Since ancient times, people have speculated about what makes the best achievable society. In 1516, Sir Thomas More endowed this goal with a name – utopia. This name “has become synonymous with paradise [and] the ideal” but also with “the unrealistic and unattainable.” The name itself is a pun on two words which mean “good place” and “no place.”1

Dystopia is the opposite of utopia. Dystopia is characterized by fear, a realm “where chaos and ruin prevail.” It is usually “identified with the failed utopia of twentieth-century totalitarianism,” regimes “defined by extreme coercion, inequality, imprisonment, and slavery.”2

Why study dystopia? Because it shines a light on its opposite, utopia. Because it shows what transpires when people in groups do what they as individuals would never have countenanced. Because it shows the extremes to which people will travel on the wrong road. Because it illustrates the logic of the absurd. Because it shows the danger of confusing means and ends. Because it shows how vital – how precious – is the commitment to truth.

Dystopia is worthy of study because it provides a warning.

Utopia and dystopia are uncomfortable bedfellows. History shows that the quest for the former can produce the latter. There is no better case in point than one of the defining episodes of the modern age, the French Revolution (1789 – 1799).

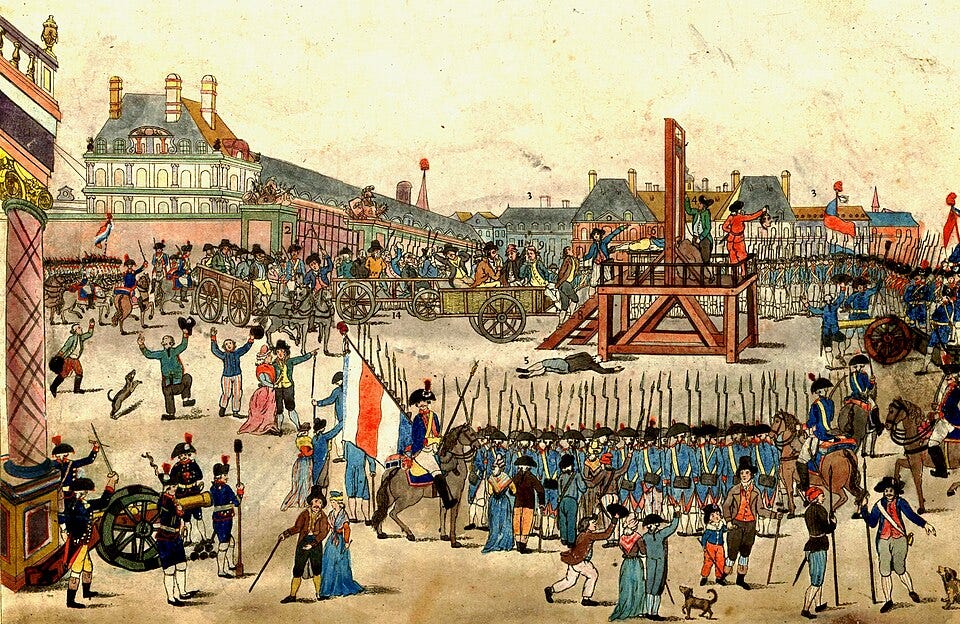

The Revolution began with a burst of optimism and a hope for a future characterized by the famed trio of goals - liberté, égalité, fraternité. However, soon after the revolution began, the Reign of Terror commenced. It lasted for about a year beginning in the summer of 1793. Terror won a place “on the order of the day.”3

In the words of Maximilien Robespierre, “Virtue without terror is powerless.”4

The slaughter which the year of the Terror witnessed was horrifying in its intensity and its sadism. Fear was omnipresent. The guillotine became the symbol of the new order. When one reads accounts of the “holocaust for liberty”5 – a phrase literally used at the time – it is amazing that anyone at all survived in France.

