In this bonus chapter, I am publishing a remarkable essay by Ellen P. Goodman, Distinguished Professor of Law at the Rutgers Law School. Her essay is inspired by Abraham Lincoln’s Lyceum Address, delivered on January 27, 1838, in Springfield Illinois. This address was the subject of Chapter 34, “A Nation in Peril: Lincoln’s Warning,” published on March 18. Professor Goodman’s essay was delivered on March 7th as the “Inaugural Avi Soifer Lecture, University of Hawaii Richardson School of Law.”

As you read this essay here are some points worth keeping in mind:

Our nation needs a culture characterized by respect for the law. “[R]everence for the law is a demand side proposition. The people have to want it.” Culture is difficult to create but, as Trump proves every day, easy to destroy. It requires constant renewal through constant investment.

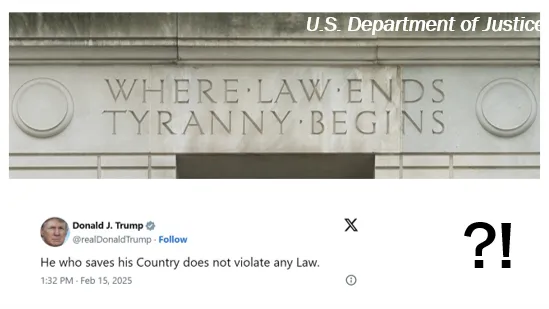

“Where-ever law ends, tyranny begins. . . .” These are the words of John Locke from his Second Treatise on Government. The statement is as true today as it was then. If you want an illustration, the Trump administration recently shipped a man named Abrego Garcia off to a prison in El Salvador “by mistake,” spokespeople claimed. In fact, it wasn’t a mistake. It was the predictable consequence of denying this man due process of law.

“[S]torytelling is at the heart of the matter.” One reason for Trump’s success is that he has a story, and the Democrats do not. Storytelling is important because a story is not (or at least not necessarily) an argument. It can appeal to emotions at least as much as to reason.

Like the “mob” in Lincoln’s day, the Trump Administration “comes for you.” Important American universities are going to find themselves facing what Columbia, Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and Harvard are facing right now. Collective action is essential.

Now let us proceed to Professor Goodman’s Essay:

I was invited to consider for this lecture Lincoln’s 1838 Lyceum Address entitled “The Perpetuation of our Political Institutions.” Everyone will understand the relevance of his great speech that lambastes tyranny, warns of mobs, preaches reverence for rule of law, and worries about the fragility of the American republic. For nearly a decade, lovers of democracy have been anxiously citing Tim Snyder’s On Tyranny and checking off the steps on the slide down. Authoritarian slippage has come to seem more like a lurch as President Trump and his commissars explode all constraints on executive power, issue unconstitutional orders, and pardon January 6 militants, sending the message that violence in service of the leader is acceptable if not welcome.1

I could spend our time together lighting every strand of hair on fire cataloging the demolition of law and the corruption of our political institutions. But you know it already. Mindful of Avi Soifer’s great love of history and his work on Constitutional meaning in service of liberty and equality, I do want to ground this talk in the moment and meaning of Lincoln’s address to his Jacksonian audience. It was a time of roiling violence and lawlessness in American life, when it was not clear — least of all to Lincoln — whether the wildly ambitious and deeply compromised vision of the founders would be buried with them.

Today, as we approach the nation’s 250th birthday next year, we are mindful of how Benjamin Franklin replied when asked in Old City Philadelphia about the form of government the founders had just created: “A republic, …if you can keep it.” Has his skepticism been vindicated? This republic is founded on rule of law, with legal constraint binding up of a diverse and energetic populace. The insurrectionist in the Oval has moved with shock and awe to undo legal constraint. The flex of strength in the face of the law is the point. Legal constraints even where they remain simply cannot scale when a culture of impunity takes hold.

Culture is the subject of this talk, and particularly the transmission of culture through communications. The grip of law and political institutions, the exercise of small “r” republicanism is dependent on a supportive culture — something that Lincoln centers in his Lyceum Address. He alludes to the fact that that reverence for the law is a demand side proposition. The people have to want it. Virtue signaling in our public sphere can be obnoxious, but at least it bespeaks a cultural appreciation for virtue. By contrast, vice signaling — of the kind we saw this week in the joint session of Congress — celebrates a disdain for virtue, maybe that virtue is a sucker’s game. Communications technologies, I suggest, are central to what signals are amplified.

