Chapter Six: Can It Happen Here?

Fascism, Fear, and Freedom: How Close Is the Threat to American Democracy?

According to Euripides, “A slave is he who cannot speak his thought.”1

“Can it happen here?” is a question that was asked with urgency in the United States during the 1930s.

Journalist Dorothy Thompson (1893–1961) interviewed Adolf Hitler in December of 1931 and published I saw Hitler! the following year. She was unimpressed: “He is the very prototype of the Little Man.”2 She believed he would never be the dictator of Germany. Fourteen months after her interview, Hitler proved her wrong; and in 1934 the Gestapo paid her a visit and gave her 24 hours to leave Germany.

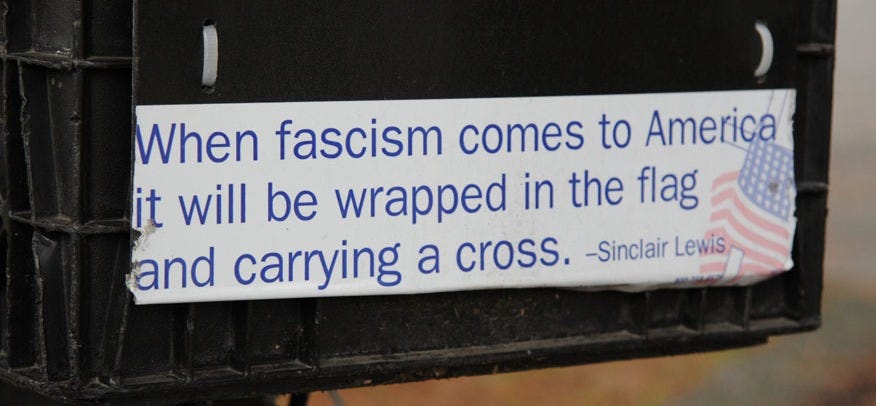

Thompson was married to novelist Sinclair Lewis during this time (the marriage lasted from 1928 to 1942); and influenced by her, Lewis dashed off during six weeks in the summer of 1935 his novel entitled It Can’t Happen Here.3 The novel was inspired not only by Thompson’s views about Hitler but probably more immediately by her views about Huey Long (see Chapters Four and Five of this Substack). It has been said that one reason Lewis wrote the novel was to make it more difficult for Huey, referred to by some as “Der Kingfish,” to prevail in the 1936 election.4

Lewis’s novel was published on October 21, 1935. No one was worried about Huey Long by then. An assassin shot him on September 8, and he died two days later. Nevertheless, the novel sold very well.

During the 1930s, many Americans were concerned about the possibility that the United States might provide a breeding ground for fascism. The reason for this concern was the rise of fascist dictatorships in Spain, Italy, and preeminently Germany. The vision dancing before American eyes is captured by the following photograph:

In the age of Trump, Lewis’s novel has been reborn. In November, 2016, it soared to the number one slot on Amazon’s Classic American Literature list. Penguin Modern Classics came out with a new edition on January 20, 2017, the day of Trump’s inauguration.

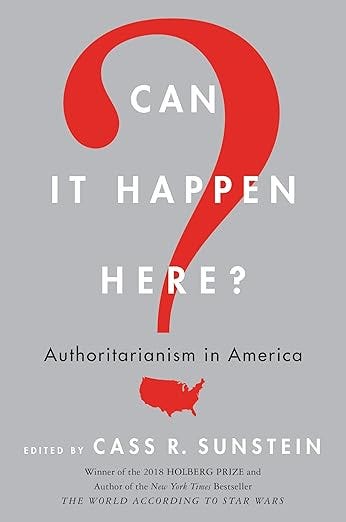

Here is one example of the current interest, which I chose because of the prestige of its contributors. It is a collection of essays published in 2018 edited and introduced by Cass R. Sunstein entitled Can It Happen Here?: Authoritarianism in America.5