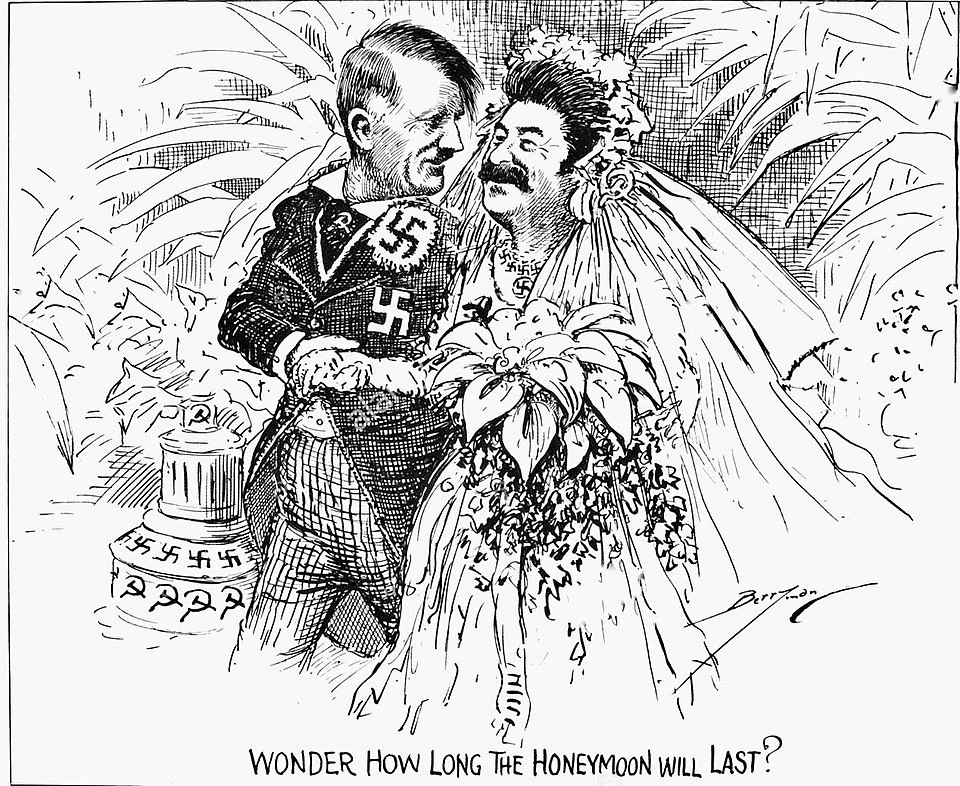

That phrase – “holocaust for liberty” – is important in the history of dystopia. Dystopian regimes often confuse means and ends. The ends seem so desirable that the means by which they are achieved can easily fade into irrelevance. How important are the deaths of a couple of hundred people or of a couple of million people if that is the price for the achievement of heaven on earth? The dilemma is that we are never going to reach utopia. Hitler promised Germany a thousand-year Reich. It lasted for 12 years. The communist revolution in the Soviet Union promised its citizens and the world an environment in which all were comrades, and theft disappeared because no one owned property. The reality under Stalin could not have been farther from this goal. Since utopian goals are never reached -- the ends are never achieved -- we live in a world of means. Means become ends.6 Liberty for everyone will never be achieved. Holocausts, by contrast, are all too familiar.

Hitler and Stalin were the monsters of twentieth-century terror, creators of the two most well known dystopias of their era. They learned well the lessons of the Terror during the French Revolution and indeed of the Inquisition centuries before it. (As a youth, Stalin was a student in a seminary in his native Georgia in 1894.)

The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917 had its own version of the famed trio liberté, egalité, fraternité. For the Russian revolutionaries, the three goals were “peace, land, bread.” And eventually a new freedom in a new world. What was delivered was a ministry of fear rivaled only by Hitler.

Worship of the leader, thought control through unending propaganda, random violence, torture, the omnipresent war on truth – such was the life of the Soviet Union under Stalin. “Abandon every hope, you who enter.”7 Those were the words Dante saw as he began his descent into the Inferno. Likewise, a well-known book about life under Stalin is entitled Hope Abandoned.8

Stalin’s regime in the Soviet Union illustrates dystopia in action. “Thirty-five agronomists were shot in 1933 for causing weeds to grow. Members of the meteorological corps were arrested for predicting weather harmful to crops. . . . A mentally ill, deaf-mute who could not even sign [got] 10 years for counterrevolutionary propaganda. . . .” A member of the Academy of Sciences was informed that the fact that “you may be innocent does not play a role. If you are arrested, we will find you guilty of something. . . .” After all, everyone is guilty of something. Indeed, the very act of getting arrested rendered the prisoner dangerous because he now understood “how rotten the system was.”9

This may sound humorous, but it is not. Those responsible for the 1939 census in the Soviet Union were executed because they reported a decline in population. Their replacements reported an increase in population. This was inaccurate, but it was what the leader wanted to hear.10

Dystopian fiction has a role to play in decoding this kind of craziness. That is why Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon11 is such an important book. The standard by which all dystopian fiction will forever be judged is George Orwell’s 1984.12 The power of 1984 is that elements of Orwell’s dystopia are alive with us today.

