Chapter Nineteen: The Election of 1864

The Election that Saved a Nation: Lincoln’s 1864 Victory and the Promise of Democracy

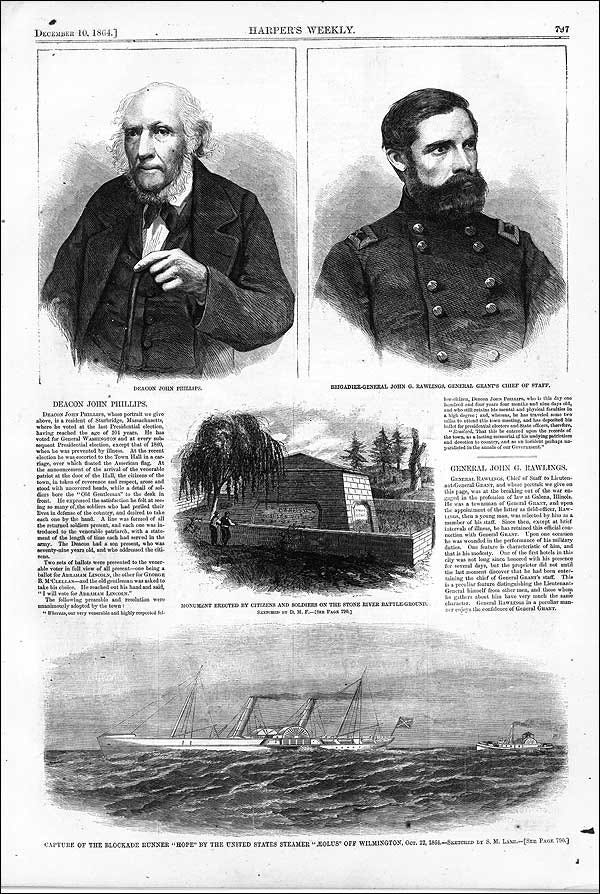

On November 8, 1864, Deacon John Phillips went with his son, Colonel Edward Phillips, to the town hall in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, to cast his vote for President. This does not present itself immediately as a momentous event. But it was.