Trump has mastered each medium of communications starting with the tabloids through reality television, talk radio, and social media. It’s possible that each medium has made it harder for our political institutions to function. The rule of law exists, to use Henry Steele Commager’s term, in an “empire of reason.” Reason with a capital R is the centerpiece of Lincoln’s address. It is friend to science, antithetical to arbitrary power and chaos, mother of ordered liberty. Each communications technology promises to enlarge reason’s empire, but each has delivered only fitfully. Today’s media assaults us with what journalist Janus Rose has called “impenetrable nonsense” designed to get us “to post and seethe and doomscroll into the void”, to “overwhelm and paralyze.”2

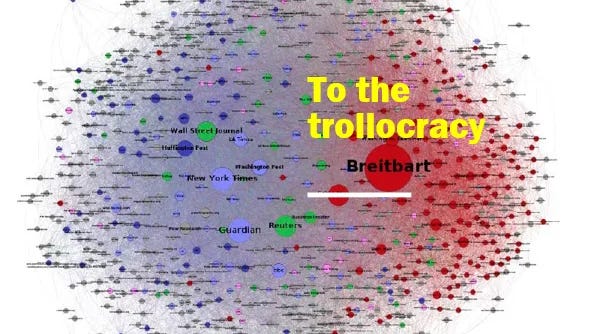

I will start my talk with a look at Lincoln’s Lyceum address and what it says about law, reason, and the mob. The heart of the talk is an argument that the communications technologies President Trump has mastered have increasingly worked to subordinate reason to passion, constructive compromise to performative obstruction, and ordered liberty to “mobocracy,” to use Lincoln’s term. I would add my word to that: “trollocracy.” Policymakers and citizens have always worried about these tendencies and sought ways to mitigate their effects. In fact, government policy can have only marginal impact in a free society. Whether we can nurture a culture that leverages communications technologies to support Reason, is the question I’ll end with.

Part 1. Rule of Law Required

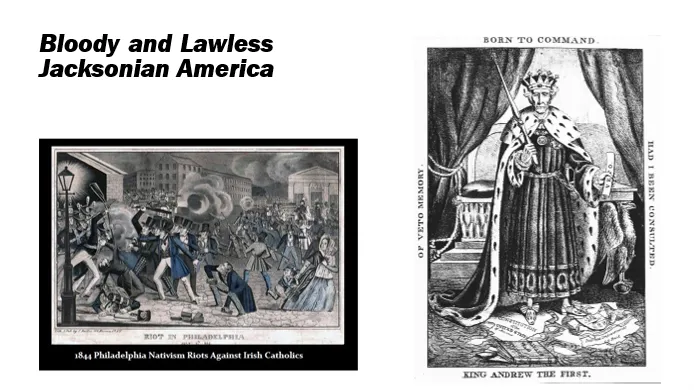

In January of 1838, a 28-year-old Abraham Lincoln took the stage at the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield Illinois. He was a relative newcomer to Springfield in the early days of Van Buren’s presidency, which continued Andrew Jackson’s populist reign.

In the eyes of Lincoln and his fellow Whigs, Andrew Jackson had desecrated the office. He was personally violent, a duelist who had engaged in gunfights and defied the Supreme Court in an extermination campaign against native Americans. Every day, there were street fights animated by ethnic hatreds and lynchings to put down the stirrings of African American liberation. Indeed, the 1830’s were probably the most violent time in American history outside of war.

The gangly lawyer and part time legislator rose to deliver his lecture only a year after the last of the founding fathers had passed away, with the death of James Madison. Lincoln began with a paean to the founders, who he said had bequeathed a legacy of “blessings” and “a political edifice of liberty and equal rights.” How would this generation, fallen as it was, sustain those blessings? From the start, Lincoln was engaging with Franklin’s provocation asking with evident fear how this now orphaned nation would perpetuate the American experiment in self government.

The fear was about “something of ill-omen, amongst us,” by which Lincoln meant “the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country; the growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgment of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive ministers of justice.”

On the minds of the Springfield audience would have been the recent murder in Illinois of Minister Elijah P. Lovejoy, a prominent abolitionist — the first lynching of this kind in the north. The mob had taken it upon themselves, as Lincoln put it, to “shoot editors” and “throw printing presses into rivers.” The leaders of that mob had just been acquitted by — I kid you not — a judge named Lawless.

Historians believe Lincoln’s audience would have had contempt for Lovejoy and agreed with that judgement. So Lincoln elevates two other episodes to make his point about the dangers of a “mobocracy.”

There had been a lynching in St. Louis of a mixed-race man named McIntosh. McIntosh had killed a cop and was awaiting what would probably have been a death sentence. A mob that could not wait for official sanction dragged the man from custody and set him on fire. The other episode concerned murders in Mississippi of gamblers. Describing this mob violence, Lincoln observed the strange fruit of the dead “literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every roadside; and in numbers almost sufficient, to rival the native Spanish moss of the country.”

In telling these stories, Lincoln positions the mob and governmental or legal authority as distinct and contrary forces. Today, corruption of legal authority is happening in collaboration with the mob. A mobocracy need not take the form of people with pitchforks or bear spray. It can be online anons doxing the vulnerable or oppositional, or swarms of bots harassing people, even government officials, into silence. Rewards for intemperance plus virality can bring the physical mob to any place at any time. Think how bar fights and street spats are now content to be captured and monetized, and sometimes used to mobilize. When these techniques of conquest cum performance enter into government — when they influence or become governing tools — the mob merges with legitimate authority. There is then no clear line between a mobocracy and our political institutions.

