“The central idea pervading this struggle is the necessity that is upon us of proof that popular government is not an absurdity.” Abraham Lincoln, May, 18611

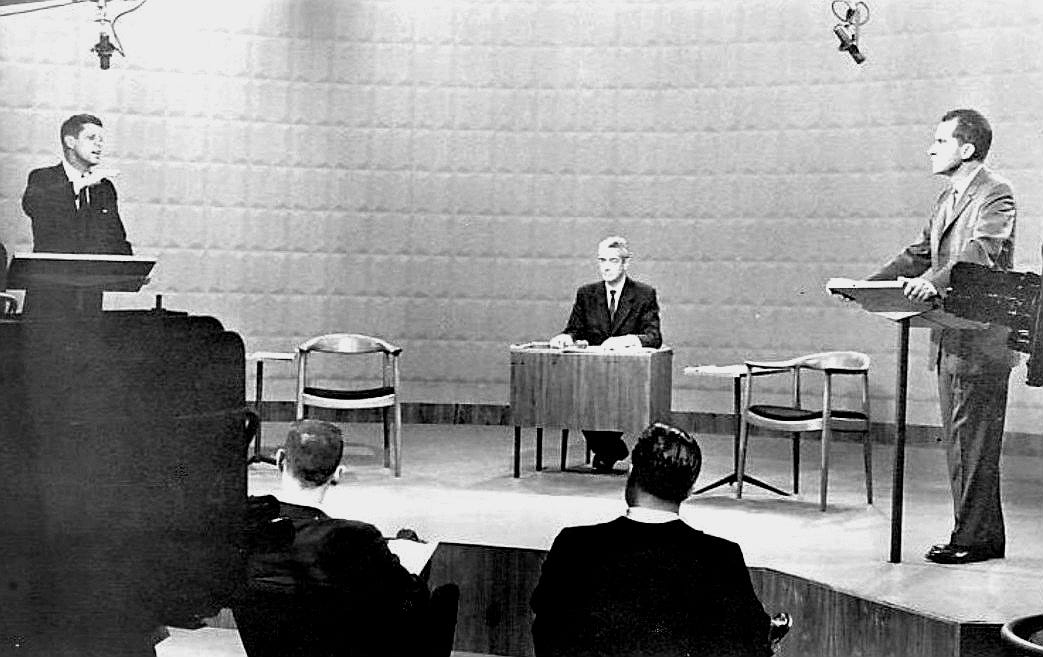

The first Presidential debates took place in 1960. Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice President Richard Nixon faced off in four hour-long encounters. Of these, the most important was the first one which took place on September 26 in Chicago. An estimated 70 million Americans saw this debate on television. Perhaps a sixth of that number listened to it on radio. (The nation’s population that year was just under 180 million.)

If you would rather not watch the entire hour, I suggest you take a look at the question Sander Vanocur asked Richard Nixon at 25:54.

Nixon was confident prior to the debate. He had used television successfully as long ago as his immortal “Checkers” speech in 1952.2 He felt his command of the facts was masterful and that he would prevail.

This was the first encounter of its kind. Television had swept the nation following World War II. Almost everyone who could afford one owned a set. These were not the televisions we are used to seeing now. The screens were small, and televisions were usually kept in the living room in those days. Viewers often gathered around the set with their families and watched together. Many people came to believe that this debate placed Kennedy on a par with Nixon merely because the two appeared on the same stage at the same time.

“We just elected a President. It all happened on television.” That is what Don Hewitt, who produced this debate and went on to an exceptionally successful career producing 60 Minutes, said following the broadcast.3 Among the most enduring conclusions to emerge from the first debate is that more people who saw it on television thought that Kennedy had won, but more who listened to it on the radio thought that Nixon had won.4 This conclusion is being advanced currently in discussions of Biden, Harris, and Trump. Is it true? Probably not in the way people believe.5 Was this first debate as important as contemporaries and later commentators believed? Yes.