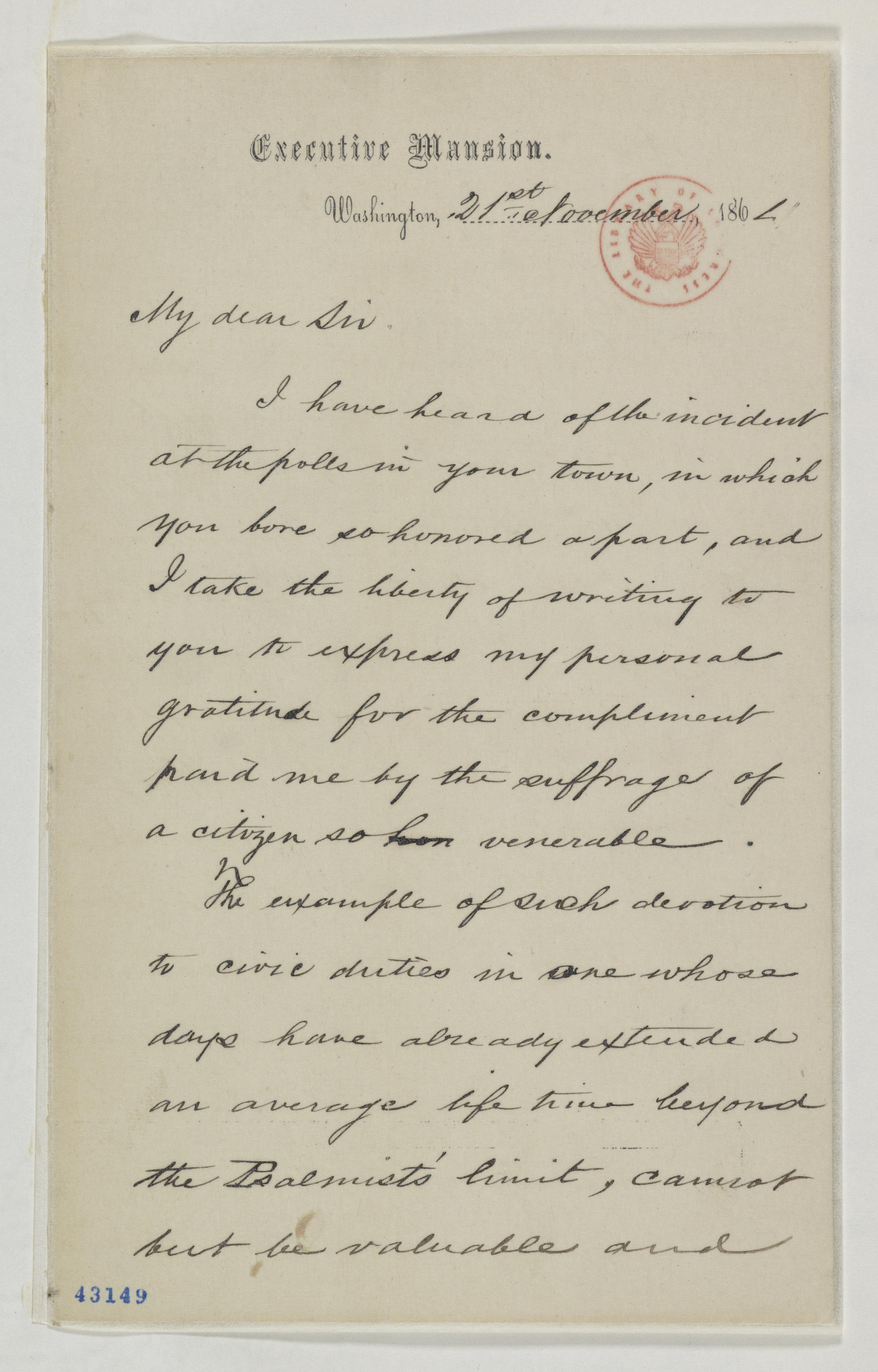

November 8, 1864, was the date on which the Presidential election took place – the Tuesday after the first Monday in the month. John Phillips was 104 years, four months, and nine days of age; and he “still retains his mental and physical faculties in high degree.” He was “an honest, upright, and industrious man, a kind and obliging neighbor, and a good citizen.” Phillips considered himself a Jeffersonian Democrat. But that day, he entered the town hall between “two unfurled national banners” and said for all to hear that he was voting for a Republican: “I will vote for Abraham Lincoln.”1

Phillips’s minister sent word of this event to the White House. In response, Lincoln wrote to Phillips “to express my personal gratitude for the complement paid me by the suffrage of a citizen so venerable. . . . It is not for myself only but for the country which you have in your sphere served so long and so well that I thank you.”2 Deacon Phillips was in all probability the only man in history to have voted for both George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.3

If ever an election were to have been postponed or even cancelled, the contest in 1864 would have been a good bet. The United States was less united – more bitterly divided – than at any time in its history from 1787 down to that day. Not only were the North and South at war with one another, the North itself was questioning whether Lincoln was the man to continue to lead it. By August of that year, the chances of Lincoln’s re-election appeared dim.

The spring of 1864 found the North in a hopeful frame of mind. Great victories had been won the previous year. One of those victories was achieved by Ulysses S. Grant. Grant and his army captured Vicksburg, Mississippi, after a lengthy, strenuous, and creative campaign on July 4, 1863, just a day after the victory at Gettysburg had been achieved. In capturing Vicksburg, Grant split the Confederacy in half by gaining complete Union control of the Mississippi River. As Lincoln observed: “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”4

Following Grant’s victory on the Mississippi, Lincoln moved him to Chattanooga which was besieged by a Confederate army. Grant succeeded in lifting that siege.

On March 2, 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general, a rank previously held only by George Washington. Grant arrived in Washington, DC, on March 8, now in command of all Union armies.

The largest of these armies was the Army of the Potomac. Grant launched his “Overland Campaign” on May 4, 1864. This was the seventh time a Union army set out to capture Richmond.5 “The art of war is simple enough,” Grant said. “Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike at him as hard as you can and as often as you can, and keep moving on.”6

In order to appreciate fully the drama of the months from May to November of 1864, one must keep in mind that events that are now in the past were once in the future. When Grant launched his campaign that May, there were high hopes in the North that the war might speedily be brought to an end.