In his address, Lincoln has 3 things to say about mobocracy:

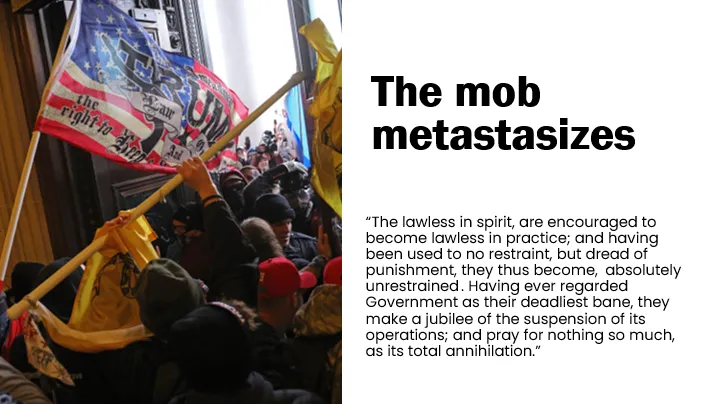

It metastasizes. “The lawless in spirit, are encouraged to become lawless in practice; and having been used to no restraint, but dread of punishment, they thus become, absolutely unrestrained. Having ever regarded Government as their deadliest bane, they make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations; and pray for nothing so much, as its total annihilation.”

Elon Musk’s DOGE is dismantling agencies with gleeful abandon. Musk is a man and not a mob, but he performs DOGE’s every move for his 200 million X followers using the mobocratic tools of inflammatory lies. The historian Quinn Slobodian identifies the anti-government sentiment in the Administration as having 3 sources: traditional anti-New Deal ideology; the private equity tactic of smash and grab; and what he calls “the extremely online world of anarchocapitalism and right-wing accelerationism.” Musk is an exemplar of this last category. The goal is not a smaller government. It is the annihilation of government as we know it, yielding to governance by AI and those who control it.

The mob comes for you. The “mobocratic spirit” is uncontainable. Once it is loose, arbitrary power reaches for everyone. Says Lincoln: “The innocent, those who have ever set their faces against violations of law in every shape, alike with the guilty, fall victims to the ravages of mob law; and thus it goes on, step by step, till all the walls erected for the defense of the persons and property of individuals, are trodden down, and disregarded.”

The American Bar Association has tacitly recognized the mob’s omnivorousness in its unusual letter standing up for the rule of law. Whatever your views on particular policies, it wrote, “no one wants their neighbor of family to be treated this way” — meaning subject to arbitrary exercises of power. Trump voters who have been summarily fired have found out the hard way that walls breached fall on them too.

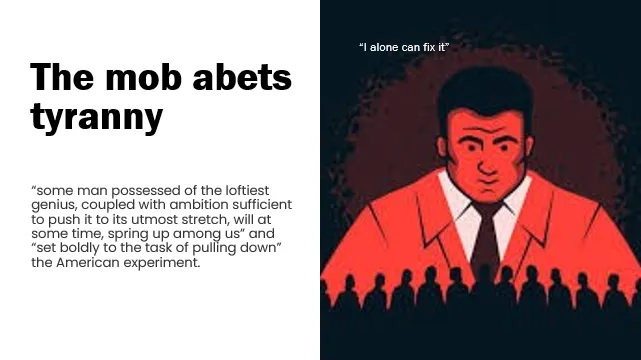

3. The mob abets tyranny.

In Lincoln’s telling, the mobocratic spirit sets itself against government capacity. When government is no match for the mob, and destructive passions are unleashed, a tyrant will arise to offer order. This will be “some man possessed of the loftiest genius, coupled with ambition sufficient to push it to its utmost stretch” for whom the difference between doing good and harm is as nothing, so long as the doing brings “distinction.”

Today, we’re seeing that the mobocratic spirit can partner with tyranny, not just precipitate it. Those who question the propriety of what Musk or others in the Trump Administration are doing, whether they are judges, elected officials, or bureaucrats, risk being harassed by online mobs or the government itself. This threat secures obedience perhaps not less than official sanction.

Concern over the mobocratic spirit is not isolated to the political Left. In his year-end report on the federal judiciary, Chief Justice Roberts expressed alarm about the threats facing federal judges. He noted that “the volume of hostile threats and communications directed at judges has more than tripled over the past decade.”3 In the past five years alone, federal marshals “report that they have investigated more than 1,000 serious threats against federal judges.” The Chief Justice goes on to blame doxing, social media mis and disinformation, and foreign campaigns — sounding very much like critics on the Left. He complains of agents feeding “false information into the marketplace of ideas. For example, bots distort judicial decisions, using fake or exaggerated narratives to foment discord within our democracy.” He went on to write that “we must as a Nation publicize the risks and take all appropriate measures to stop them” for the sake of public confidence in judicial “processes and outcomes.”