In his Introduction, Sunstein imagines a situation in which a successful terrorist attack prompts President Trump to declare martial law. Things deteriorate from there. “Since the 1930s,” he writes, “the question of whether it can happen here typically asks about the rise of fascism. But that’s a failure of imagination. Things can go wrong in a thousand different ways . . . .”6 He further observes that things actually have gone wrong for segments of the population over the course of American history. Enslavement of African-Americans. . . . Decades of Jim Crow following slavery. . . . . Internment of Americans of Japanese background during World War II . . . . And other examples “less bad, but not good” such as the demagogy of Senator Joe McCarthy In the 1950s.7

Confusion about this topic is inadvertently captured by a comparison of Sunstein’s “Introduction” and the chapter which he contributed to this collection. He concludes his “Introduction” with: “So, can it happen here? . . . . Absolutely.”8 However, in Sunstein’s chapter entitled “Lessons from the American Founding,” he writes, “In my view, it really can’t.”9 What is one to make of these two statements?

In another essay in the same volume, Noah Feldman comes to grips with what the words “it can’t happen here” actually may mean. Most interesting is his treatment of the pronoun. “[W]hat is the ‘It’ that cannot happen? Authoritarianism? Extra – constitutional government? Rights suppression? Some combination?”10 His answer is that if “It” refers to fascism, it probably won’t happen. But if the “It” “is the gradual and not-so-gradual transformation of political institutions and practices, not only can ‘it’ happen - ‘it’ has happened, repeatedly.”11

We will return to the issue of what the “It” is that either can or can’t happen here. Before doing so, a couple of comments about this book are in order.

Some contributors to this collection believe that the web of institutions that make up our complicated government can prevent the rise of authoritarianism. If Donald Trump is re-elected, that proposition will be put to the test.

Trump in the White House a second time will be an angry, vengeful man. He has promised to use the tools of government to attack those who have opposed him. This is one promise that there is reason to believe he will keep. There is no need for some terrorist attack to provide cover. Trump says he wants to be a dictator on day one. Judging from Project 2025, his dictatorship will probably not be gradual. The contributors to this book (and remember it was published in 2018) underestimated the menace Trump represents.

Another problem with the book is that it leaves the reader unclear about the role of the Constitution in Trump’s political ascendancy. Some believe the Constitution will protect us. Others are not so sure.

“The United States has the world’s oldest democratic constitution still in force,” write Tom Ginsburg and Aziz Huq.12 Is that good or bad? “Because of its age,” they observe, “the Constitution doesn’t reflect the learning from recent generations of constitutional designers.”13

Jack M. Balkin asserts that “Trump is merely a symptom. He is a symptom of a serious problem with our political and constitutional system . . . . [W]e are in a period of constitutional rot.”14 The Constitution has not dealt successfully either with the rise of an oligarchy or with the advent of globalization.

Ask yourself this question: If you could solve one problem with our Constitution what would it be? My answer is the electoral college. Strangely, this unique structure is barely mentioned in this lengthy book. Sunstein writes, “The electoral college, puzzling to many modern observers, is another important example of the general effort to promote deliberation among those with different perspectives, (see [The Federalist] No. 68).”15 What does that mean?

Trump poses two distinct problems. First, how did this shameless demagogue get elected in 2016. Second, how is it possible that he may very well be elected again in 2024 after all that has happened? Balkin asserts that “Trump represents the end of a cycle of politics rather than the future of politics.”16 Remember, once again, that this book was published in 2018. Even with that caveat, it appears that Balkin did not appreciate Trump’s magnetism.

There are differences between Trump I (2016) and Trump II (2024). But there is one very important thing in common. If it were not for the electoral college – if the Presidency were decided by popular vote – Trump would not have been elected in 2016 nor will he be elected in 2024.

What can be done about the electoral college? To eliminate it would require a Constitutional amendment. Our Constitution has become effectively impossible to amend.

There is another approach which, while it would not eliminate the electoral college, would reduce its disastrous consequences. The House of Representatives was frozen in size at 435 in 1929. In 1930, the census showed that the population of the United States was 123,202,624. Thus in 1930, the average member of the House of Representatives had 283,224 constituents.