Those high hopes were dashed. The Overland Campaign developed into battle after battle the toll of which was theretofore scarcely imaginable. From the Wilderness, to Spotsylvania, to Cold Harbor, and finally to Petersburg, in six weeks Grant covered 60 miles and suffered almost 60,000 casualties – “1,000 per mile, 2,000 a day.”7 The losses of the Army of the Potomac were equal to the size of Robert E. Lee’s whole Army of Northern Virginia.8 And what was the result? The siege of Petersburg which lasted from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865.

Thousands of wounded Union soldiers crowded into the 21 hospitals in and around Washington.9 Lincoln was very much the soldiers’ President, visiting the wounded in those hospitals and also visiting the Army of the Potomac in the field. “Look at those fellows,” he said of the wounded. “I cannot bear it. This suffering, this loss of life is dreadful.”10 Lincoln’s law partner in Springfield, Illinois, said of him, “Lincoln is a man of heart – aye, as gentle as a woman’s and as tender.”11 In the words of an historian who was otherwise critical of him, “Lincoln was moved by the wounded and dying men, moved as no one in a position of power can afford to be.”12 “There were moments when he was overwhelmed with sorrow at the appalling loss of life.”13

The summer of 1864 had turned into a nightmare. “There was no good news anywhere. The national debt was approaching $2 billion, an incomprehensible sum. The national credit had sunk to its lowest ebb, and the treasury was nearly empty.”14 As the summer wore on the chances of Lincoln’s being re-elected became dimmer.

As early as February of 1864, Senator Lyman Trumbull observed, “You would be surprised in talking with public men to find how few when you come to get at their real sentiments are for Mr. Lincoln’s election. There is a distrust and fear that he is too undecided and inefficient ever to put down the rebellion.”15 The situation got a lot worse. A very well informed politician told Lincoln in the summer “that his re-election was an impossibility.”16 Numerous such observations could be offered.

By August, “Northern morale sank to its lowest level in the war. Calls for Lincoln to step down in favor of another candidate proliferated.”17 On August 22, the Republican National Committee concluded that Lincoln’s re-election was not possible.18