What to do about the mob? Is it already too late? For Lincoln, the answer is upstream of politics. He prescribed that “the people” must “be united with each other, attached to the government and laws, and generally intelligent, to successfully frustrate [the tyrant’s] designs.” In Lincoln’s view, the only way to combat tyranny is to make reverence for the rule of law the civic creed.

Sanford Levinson, in his book Constitutional Faith, observes how this call was taken up in post-bellum America and animated the reborn nation. The creed lives on in the oaths that federal officers take to the constitutional order. Oaths and reverence surely meant something different in an America that treated oaths as sacred acts. And still we see today how many courageous feds are asserting the primacy of those oaths.

As every autocrat will tell you, rule of law and respect for political institutions are rather malleable phrases.

Avi Soifer pointed out to me that Rule of Law is an anagram for Awful Lore. Lincoln’s assassin thought that HE was the tyrant. After all, he had suspended habeas corpus, which most experts at the time and later did not think was within the President’s power. He censored the telegraph and imprisoned journalists in his prosecution of the Civil War. Lincoln has been hero to repressive as well as liberatory leaders. Opponents of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960’s leaned on the Lyceum speech to push against “lawless” civil disobedience.4 In 1966, for example, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley quoted Lincoln in an effort to quell civil rights protesters. Earlier, Senator Joseph McCarthy had quoted the Lyceum Address’ warning about domestic threats as support for his anti-Communist crusade. We can acknowledge that Lincoln himself had a complicated relationship with the law… all to end up ushering in a new and better constitution. Who knows, maybe we have before us constitutional amendments and new births of freedom. Let us pray.

Lincoln closed his address with an elegiacal salute to the founders’ revolutionary passion. That passion did its work in the founding era, he says, but “it will in future be our enemy.” In place of the mob’s passion, Lincoln says “cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason” will defend the Republic.

Appetite for and ability to reason would have to be inculcated, parented, educated into the citizenry. Let reverence for law, Lincoln says “be breathed by every American mother, to the lisping babe… — let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges…let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice.”

All this teaching and preaching builds demand for rule of law and attendant democratic deliberation. Good governance is downstream of culture. It’s notable that Lincoln gives this speech in a local voluntary association designed to foster learning and participation — the sort of place that delighted Alexis de Tocqueville. In his Democracy in America (also from the 1830’s), he wrote that such associations cultivated the practice of democracy for the American who plunges “into the wilderness of the New World with his Bible, a hatchet, and newspapers.”

Part 2. The Demand-Side Problem

Few would say that TikTok, X, BlueSky, YouTube, or Facebook are fostering an empire of reason. These platforms follow on predecessor technologies, each of which has worried critics that it would unfit the population for democratic self rule, or to use Lincoln’s language, that it would supplant reason with passion. And with each new technology, citizens and their representatives have tried to better align it with the requirements of a democratic republic. Notwithstanding these interventions, there really has never been the will or institutional commitment to support the cultural project Lincoln imagined.

Far from bathing us in cool reason, our communications systems evolved to promote ever hotter and more inflammatory exchanges of information. It has become easy to activate and assemble mobs, even if only on screens that average (depending on your demographic) 4–6 hours of daily attention. Social media pair hot takes with data-driven personalized messaging and addictive design to hack and “frack” attention.5 The frayed quality and polarized directions of our attention make it hard to imagine even a shared language around terms like “rule of law” or “political institutions.”

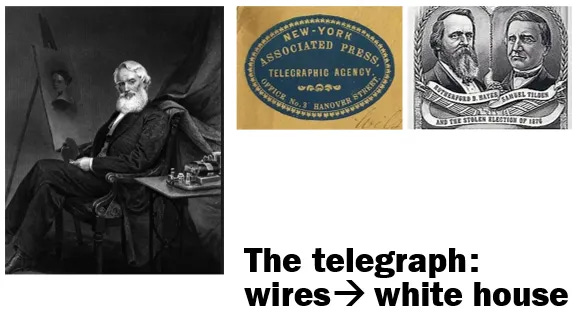

How did we get here? We might as well start with the year of the Lyceum speech, for it was in 1838 that Samuel Morse brought the telegraph to the U.S. Capitol in hopes of securing Congressional funding to develop the new technology.

Morse acknowledged that the telegraph — like most technologies — was multivalent. In a letter to the Chairman of the House Commerce Committee, he wrote: “This mode of instantaneous communication must inevitably become an instrument of immense power, to be wielded for good or for evil, as it shall be properly or improperly directed.”

While Unionists initially thought the telegraph would bind the nation together, they soon discovered it exacerbated sectional tensions. Richard John in his book Network Nation, quotes a Unionist calling the telegraph a “’treacher’” which sends an “‘electric thrill of panic’” every hour after the transmission “of misleading news reports to the home front that had been sent by irresponsible journalists from the theater of war.” (108).