The consensus was that Kennedy looked appealing while Nixon’s self-presentation was off-putting. Hewitt observed that Kennedy had been “campaigning in an open convertible in southern California looking tan and fit like a young Lochinvar. This guy was a matinee idol.” Nixon, on the other hand, “looked green, sallow, [and] needed a shave.” He “looked like death warmed over.”6 Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley said, “My God, they’ve embalmed him before he even died.” The following day, the Chicago Daily News ran the headline “Was Nixon Sabotaged by TV Makeup Artists?”7

Nixon himself recounted that Rosemary Woods, his personal secretary who would later become famous during the Watergate scandal8, told him that her parents phoned to ask “if I were feeling up to par.” They said that “I looked pale and tired.” Nixon’s mother called Woods to ask “if I were feeling all right.”9

What are we to make of the oft-repeated television/radio breakdown of the reactions to the two candidates? To state the obvious, when you are going to be seen through an appliance in the living room of millions of people, you better be extraordinarily careful about what you look like. Are your clothes the right color (even in the world of black and white television, this was important)? Are you clean-shaven? Do you perspire under the hot lights illuminating a television studio? If so, what is the best makeup for you prior to the event? Doubtless, more such questions could be asked.

It was pointed out at the time and has been since that issues like those just mentioned don’t have anything to do with the qualities the nation needs in its President. But that was the reality of the television age. As Nixon wrote two years after his defeat in the 1960 election, “the basic mistake I had made [is that] I had concentrated too much on substance and not enough on appearance.”10 Critics not only of Nixon but of the whole debate enterprise focused on this very issue.

The idea for the debates arose because the television networks were petrified that they would be subject to greater federal regulation in the wake of the quiz show scandals of the late 1950s. They endeavored to buy off politicians by offering free time for the debates.11

The four “great debates” of 1960 showed the influence of the supposedly discredited quiz shows. As in the Twenty One program, whose most famous contestant was Charles Van Doren, two adversaries faced each other and endeavored to deliver point-scoring answers. One commentator believed the debates succeeded “in reducing great national issues to trivial dimensions. With appropriate vulgarity, they might have been called the $400,000 question (Prize: a $100,000-a-year job for four years).”12 The $64,000 Question and Twenty One were the two most widely watched quiz shows.

The Canadian scholar and public intellectual Marshall McLuhan used the debates to illustrate an idea much discussed, especially in the advertising industry, during the 1960s. He believed that “the medium is the message.” In the debates, “those who heard them on radio received an overwhelming idea of Nixon’s superiority. It was Nixon’s fate to provide a sharp, high definition image . . . for the cool TV medium that translated that sharp image into the impression of a phony.”13

Journalist Theodore H. White established his career with the publication of The Making of the President 196014 McLuhan took White to task because the student of television would be dismayed by White’s treatment of the debates. White offered “statistics on the number of sets in American homes and the number of hours of daily use of these sets, but not one clue as to the nature of the TV image or its effects on candidates or viewers. White considers the ‘content’ of the debates and the deportment of the debaters, but it never occurs to him to ask why TV would inevitably be a disaster for a sharp, intense image like Nixon’s and a boon for the blurry, shaggy texture of Kennedy.”15

Let us consider politics today in light of these observations.

First, appearance matters a great deal. In his June 27 encounter with Trump, Biden was not only unable to complete a thought, he was stiff, pale as a ghost, and looked lost. Trump looked like he had just stepped off the golf course.

Second let us take another look at the phrase “the medium is the message” and use it as a lens through which to apprehend Trump.

Here is an example of Trump at a rally:

This is as completely bizarre a statement as anyone seeking to be President of the United States has ever made. Not incidentally, it illustrates the degradation of political discourse since 1960. It is inconceivable that either Kennedy or Nixon would ever have wandered around crazy town like this.

What are we to conclude? The message is not the words Trump speaks. The words themselves have no meaning. McLuhan said of Hitler that “His thoughts were of very little consequence.”16 That has to be true of Trump. To understand the phenomenon of Trump, we must understand that what he says (sharks, boats, electrocution) is not as important as the way he says it. What maters is the man himself. Or, more accurately, the Trump persona – the supposedly fabulously successful business tycoon who has deigned to depart his gilded surroundings to MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!!! The Cincinnatus of Mar-a-Lago.