According to the 2020 census, the population of the United States was 331,449,281. So the average representative was responsible for 761,952 people. The nation’s population at the first census in 1790 was 3,919,023. There were 105 members of the House that year, so each member represented 37,324 people. Thus, the number of people per representative has increased by a factor of about 20. Would anyone concerned about the original interpretation of the Constitution think this is what the framers wanted?

There are 650 members of the House of Commons, and the population of the United Kingdom is about 67 million. That is one member for about 103,100. Can anyone assert that our present ratio is acceptable?

What would happen if the membership in the House of Representatives were greatly increased?17 The answer is that the number of electors would also be greatly increased. This would not solve all the problems of the electoral college, but it might mitigate them. It would certainly make the electoral college more reflective of the nation’s population as a whole, and that’s a good thing.

Let us return to the question of the antecedent of “It” in the assertion that “It can’t happen here.” Please look at the quotation from Euripides at the beginning of this post. If it did happen here, we would not be able to speak our thought.

And please look again at two of the previous posts. Here is how Chapter Two begins:

Andy Grove, CEO of Intel during its glory days from 1987 to 1998, recounted the following story from his youth in Soviet-controlled communist Hungary. It was dangerous, he writes, to tell a joke to the wrong person.

“Two men are ogling a spanking new western car. One of them says, ‘Isn’t this car a wonderful testimony to the technological capabilities of our friendly Soviet Union?’ The other man looks at him scornfully. ‘Don’t you know anything about cars?’ he asks. The first man replies, “I know about cars. I don’t know about you.”

And this is from Chapter One:

For the bulk of Northeim’s inhabitants [Northeim is a small German town that aligned itself with the Nazis], the price was what Allen [the author of the Northeim story] in his most effective chapter labels “the atomization of society.” There arose “the breakdown of interhuman trust under the impact of terror and rumor.” The Nazi Party was everything. “[I]ndependent social entities” of which there had been a thick network in Northeim died out or were terminated. Some of these just withered on the vine. What was the point of a social gathering if you had to be careful what you said? In these years, the “German glance “arose. This “consisted of looking over one’s shoulder before saying anything that might mean trouble if overheard.”

What is at stake? What is the “It” in the assertion that “It can’t happen here? “It” is freedom of thought. Freedom of expression. Freedom to congregate with people we trust.

Can it happen here? Yes. Why? For two principal reasons. First, the electoral college, even if expanded, makes it possible for a fervent minority to seize control of the Presidency. Second, the Supreme Court has established Presidential immunity.

Quoted in Edith Hamilton, The Greek Way (New York: Norton, 1983) p. 31. Hamilton did not provide a footnote for this quotation. I assume it is from “The Phoenician Women.”

Quoted in Peter Kurth, American Cassandra: The Life of Dorothy Thompson (Lexington, MA: Plunkett Lake Press, 2012) p. 241.

New York: Doubleday, 1935.

William Ivy Hair, The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long (Louisiana State University Press, 1991) online edition, Location 5142.

New York: HarperCollins 2018.

Sunstein, “Introduction,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen, p. ix.

Sunstein, “Introduction,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen, pp. ix – x.

Sunstein, “Introduction,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen, p. ix.

Sunstein, “Lessons from the American Founding,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen, p. 54.

Noah Feldman, “On ‘It Can’t Happen Here,’” in Sunstein, ed., Happen, p. 157.

Feldman, “Here,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen p. 161.

Tom Ginsburg and Aziz Huq, “How We Lost Constitutional Democracy,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen p. 127.

Ginsburg and Huq, “Constitutional Democracy,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen p. 155.

Jack M. Balkin, “Constitutional Rot,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen p. 19.

Sunstein, “Lessons,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen, p. 71.

Balkin, “Constitutional,” in Sunstein, ed., Happen p. 32.

See the following sources: https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/publication/downloads/2021_Enlarging-the-House.pdf

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/02/28/danielle-allen-democracy-reform-congress-house-expansion/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/07/20/gerrymandering-electoral-college-solution-democracy/

Wow, this knocked me out. I felt a tightness in my throat as I finished it. A great deal of the present confusion in this country as well as the recent past here and in Europe is explained in a clear, if frightening, way. The looming problem is clearly the electoral college. Bu what to do about it? I think I feel an urge to start praying....