Western Union allied itself with the Associated Press — both monopolies in their domains — to furnish newspapers with news of the day. Between the two of them, they controlled the news and could also read private messages. Sort of like a digital platform can control a newsfeed and DMs.

In the razor thin Presidential Election of 1876, Western Union backed Rutherford Hayes. Apparently, Republican Hayes was losing to Democrat Tilden when the telegraph company provided Hayes with internal messages from Tilden’s campaign, helping Hayes to re-orient his efforts. Tim Wu in his book The Master Switch holds up this event as an example of how power over communications networks can confer political advantage — we might say it’s a synergy of tyranny.com and tyranny.gov.

The federal government would eventually regulate the telegraph as a common carrier to mitigate the effects of monopoly. On the newswire end, it wasn’t until 1945 in AP v. United States that the Supreme Court reined in AP for antitrust violations. Justice Black wrote one of the defining aspirations of American free speech jurisprudence in that case: what was necessary for a “free society” was to promote “the widest dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources.” Cracking open tyranny.com was a way of preventing tyranny.gov.

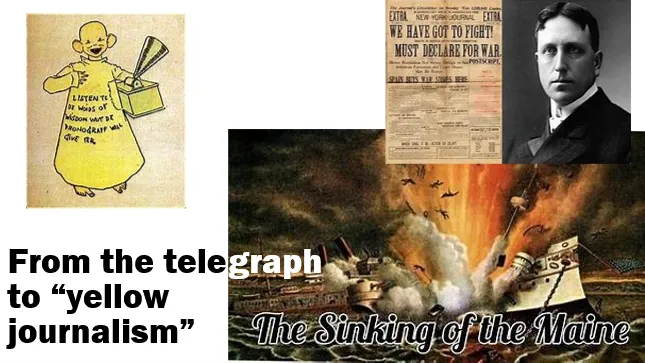

Diverse and antagonistic voices include nonsense. The telegraph was a principal driver at the end of the 19th century of yellow journalism, named after this little yellow man cartoon.

Rival news magnates Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst both used it, competing with each other in newspapers throughout the country with sensational false or unverified stories. Hearst was very much in favor of the U.S. going to war against Spain in the Caribbean.

So he transmitted conspiracies blaming the Spanish for blowing up the SS Maine to enflame the public. Fake news was nothing new. John Adams complained of it bitterly. What was new was the use of nationwide economic power to propagate lies. Yellow journalism coincided with a period of repeated economic shocks, monopoly growth, government corruption, mob violence in the Jim Crow south, and attacks against immigrants in the fast-industrializing north.

Reformers trained their eyes on media.

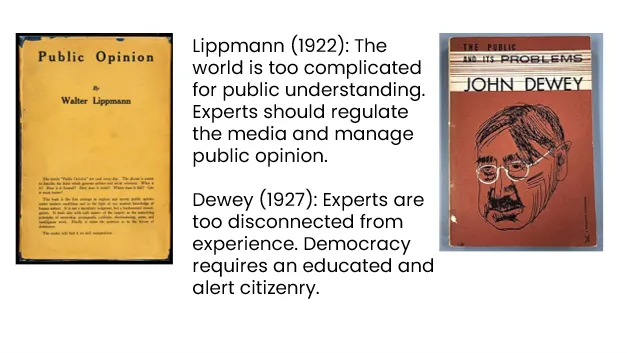

By the 1920’s, the media advertising model was mature and Edward Bernays, nephew of Sigmund Freud, published his pioneering work Propaganda on how to exploit human irrationality to sell cigarettes and politics. Accelerating social change stoked anxieties about democratic governance.

Walter Lippmann despaired of the public’s ability to manage their political affairs and favored heavy elite intermediation. Newspapers, he thought, should be subjected to technocratic control to ensure that people received carefully curated information.

John Dewey, took a different view, more aligned with Justice Black’s. People could be trusted to overcome their irrationality and low quality information, if only they had more civics and media literacy. This debate between elite direction, and bottom-up muddling through — albeit under the tutelage of the virtuous — continued to shape media policy over the next century.

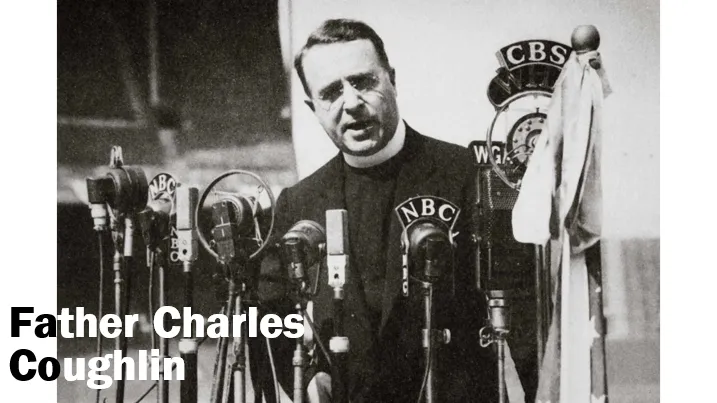

By the 1930’s, with the spread of radio broadcasting, “yellow journalism” was more compelling as it streamed into people’s living rooms. This time, America Firsters were antiwar and the messaging viciously antisemitic and pro-fascist. Father Charles Coughlin reached about 1 in 3 Americans by the end of the decade (30 million). When he blamed Kristallnacht on its Jewish victims, some of the radio stations that had carried his sermons took a step back.

