance of power; and,

The perceived domestic cost of not fighting the war.

The Cold War, the domino theory, and the shadow of 1938. The Cold War commenced following World War II. The term “Cold War” refers to the conflict for global dominance between the United States and the Soviet Union joined later by China. The term is contrasted with “hot war,” which is a war in which both sides are shooting at each other. The Cold War was often referred to as a battle for hearts and minds.

The domino theory is the idea that if the free world (the United States and its allies – this was never referred to as the capitalist world) lost one country to the communists, then the next country would be lost, then the next, and the next, and so on like a row of falling dominoes.

This theory had the effect of making every country on Earth, no matter how irrelevant to America’s national security, seem vitally important. Neither North nor South Vietnam mattered to American security.

However, if you believe in the domino theory, if South Vietnam fell to the communists, the rest of what was once French Indo-China (Cambodia and Laos) would fall too, then Thailand, then Malaysia, then Singapore, then Indonesia, and so on. And before you knew it, the ‘commies’ would be in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California.

The shadow of 1938 refers to the Munich agreement of that year. By the terms of this agreement, the British and French tried to appease Adolf Hitler by permitting him to annex the Sudetenland, the German-speaking enclave in Czechoslovakia. The agreement was reached on September 30, 1938. Hitler promised that the Sudetenland would be his last territorial demand in Europe. Hitler lied. German troops occupied Prague in March of 1939.

You could look at Hitler’s actions from the occupation of the Rhineland in 1936, to the annexation of Austria in 1938, to the Sudetenland, and to Czechoslovakia, and behold all the dominoes falling.

The lesson: Concession leads to world war. Or as Pete Clemenza explains to Michael Corleone in The Godfather, “You gotta stop them at the beginning. Like they shoulda stopped Hitler at Munich, they should never let him get away with that, they were just asking for big trouble. . . .”8

The arrogance of power. The United States had a staggering array of weapons and a huge military establishment. Vietnam had next to nothing. It was hard to imagine that what Lyndon Johnson referred to as a “damn little pissant country”9 could hold out against the United States. Henry Kissinger (1923 – 2023), Nixon’s national security advisor, agreed with this assessment, commenting that “I can’t believe that a fourth-rate power like North Vietnam doesn’t have a breaking point.”10 It was a case of David and Goliath. But people didn't pause to remember that David won.

The domestic political situation. An American President, especially if he were a member of the Democratic Party, ran a grave political risk if he “lost” Vietnam to the communists. President Harry S Truman (1884-1972) was mercilessly attacked by the Republicans for “losing” China.

President Richard Nixon did succeed in extricating the United States from Vietnam, but only after a heavy cost in lives for a war which could be endured but could not be won. Nixon’s campaign is alleged to have scuttled a peace deal that Johnson worked on toward the end of 196811 because he did not want the Democrats to get the credit for ending the quagmire prior to the election that year.

Nixon was overwhelmingly reelected in November of 1972. Seven days after his second inauguration, on January 27, 1973, America’s involvement in the Vietnam War finally ended. And what so many people had feared about losing the war turned out to be untrue. The United States lost the Vietnam War, and yet won the Cold War. Suppositions to the contrary were proven incorrect. In his famous, some would say infamous, book about the war, Secretary of Defense from 1961 to 1968 Robert S. McNamara (1916 – 2009) said, “[W]e were wrong, terribly wrong,”12 about the war. True.

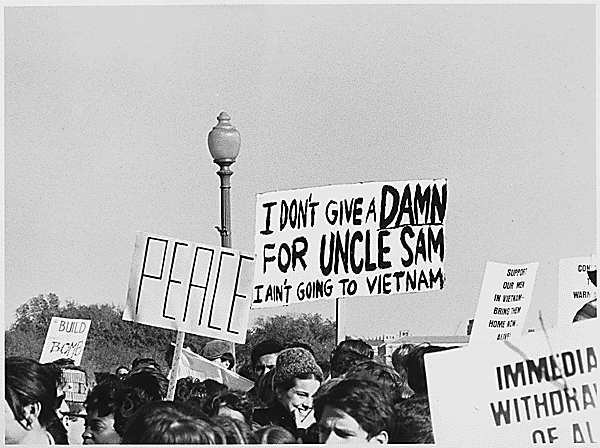

The Vietnam War was the cause of an enormous amount of pain to the millions of people involved. And it generated a great deal of moral confusion. What role should a conscientious American play? Should he go to war? Should he burn his draft card? Should he go to war and then agitate against it once he returns to the United States, as the Vietnam Veterans Against the War did?

Here is one story about the moral confusion generated by the Vietnam War. A well-known historian named Joseph J. Ellis is a specialist in the history of the early American republic. In 2001, he won the Pulitzer Prize. In addition to his specialty, he taught a course both at Mount Holyoke College and at Amherst College on the Vietnam War. The course was high impact.

Here are some student comments about Ellis’s Vietnam War course.

"He was the veteran who came back and participated in the antiwar movement. . . .” "The course was something so central to him because he did serve there, while his experience with Jefferson and Adams is otherworldly, so distant in comparison.” “When he is teaching, he uses different anecdotes from his own personal experience in Vietnam . . . to help us understand it better. But he doesn't want to force feed the class his personal views. He does have a very objective view of the war. He is able to step back from his own war experience in Vietnam.”

Ellis’s service in Vietnam, according to a student, "changed the dimension of the course. His having that personal experience gave the course more gravity. He was honest about his experience in the war and its effect on him as a person. The course allowed me to imagine myself in the circumstances he faced. Having the course taught by someone who was there helped. The course was very meaningful for me. I'm staring down the barrel of graduation, and I think back to that course and how the war was a test of his manhood . . . It almost made me a tad jealous of people who had that choice to make - whether to go or not. He had gone, taken the test of manhood, and passed it."13

Professor Ellis never served in Vietnam.

When confronted by a reporter by this fact, uncovered because of the publicity for his Pulitzer Prize, Professor Ellis said, “I'll have to suffer the consequences of this." And "I believe I am an honorable man."14

Making choices and coming to terms with oneself in the face of the staggering violence of the Vietnam War was not, and is not, easy.

It is a shame that Trump told our ambassador and other top officials in Vietnam not to participate in the commemoration of its 50th anniversary. People may want to forget the Vietnam War. But they cannot. And they should not.

https://www.vbt.com/destinations/asia-and-oceania/vietnam/

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/22/world/asia/us-diplomats-vietnam-war-anniversary-trump.html

Mark Atwood Lawrence, The Vietnam War(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008) p. 67.

Lawrence, Vietnam, p. 67

https://www.thetimes.com/world/asia/article/the-vietnam-war-ended-50-years-ago-but-it-is-still-killing-people-f9kfpv26z?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK236347/

Lawrence, Vietnam, p. 68.

Mario Puzo, The Godfather, (New York: Penguin, 2019) p. 129.

Lawrence, Vietnam, p. 99.

Lawrence, Vietnam, p. 145.

Lawrence, Vietnam, p. 136.

Robert S. Mcnamara, In Retrospect (New York: Random House, 1996) p. xx.

Walter V. Robinson, “Professor’s Past In Doubt Discrepancies Surface In Claim Of Vietnam Duty,” Boston Globe, June 18, 2001.

Robinson, “Past.”