Dystopias apparently have slogans that come in threes. This is what is on offer from 1984: “War Is Peace; Freedom Is Slavery; Ignorance Is Strength.”13 Here is an interesting interpretation of these slogans by an authoritative scholar. I do not agree with it, but I offer it for what it may be worth. “[T]he pretense of constant war insures domestic peace insofar as the Party’s rule is not threatened; . . . The ‘free’ epic prior to party rule had been one of working-class enslavement by capitalists; and . . . knowledge of the truth would weaken the regime, . . so ignorance. . . props it up”.14

The problem with this noteworthy interpretation is that it tries to make sense out of something which is purposely senseless. These slogans are a demonstration of power. The three statements are true if the dictator of the 1984 dystopia says they are true. The Party can make you believe a lie, because the Party’s endorsement transforms every lie into a faux truth.

“Freedom,” observes the protagonist of 1984, Winston Smith, “is the freedom to say that two plus two make four.”15 But the Party would eventually assert “that two and two make five and you would have to believe it [because] . . . . The heresy of heresy was common sense.” At the end of the book, a defeated Smith gives in. “2 + 2 = 5.” There is no “external reality.”16 Reality is what the Party says it is.

1984 is the best illustration of how dystopian fiction can serve as a warning. Look at the United States today in the era of Trump. The lies are constant, sometimes as ridiculous and as exhausting as those in 1984 or in the Stalinist USSR. War was continuous in 1984 because a sense of emergency was good for the Party. Since January 20, Trump has ruled by emergency decree. There are no emergencies other than the ones he has been causing. This is the world of 1984 in action.

Here are two illustrations of the assault on truth - lies a la 1984 - Trump has been mounting.

On June 22, the United States bombed Iran, a nation by the way which had done us no harm and was not a threat. This was an unConstitutional use of force by Trump, but that is how the administration has been conducting itself. Trump immediately boasted that Iran’s three main nuclear sites had been “completely and totally obliterated.”17 However, a report from the Defense Intelligence Agency held that Iran’s nuclear program had only been set back by months. An angry Trump immediately attacked not the facts but the messengers. He accused Democrats of leaking the intelligence report and asserted that "they should be prosecuted.”18

When the dear leader speaks, his underlings know that they better agree and do so quickly. Immediately, Vice President JD Vance, Secretary of State Marco Rubio, CIA Director John Ratcliffe, and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth all fell into line, asserting with geometric certainty what could not be known and was at least doubtful.19 But if Trump says 2+2 = 5, it is your job to agree.

Other administrations have lied. We have just endured numerous Democrats proclaiming the competence of a seriously disabled Joe Biden. But the lying in this administration is omnipresent, and its implications are dangerous. “Tailoring assessments to suit political prejudice undermines their very function and led us to the Iraq war.”20

Privileging the Trump party line suffuses the federal government. For example, a few days ago there was a meeting of the newly constituted Advisory Committee on Immunization Policies. This new committee was put together by the calamitously unqualified Bobby Kennedy, Secretary of Health and Human Services. Some members lacked vaccine expertise. These people “questioned basic epidemiological methods [and] misunderstood fundamental scientific principles.” This is “absolutely unacceptable for people determining vaccine policy” for every American. “[M]any committee members clearly began with conclusions and then attempted to force the evidence to fit. This is called policy-based evidence-making not evidence-based policy-making. It’s backwards.”21

And it is backwards precisely the same way the reports of the attack on Iran are backwards. Policy-based evidence rather than evidence-based policy. This is one of the defining features of our dystopia in the era of Trump.

2 + 2 = 5. The fundamental equation of Trumpworld.

Gregory Claeys, Utopia (London: Thames and Hudson, 2020) p. 53.

Gregory Claeys, Dystopia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017) p. 5.

Robert R. Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005) p. vii.

Claeys, Dystopia, p. 120.

Simon Schama, Citizens (New York: Random House, 1989) pp. 630 and 619 – 639 passim. And see Google AI when searched for “Holocaust for Liberty.”

Schama, Citizens, p. 618.

Dante Alighieri, Inferno,(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989) p. 25.

Nadezhda MANDELSTAM, Hope Abandoned (New York: Athaneum, 1974)

Claeys, Dystopia, pp. 146-154.

Claeys, Dystopia, p. 147.

Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon (New York: Scribner, 2019)

George Orwell, 1984 (Pomodoro Books Online Edition, 2020)

Orwell, 1984, p. 3.

Claeys, Dystopia, p. 415.

Orwell, 1984, p. 55.

Orwell, 1984, pp. 54-55.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/24/iran-strikes-nuclear-sites-report

www.youtube.com/watch?v=70NgaziutAA

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jun/26/trump-intelligence-iran-iraq-wmd-analysis

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/jun/26/trump-intelligence-iran-iraq-wmd-analysis

Your Local Epidemiologist <yourlocalepidemiologist@substack.com>, June 26, 2025.

To me…”ignorance is strength!!!”

What stands out t