Major networks like NBC and CBS decided to ban paid political and religious programming altogether for a time, presaging the move of digital platforms in the 2020’s to experiment with deplatforming and selective algorithmic promotion. The “vibe shift” against Coughlin’s incitement in the 1930’s had much more effect, both because of the control broadcasters exercised and because of the regulatory pressure the newly constituted FCC (1934) could bring to bear.

The vibe turned decidedly after WWII. At least among elites, there was a return to something a little like Lincoln’s rhetoric. Having escaped the fascist and communist waves that swept Europe, the United States, it was argued, needed to set its sights on demand-side democracy. Communications again were a central part of this project.

Looking back, people understood the important role radio had played in promoting Hitler and his project in Germany. In the U.S., in addition to the Coughlin scourge, there was a hoax radio broadcast in 1938 that scared the bejesus out of Americans. Orson Welles had broadcast on CBS radio a fake play-by-play of a Martian invasion. It was so realistic and alarming as to sew panic among thousands of listeners. The government noted broadcasting’s power to make worlds and shape reactions. Seeing this, Henry Luce, CEO of the great Time-Life media empire, thought industry should get out ahead of possible regulation.

He sponsored a Commission of leading intellectuals, chaired by University of Chicago President Hutchins, to figure out what media should look like in the post-war era.

One of my mentors, the late legal scholar C. Edwin Baker wrote in 2007 that the Hutchins Commission report is ‘‘the most important, semiofficial, policy-oriented study of the mass media in U.S. history.’’

It articulated the social responsibility theory of the press which goes something like this: self-government requires a press that acts as the 4th Estate, independent from government, and committed to the service of truth. Very much echoing Lincoln’s prescription of cool reason, the Hutchins Commission imagined a press that provided dispassionate information without fear or favor in service of a self-governing citizenry. To fulfil this function, the press itself would have to exercise republican virtues and self-restraint in its own sphere.

Breaking the Watergate story and associated corruptions in the 1970’s might have marked peak social responsibility press. These were the years that produced lawyers like our honoree Avi Soifer and our sponsor Reed Hundt. The social responsibility press, like many liberal commitments, posits the possibility of operating outside of politics and passion. It imagines that White House reports can collaborate on a press pool for basic facts, for example. That there is a distinction between fact and opinion is central not only to this conception of journalism, but also to law and democratic governance. When the White House exerts control over the press pool and shuns “unfriendlies,” it is attacking that basic distinction.

In any case, by the 1970’s, Americans’ attention was migrating to television entertainment.

FCC Chairman Newton Minow famously had warned in 1961 that much of television was a “vast wasteland.”6 He was focused on banal content. When the media scholar Marshall McLuhan wrote in 1964 that the “medium is the message,” he was arguing that content didn’t matter that much. More important for culture were the technical affordances of media and the ways in which they related to our rational faculties. Using Lincoln’s temperature metaphor, [and borrowing from the socialist Claude Levi Strauss,] McLuhan divided media into hot and cool. Hot media demanded from us little cognitive work or reason. Cool media asked us to participate in the construction of meaning. Weirdly, he thought TV was a cool medium.

Not so one of his students, Neil Postman. In his book Amusing Ourselves to Death, which is 40 years old this year, Postman essentially predicts the way someone like Trump will use a hot medium to take control. Very much in keeping with Lincoln’s Lyceum forecast, he writes that America will be conquered from within. “People will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think… what we love will ruin us.”

With nostalgia for a past era of patient discourse around oratory and print, Postman dates the decay to the telegraph, which created “a neighborhood of strangers and pointless quantity; a world of fragments and discontinuities.”7 Historian Daniel Boorstin observed that television encouraged the production of “pseudo events” or meaningless happenings imbued with fake significance. Postman used the term “disinformation” not to mean intentionally false, but maybe something worse: beside the point, distracting, numbing.

Ultimately, Postman wrote, TV creates a “culture overwhelmed by irrelevance, incoherence, and impotence.”8 One of his most incisive observations was that TV collapsed context, presenting events immediate and faraway, relevant and irrelevant, grave and trivial in a single flickering stream of images that discouraged discerning engagement.

These were President Reagan’s 1980’s and the spirit was deregulatory. These were Donald Trump’s 1980’s and the bywords were go-go and greed. These were the early days of an expansion of TV options with Fox, talk radio, and then cable channels. If there was a policy response to concerns about TV’s impact on democracy, it was to foster competition.