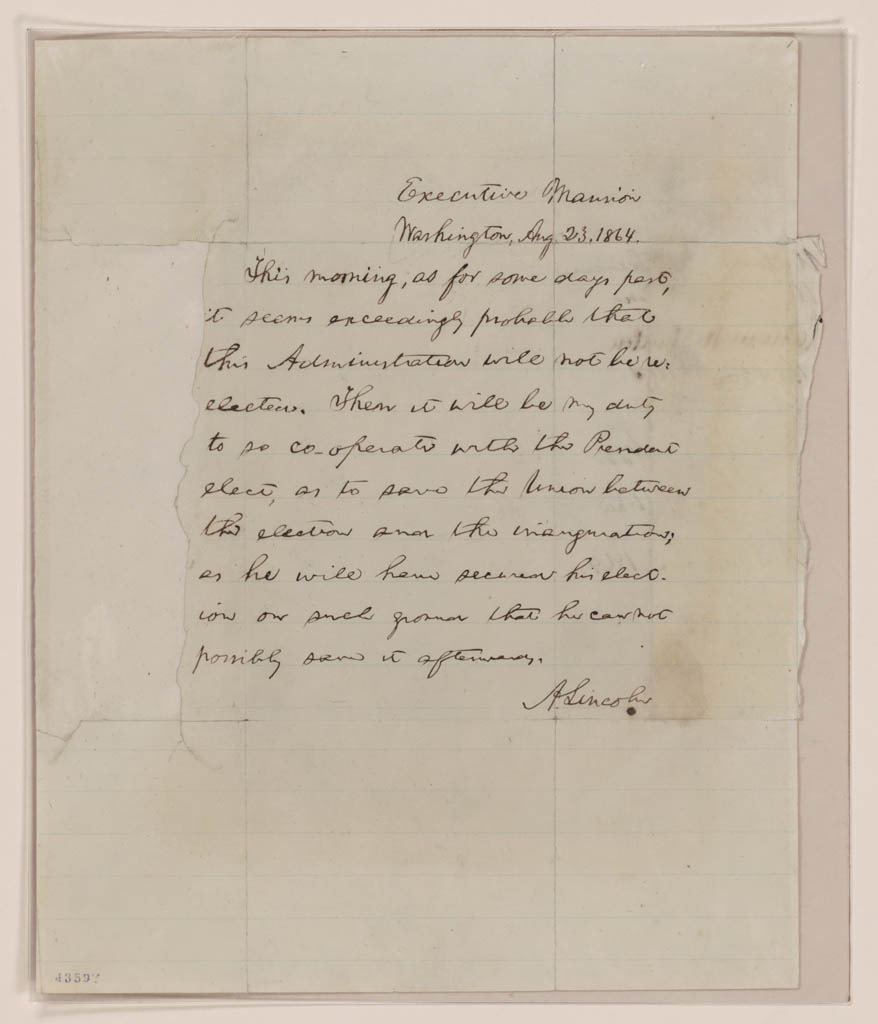

Indeed Lincoln himself, as astute a politician as any in American history, agreed with this assessment. The next day, August 23, he wrote the “blind memorandum” which stated: “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so cooperate with the President-Elect as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterwards. A. Lincoln.”19 (The inauguration in those days took place on March 4 rather than on January 20, as is the custom today.)

Lincoln folded the paper on which this blind memorandum was written so that no one could read it. He then told every member of his cabinet to sign it so that they would all be committed to the course of action he described.

Grant remained stalled before Petersburg, and Atlanta was still holding out against Sherman. On August 31, Lincoln is said to have remarked, “I am a beaten man, unless we can have some great victory.”20 Two days later, Sherman occupied Atlanta. “Atlanta is ours and fairly won”21 was the message he telegraphed to Lincoln the following day. The capture of Atlanta, a key transportation and communication center for the Southeast, was recognized in both the North and the South as a major achievement. Suddenly, it appeared that the tide of the war had at last turned.

It must be emphasized that never once in the terrible summer of 1864 did Lincoln advance the idea that the election should be canceled or even postponed. As he said two days after the election was held, it had been “a necessity. We cannot have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us. . . . It has been demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election, in the midst of a great Civil War. Until now it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility. It shows also how sound, and how strong we still are.”22

The election was not only a triumph because Lincoln won. It was a triumph for what we can call the logistics of democracy. Here is one example. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers were in the field many miles away from their homes. How were their votes to be counted? Prior to 1864 if you did not vote in person in your district, you did not vote at all. The soldiers’ vote turned out to play a key part in Lincoln’s re-election, even though his opponent was a general.

Most important of all, the peaceful and fair election of 1864 was an immense boost to the proposition to which Lincoln had devoted his life. More powerfully than anyone could have imagined a mere four years earlier, the election of 1864 proved that, in Lincoln’s words, “popular government is not an absurdity.”23 To recall the magnificent address at the cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the nation had to highly resolve “that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”24

Nothing less than this very issue confronts the United States today. Will our country have fair and free elections in 2026 and 2028? For the first time in American history a President will be inaugurated who appears not to believe in democracy. Donald Trump has refused to accept the results of the election of 2020. He did not attend the inauguration of his successor.

In 2024, Trump achieved a remarkable victory. Will this turn of events bring him to change his views about democracy? No one knows.

https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Autumn04/phillips.cfm

https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Autumn04/phillips.cfm

My wife, Donna M. Staton, MD,MPH, made this observation.

https://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/conkling.htm

John C. Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln: The Battle for the 1864 Presidency (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2001) Loc. 2291.

Waugh, Lincoln, Loc. 1687.

Waugh, Lincoln, Loc. 2796.

Waugh, Lincoln, Loc. 2804.

Waugh, Lincoln, Loc. 2363.

Waugh, Lincoln, Loc. 2363.

Richard Hofstadter, The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (New York: Vintage, 1989) p. 172.

Hofstadter, Tradition, p. 172.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005) p. 619.

Waugh, Lincoln, Loc. 2806.

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial (New York: Norton, 2010) p. 421.

Goodwin, Team, p. 647.

Foner, Trial, p. 432.

Foner, Trial, p. 434.

https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2014/08/abraham-lincolns-blind-memorandum/

Foner, Trial, p. 437.

https://www.nps.gov/chch/learn/news/so-atlanta-is-ours-and-fairly-won-general-sherman-captures-atlanta.htm

Waugh, Lincoln, Loc. 4964 - 4971.

https://www.neh.gov/about/awards/jefferson-lecture/james-mcpherson-biography#:~:text=%22The%20central%20idea%20pervading%20this,the%20government%20whenever%20they%20choose

Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992).