Trump cuts through the overgrown vines of modern communication from social media platforms all the way to traditional methods of communication and simplifies the landscape. “Look at me! Listen to me!! I am the answer!!!” The medium by which the words are transmitted – Donald J. Trump – is the message, all rolled up into one.

This reality encapsulates the threat Trump and his demagogy pose to democracy in America. Think of what Abraham Lincoln said as the Civil War was getting underway. His goal was to demonstrate that popular government is not an absurdity. For popular government to function, an educated electorate is required. But Trump says: Follow me. If one choses that path, education is unnecessary. Thinking stops. When Taylor Swift endorsed Kamala Harris, she wrote, “I’ve done my research, and I’ve made my choice. Your research is all yours to do, and the choice is yours to make.” That is an invitation to education.17 Trump, in sharp contrast, offers us “alternative facts.”18

“As our case is new, we must think anew and act anew,” Lincoln wrote in December of 1862.19 What I am hoping for is a new way to think about Trump. We have to translate what he says into what he actually means. We need to decode him. The place to begin is by never ceasing to insist that “alternative facts” are falsehoods. The truth will set us free.

James M. McPherson, “Out of War, a New Nation, Prologue Magazine, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Spring, 2010)

For Nixon’s comments on the “Checkers” speech, see Richard Nixon, Six Crises (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010) pp. 73-130. Exceptionally incisive is Garry Wills, Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man (New York: Open Road Integrated Media Online) pp. 29 – 45

“Don Hewitt discusses the Kennedy-Nixon Debates,” emmytvlegends.org, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bmw7hH0kawA

This questionable observation is widely disseminated. For example: History.com editors, “The Kennedy-Nixon Debates,” April 25, 2023, https://www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/kennedy-nixon-debates. Or see, James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945 – 1971 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996) p. 1571 online.

Essential is Jon Bruschke and Laura Divine, “Debunking Nixon’s radio victory in the 1960 election: Re-analyzing the historical record and considering currently unexamined polling data,” The Social Science Journal, Vol. 54, Issue 1 (March, 2017), pp. 67-75. Scholars believe that in general political debates are not as consequential as is commonly thought. See Rachel Nuwer, “Presidential Debates Have Shockingly Little Effect on Election Outcomes,” Scientific American, October 20, 2020 and especially Caroline Le Pennec and Vincent Pons, “How Do Campaigns Shape Vote Choice? Multi-Country Evidence from 62 Elections and 56 TV Debates,” National Bureau of Economics Working Paper No. 26572. Of course, as the hapless Biden proved on June 27 of this year, debates can matter a great deal.

Hewitt, “Kennedy-Nixon.”

“Kennedy-Nixon,” History.com. Editors Updated: April 25, 2023 | Original: September 21, 2010

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, The Final Days (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975) pp. 90 – 100.

Nixon, Crises, pp. 336 – 342.

Nixon, Crises, pp. 336-342

Richard S. Tedlow, “Intellect on Television, The Quiz Show Scandals of the 1950s,” American Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Fall, 1976) pp. 483 -495.

Daniel J. Boorstin quoted in Tedlow, “Intellect,” p. 494.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: Gingko Press, 2013) p. 326.

New York: HarperCollins e-book.

McLuhan, Media, p. 360.

McLuhan, Media, p. 327. Italics added.

Swift, Taylor [@taylorswift]. Kamala Harris Endorsement. Instagram, 11 Sept. 2024, https://www.instagram.com/taylorswift/p/C_wtAOKOW1z/

Rebecca Sinderbrand, “How Kellyanne Conway ushered in the era of ‘alternative facts,’” Washinton Post, January 22, 2027.

“Annual Message to Congress – Concluding Remarks,” December 1, 1862, Abraham Lincoln Online.