Chapter Two: Darkness at Noon

The Logic of Absurdity: What Happens When Dystopian Regimes Take Us Through the Looking Glass

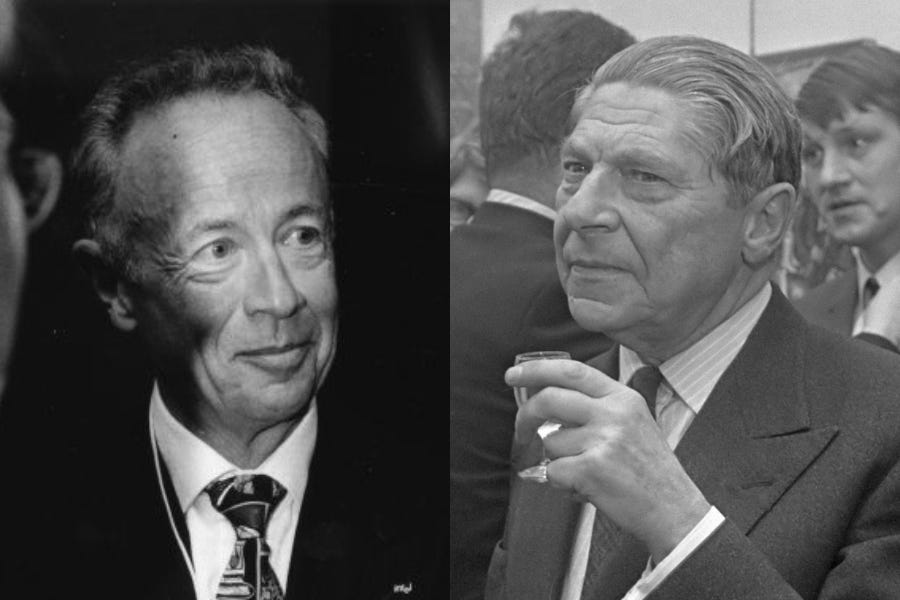

Andy Grove, CEO of Intel during its glory days from 1987 to 1998, recounted the following story from his youth in Soviet-controlled communist Hungary. It was dangerous, he writes, to tell a joke to the wrong person.

“Two men are ogling a spanking new western car. One of them says, ‘Isn’t this car a wonderful testimony to the technological capabilities of our friendly Soviet Union?’ The other man looks at him scornfully. ‘Don’t you know anything about cars?’ he asks. The first man replies, “I know about cars. I don’t know about you.”1

It is a revealing anecdote. The totalitarian world is a world without law. A world without law is a world without trust. The question facing the United States today is whether or not we, during this strange summer of 2024, might be hurtling in this very direction.

In 2005, when I was working on Andy Grove’s biography, he told me that in order to understand his father I should read a book written by a Jew born in Budapest (as Andy was) named Arthur Koestler. The book is Darkness at Noon.2 I read it in 2005, and I have just re-read it.

Darkness at Noon is a novel which makes understandable the otherwise incomprehensible show trials in Moscow which took place from 1936 to 1938.3 These trials featured old Bolsheviks confessing to crimes they had not committed before being murdered by Stalin’s henchmen. What was the purpose of this bizarre theatre? What did Stalin’s dystopia create?

In Darkness at Noon, Koestler takes us through the looking glass. He shows us the “mixture of logic and absurdity” which characterized this grotesque charade.4 The absurdity has always been evident to outsiders. But it is the logic of the world inside that generates the absurd outcome which Koestler makes understandable.

And it is the logic that is terrifying. If one accepts the axioms of the oppressors, the show trials – the confessions of men who were innocent of the charges brought against them – begin to make sense. When you accept certain axioms, insanity becomes normalized.

One axiom is the necessity of putting yourself on the side of the inexorable march of history. You must facilitate the historically-determined future. And you must understand that history “is by definition immoral: history has no conscience.”5

Another axiom is that in the quest for the future, the individual does not exist. There is no such thing. “We should all guard against uniqueness. It is poisonous.”6 This is explained to the book’s protagonist, Rubashov, by his first interrogator, Ivanov. Not long thereafter, we learn that Ivanov has been murdered, or executed, whichever word seems most appropriate. We experience no emotion at learning of Ivanov’s death. Neither do we experience any emotion for Rubashov’s torment and his eventual death. The book casts a pall of numbness over all its characters. The individual is merely a “mass of one million divided by one million.”7 (It is an oddity that the dictator of this dystopia is referred to as Number One. So there is at least one individual.)

Yet another axiom is that in this soulless environment, there is no place for empathy or compassion.

Rubachov finds himself confronting a question. “What was more honorable, to die in silence or to spit on oneself in public and thereby further the cause?”8 He is convinced that his trial will be his last service to the party.9 His confession of transgressions he did not commit and which were quite absurd is the logical outcome of the illogical logic in the crazy world which exists through the looking glass.

Darkness at Noon was hailed as an anti-Communist book following World War II. It is more than that. It is a description of a world gone mad. In this case, it is the world of the Stalinist Soviet Union. But it could also be a description of Nazi Germany or of the Inquisition. It is a translation of an insane world for the purpose of instructing those of us who are sane.

Why think about this now? Does anyone believe that the craziness described in this book could exist in this country?

The United States is now often described as divided into two worlds, “earth one” and “earth two”. The former is the anti-Trump universe. The latter is composed of Trump and his followers. These two worlds do not communicate. They collide. Trump’s supporters are talking about a post constitution nation. Trump is talking about being a dictator. He says “for one day” but of course that is impossible.10

Where does this remarkable set of circumstances lead the United States? Is it so difficult to believe that we are heading into our own logic of the absurd?

I will return to this question in my next post which will deal with Orwell’s classic 1984. This and Darkness at Noon should be read together.

Andrew S. Grove, Swimming Across: A Memoir (New York: Warner Books, 2001) p. 167.

Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon (New York: Scribner, 2019) p. 168. Footnotes 4 through 9 are from this book.

An interesting essay is Adam Kirsch, “The Desperate Plight behind Darkness at Noon,” The New Yorker, September 23, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/30/the-desperate-plight-behind-darkness-at-noon#:~:text=The%20figure%20Rubashov%20especially%20evokes,he%20gave%20at%20his%20trial

Page 168

Page 136

Page 135

Page 229

Page 112

Page 208

https://sociology.cornell.edu/news/donald-trump-said-hed-be-dictator-one-day-his-supporters-say-theyre-not-worried

Another deeply interesting and disturbing look at a world sinking into a dystopian nightmare.