There continued to be tepid support for the Great Society project of public broadcasting. Ambitious in goals, if not in funding, the creation of a noncommercial broadcast network was responsive to another blue ribbon commission of luminaries, the Carnegie Commission. To this body, the author E.B. White had written that TV should “address itself to the ideal of excellence” through programs that “arouse our dreams” and a system of local stations capable of becoming — wait for it — “our Lyceum, our Chautauqua, . . . and our Camelot.”9 The hope was that hundreds of local stations spread out across the country from small towns and farm communities to big cities would produce programming and also convene in person public discourse. Reasoned inquiry — if not cold reason — was a core value.

One thing local and national public media always did well was to platform new voices and formats left out of the mainstream. Here we got the first reality television programming which would serve Donald Trump so well. Big bird and kids TV, science and documentary programming, and even some conservatives had their beginnings here. However much public and burgeoning commercial media might have advanced Justice Black’s ideal of diverse and antagonistic voices, this was nothing compared to what the early internet birthed.

There are few people who know more about the 1996 Telecommunications Act than Reed Hundt, who as FCC Chairman was responsible for implementing it. Some combination of DARPA investments, Tim Berners-Lee, and the Act made the internet. Law fostered infrastructure development and liability shelters for digital intermediaries. When signing the law, President Clinton made a comment similar to what had been said on Capitol Hill about the telegraph. “We know the Information Age will bring blessings for our people and our country. But like most human blessings, we know the blessings will be mixed.” Like the Unionists, Clinton imagined the Information Superhighway would bring Americans together. “That same spirit of connection and communication is the driving force behind” this law. And with that, he handed the pen to the Information Superhighway’s champion, Al Gore, whose father, Senator Al Gore Sr., had sponsored the Interstate Highway Act.

The decade or so that followed was filled with tech optimism for what Douglas Rushkoff called “open source democracy” (2003). This was the Dewey dream: that internet-enabled communication and decentralization would advance democratic self rule. I never quite shared that optimism. I was more inclined to trust those like Evgeny Morozov who in 2011 in his book Net Delusion warned that autocrats and oligarchs would figure out how to capitalize on the technology. As soon as tech companies figured out how to build platforms that would engage people in a mostly passive media experience, the industry consolidated the telegraph’s one-to-one communication with the broadcaster’s reach. Add to that network effects and algorithms that enclosed people in particular corporate architectures, and the decentralized web of the early aughts was gone.

The Supreme Court last term in Moody v. Netchoice continued to refer to social media platforms as the “modern public square,”10 gesturing towards that Dewey ideal. So it is that. But it sunders apart as much as it convenes. If television proved to be a fiery medium, social media communications are an inferno.

The social science around what exactly social media has done to our discourse and reasoning continues to evolve. Recent studies seem to confirm McLuhan’s insight that the technological affordances are most important. These include the tenor, speed, and amplification of content, as well as the mobilization of radicals and incentives for bad behavior. These features hack our attention in ways that undermine cool reason and abet mobocracy. I’m not suggesting that communications and culture alone explain our current moment. But it’s hard not to see that Trump, Musk, and those around them have turned internet “trolling” culture into a governance agenda. It is a trollocracy.

I’ll focus on three social media design features: (1) incentives; (2) amplification; and (3) mobs.

Memes, Rage, Trolling & LULZ

If it once took significant investments from Orson Welles and CBS radio to fool the nation into believing it was under attack, digital media makes it trivially easy to concoct and spread lies that seem realistic, especially among those inclined to believe them. Viral content is more likely to be low quality, unverified, or flat out false. Postman noted “context collapse” in TV. It’s so much worse online with bits of audio or video flying around untethered to any context. Editorial standards, fact checking, and distinctions between news and opinion are simply not rewarded or even understood. Boorstin’s pseudo-events now constitute much of our politics with electeds and constituents alike performing for likes and shares.

As with previous technologies, the affordances of social media are multi-valent. One of the delights is meme culture. These visual jokes can wonderfully make light of and defuse difficult subjects. They can also swiftly convert subversive chuckles into radical positions. The new right has perfected the use of memes, “just joking,” and in it for the LULZ to valorize political violence, Nazi salutes, and violence against women and other “out groups.” Is it just a joke? Just Edgelord trolling? The media scholar Joan Donovan’s work on Meme Wars documents how memes and viral rage led the militia curious to pitchforks on January 6.

Trump is a master of meme culture. When he posts from the official White House site a picture of King Trump wearing a crown, he’s “just joking.” Or not. Not for nothing, Musk named DOGE after layers of memes: a meme coin named for an older meme of a Sheba Inu dog with broken English. Reverence for the rule of law requires first of all a sense of reverence. There are no sacred cows in meme culture. It is revolutionary or reactionary, but never reverent.

Algorithms and Data

Algorithmic amplification further intensifies angry communication. Leveraging personal data, platform recommender systems and feeds direct hot rhetoric to willing consumers. With this architecture, it is no wonder that the work of government becomes bite-sized rage performances. The Hutchins and Carnegie Commissions believed that communications companies should support self- governance. That might mean fair and serious news coverage or helping local communities to cohere. In the digital world, the entities with that power are the platform designers. They do not feel much responsibility, and in the past few months have been completely liberated from any vestige of the responsibility they did assume.

Rule of law ultimately relies on widespread acceptance of the legitimacy of the law. It relies on people accepting a sphere of neutrality in which equal application of the law is possible. Our digital platforms — by virtue of the power of influencers and algorithms — flood us with repeated assertions that things are not on the level. With context collapsed, you will easily see that the “other side” or “those people” are crooked. What you’ve been told is not true. If you believed in neutral principles, you were a sucker. These narratives spin out on both Left and Right: in the form of populist attacks on institutional authority and expertise, rejection of fair journalism, and illiberal ideologies. The result is an environment in which reasoned compromise gives way to zero-sum power struggle.

Pile Ons and Mobs

The last feature of social media brings us back most clearly to Lincoln’s fears. We love to feel that we are part of a tribe; that we are empowered to take action. The ability to rouse a following to a cause, and to join that cause, is one of the delicious affordances of social media. It’s what fueled the Iranian Twitter revolution in Iran in 2010 and the Ukrainian Maidan revolution in 2014. Distinguishing a protest from a mob shouldn’t depend on whose side you’re on. As Lincoln used the word, mobs usurped the state’s legitimate monopoly on force. Online mobs rarely go this far, but they sometimes do. Just ask the Sandy Hook families. And they frequently threaten to. At the very least, for most people, being harassed, doxed, and lied about will quickly silence their diverse and antagonistic voices.

In his first administration, Trump brought the online pile into the White House, calling out particular people for MAGA harassment. Those practices are now much more widespread. Lawmakers fear that mobs will be directed to their houses, as Justice Roberts was afraid for his colleagues. We can only wonder whether online mob culture has softened the ground for mob actions in the government. Uncredentialed DOGE functionaries exercising illegitimate authority is arbitrary power — cousin to the mob.

Conclusion

Let me take you back to the Lyceum Address as we close. One of the rhetorical moves Lincoln makes in his Address is to tell the stories of the mob twice: once in a way that makes the victims of mob violence sympathetic and once much less so. For example, in the second telling, he says the Mississippi gamblers were “worse than useless in any community” like “plague or small pox.” By doing this, he’s challenging his audience to distinguish policy from process. Even if you agree with the policy outcomes of the mob, you surely can’t condone the lawless process. This is what the ABA was saying in its letter. Patience is required for rule of law. The mob that lynched McIntosh could not wait for justice. And this is why the Trump Administration does not use its compliant Congress to pass laws. It uses the tools and temperament of the mob, and the troll.

Where rule of law requires patience, our communications privilege immediacy. Where ordered liberty makes distinctions between proof and conjecture, political and legal, gangster and government, our communications collapse categories and context. This collapse then manifests in Washington D.C.

Dorothy Thompson wrote in 1938 just after Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast: “The greatest organizers of mass hysterias and mass delusions today are states using the radio to excite terrors, incite hatreds, inflame masses, … abolish reason and maintain themselves in power.” (Jill Lepore, These Truths, 470). What Welles had done was just performance art. The real threat is the fascist use of media. When government itself is the performer capitalizing on mass hysteria and delusions, a democratic culture must resist.

I wish I had a list of 10 correctives for our media culture, something like Tim Snyder’s list in reverse. There are a lot of good design ideas out there about how to build better social media, how to reduce the control of algorithms and the logic of big tech, how to cultivate better information sharing hygiene and literacy especially in the AI age. Some of these involve law and policy, but this seems hardly the moment.

There are also good ideas that are much older than that, about building democratic culture in real places like the Lyceum.

In the early 19th c, there were 3000 Lyceums scattered in towns across a much smaller U.S. There’s a movement now to bring them back. Touch grass. Whatever the distribution method, we should take seriously the demand side of rule of law and reasoned discourse. As Lincoln knew, storytelling is at the heart of the matter. Lincoln’s lessons that the mob metastasizes, it comes for you, and it abets tyranny all have to be brought home in actual stories. These are stories about the corrupt prosecution, the shuttered federal service, the crooked contract diffused through every medium and using all affordances. That used to be the job of journalists, and it still is, but it’s the job now of everyone.

https://ellgood.medium.com/tyranny-com-technologies-of-unreason-f0a1feede076#_ftn1

https://www.404media.co/you-cant-post-your-way-out-of-fascism/

https://www.uscourts.gov/data-news/judiciary-news/2024/12/31/chief-justice-roberts-issues-2024-year-end-report

https://www.friendsofthelincolncollection.org/lincoln-lore/6804/

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/24/opinion/attention-economy-education.html

http://television%20and%20the%20public%20interest/

Postman, Neil. Amusing Ourselves to Death, p. 70.

Postman, Amusing, p. 76.

https://current.org/1966/09/e-b-whites-letter-to-carnegie-i-2/

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/603/22-277/